Some years ago I attended an evening of mime by Marcel Marceau, an elaborate exercise in aesthetic purification during which the audience kept applauding its own appreciation of culture and beauty, i.e., every time they thought they recognized what was supposed to be going on.

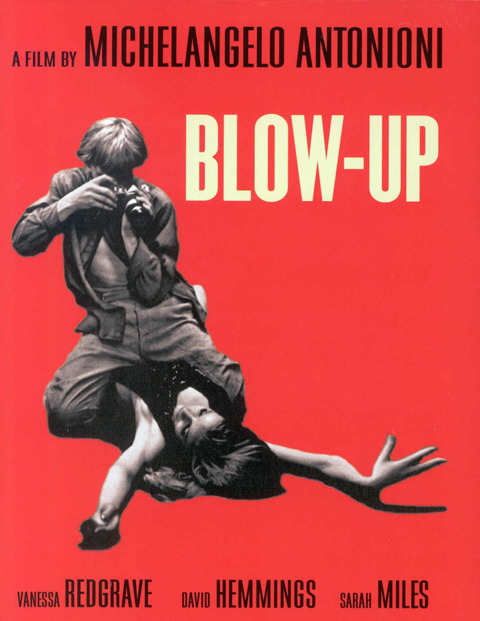

So begins Pauline Kael’s Tourist in the City of Youth – a comprehensive take-down of the circus of bullshit in, and in the wake of, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up. Published in The New Republic in 1967, it’s a thrilling, bracing read, swinging from one exquisite demolition to the next.

She nails the hypocrisy of “highbrow” art’s seeming disdain for pop culture while simultaneously drawing strength and vitality from it. I adore her reminder that, for all the easy moralizing, the frisky, colorful, grass infused Mod scene the movie depicts seems, if not harmless, more than a little, um… fun… A big chunk of the essay dismantles the cheap profundity of lazy symbols, easy targets, and disingenuous critics:

People seem awfully eager to abandon sense and perspective and humor and put on the newest fashion in hair shirts; New York critics who are just settling into their upper-East Side apartments write as if they’re leaving for a monastery in the morning… a surprising lot of people seem willing to accept assumptions such as: the fashion photographer is symbolic of life in our society and time; he turns to easy sex because his life and ours is empty, etc. Mightn’t people like easy sex even if their lives were reasonably full? And is sex necessarily empty just because the people are strangers to each other, or is it just different? And what’s so terrible about fast, easy success? Don’t most of the people who cluck their condemnation wish they’d had it?

Aces, just aces. The whole thing is a masterpiece of dense, sharp, and admirably personal criticism, sure, but given its scope and depth it’s practically an aesthetic and cultural manifesto. She’s arguing, as always, for honesty and passion, yes – but what she’s really getting at, what she finds unforgivable, is the emotional distance, the “knowing” disconnection in both filmmakers and critics from their ostensible subject. “Love-hate is what makes drama not only exciting but possible,” and what she loathes, justly, is the lack of love.

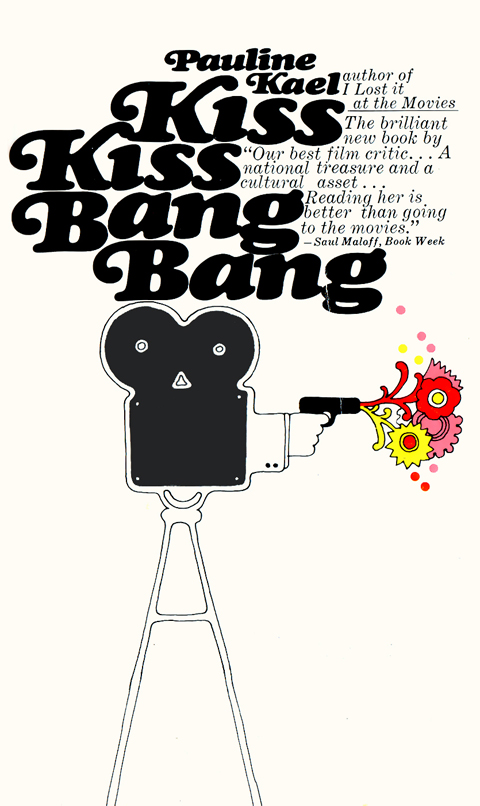

ABOVE: absolutely killer cover art for Kael’s perfectly titled 1968 collection of criticism, and the iconic poster for Blow Up (more on its graphic significance here.)