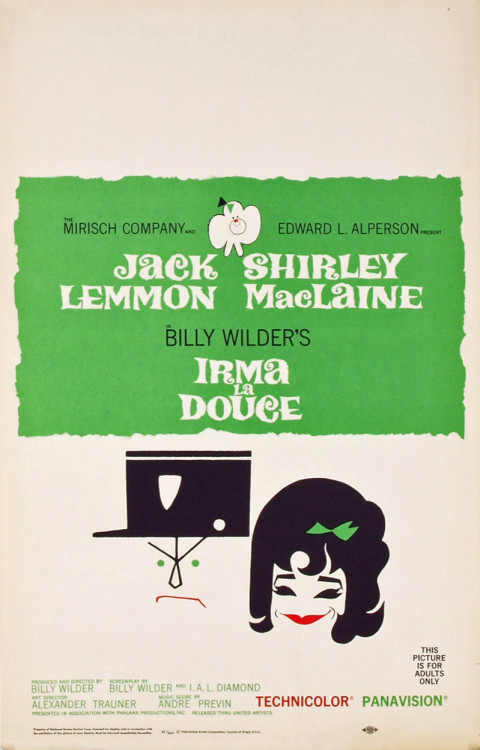

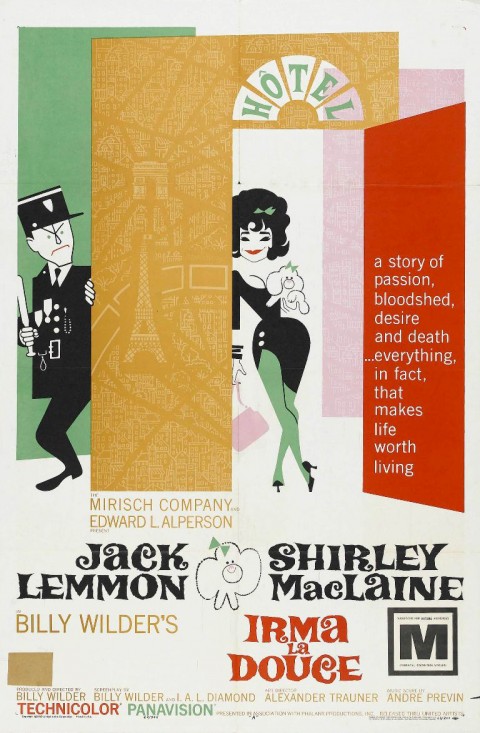

A selection of some fab posters for films by pioneering French director Claude Charbol, who died this week. (Some decent obits here, and here.) A giant of French cinema, Charbol was a founding member of the French New Wave, close pals with (and somewhat of a patron to) Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and Éric Rohmer. Along with Rohmer he published a seminal critical work on Alfred Hitchcock, a significant influence.

Charbol was often described in shorthand as the French Hitchcock, which is pretty dead on, adjusting a bit for time periods and sensibilities. While not strictly a formulaic filmmaker, diabolical plots, melodrama, all manner of decadence, wry humor and a general wickedness abound.

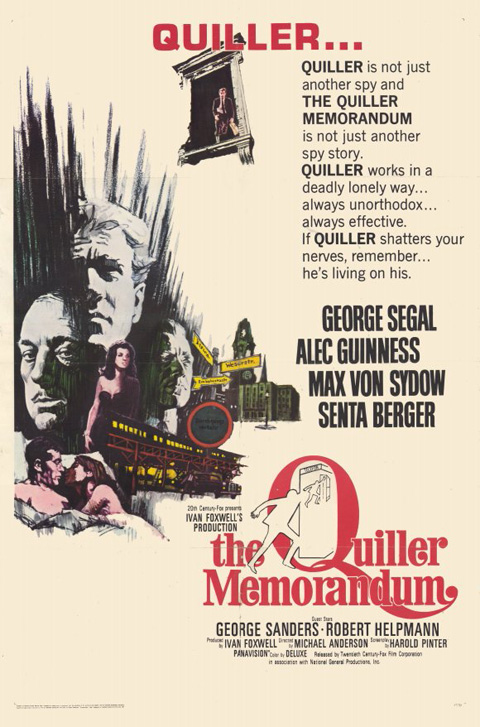

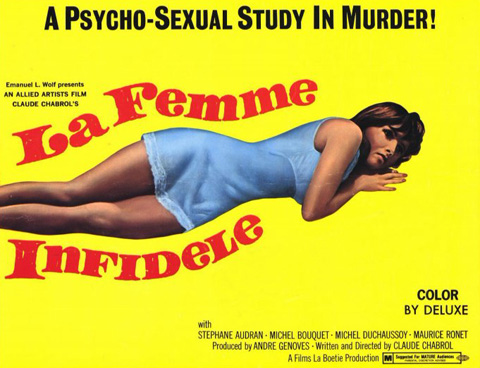

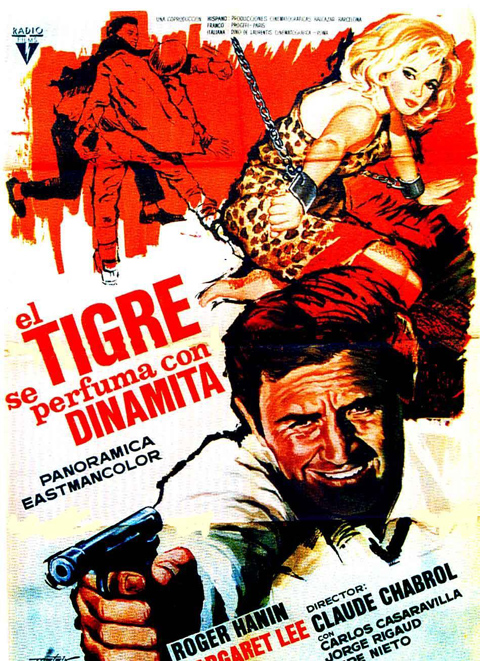

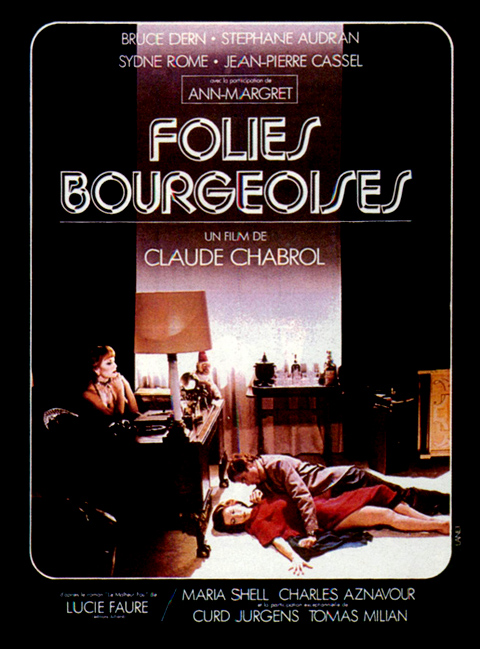

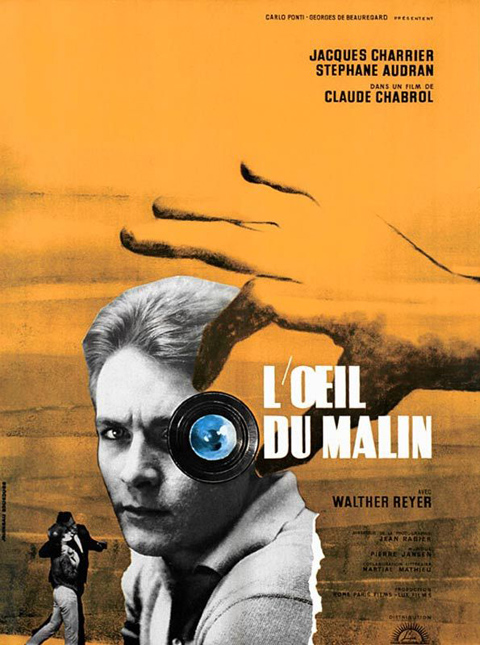

For your consideration, a passel of recommendations from his extensive oeuvre: A Double Tour, 1961 – a convoluted noir, Who’s Got the Black Box?, 1967 – shaggy, but entertaining espionage yarn, The Unfaithful Wife, 1969 and Innocents with Dirty Hands, 1975 two chilly, melodramatic physiological thrillers, Cop Au Vin, 1985, the first of two top drawer police procedurals featuring inspector Jean Lavardin, Masques, 1987 an intriguing character-driven mystery, The Swindle 1997, a neat little caper, Merci Pour Le Chocolat, 2000 about a wealthy family’s nest of secrets, and Comedy of Power, a corporate boardroom drama. Available here, or at your fine local video store.