1. Andrew Wyeth and John Updike seemed to have a preternatural communion with the fundamentals of their art. Updike apparently brokered a separate and special understanding with the English language. Wyeth seemingly could will individual bristles to do his bidding in a brutally unforgiving medium awash with chance and accident.

2. Both were, fundamentally, sophisticated traditionalists. Neither flinched from the progressive edge of their art. In fact both, for the sheer love of craft, frequently experimented beyond the comfortable boundaries of their mastered style. As a result they were able to continually infuse their renderings with a freshness and modernity that kept their work free of a willfully grumpy stodginess.

3. Their aesthetic sensibilities were rooted in the landscape of rural Pennsylvania. In my own noggin, there is a direct and immediate shortcut from Updike’s descriptions of the sandstone farmhouse he grew up in Plowville to any number of Wyeth’s paintings.

4. Oddly, Updike initially set out to be an artist and graphic illustrator. He attended The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art in London. It was in there and then that E.B. White offered him a position at The New Yorker, setting him on the path to becoming John Updike.

5. Wyeth, it seems, could easily have been an invention of Updike’s. His frail, sickly boyhood could have been inspired by a mix of Updike’s own rural upbringing and with his youthful artistic aspirations. Wyeth’s father, the legendary and formidable illustrator NC Wyeth, embodied pure and lusty storytelling, as well as the heady days of classic newspaper and magazine illustration that Updike so clearly adores. Wyeth’s long, determined dedication to an unwavering artistic vision as the fads and movements of the art world swirl around him make of him a Rabbit Angstrom like barometer, taking the measure of a changing culture. Even the ill fated Helga escapade feel more palpable as a fictional gambit. As Updike puts it in the beginning of his review of the Helga exhibit, “What do you do with the girl next door?” With that one sentence he hauls the entire affair under the purview of his great obsessions. The secret studio sittings, the bracingly lusty implications of the poses, the vectors of adultery and faithfulness, the complex role of Wyeth’s wife, it all feels of a piece with Updike’s milieu. To think what Updike would havr done with the evocative contradictions and elegiac beauty of the scene depicted in one of Wyeth’s last paintings… The sleek, cream and burgundy wood interior of the artist’s private plane, a woman in a immaculate, white, elegant coat staring through the window down at a gritty farmhouse, a tiny toy miniature of the world that Wyeth spent a lifetime mapping in exquisite and painstaking expressive detail.

6. Both men were targets for a certain smarty pants critical set. In the long view, arguments about the “merit” of representational realist vs. abstract art seems rather, um, “academic” and has everything to do with personal aesthetic and ideological affinities and toss-all to do with any external objective measure. Both had their trouser cuffs perpetually nipped by hipster accusations of a certain snobbishness and squareness. Measured against the accumulated bodies of work, how small and prune-faced the given griefs seem!

7. That said, both reputations accumulated scuffs and dings. Wyeth stumbled badly in the gauche hype he whipped up for the Helga paintings, needlessly overshadowing what was simply a worthy addition to his oeuvre. As for Updike, while his essays and the occasional short stories remained sharp and well turned, in his latter years he slipped from the height of his craft. Reviews settled into a predictable, dispiriting series of polite, genial soufflés that inflated what was in essence a consistent three letter critical verdict: “meh.”

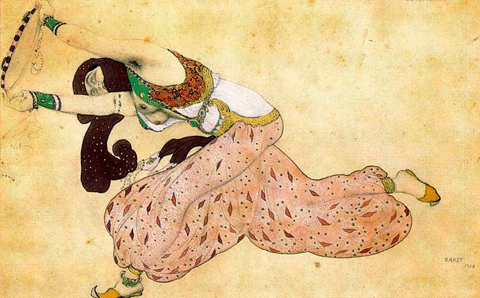

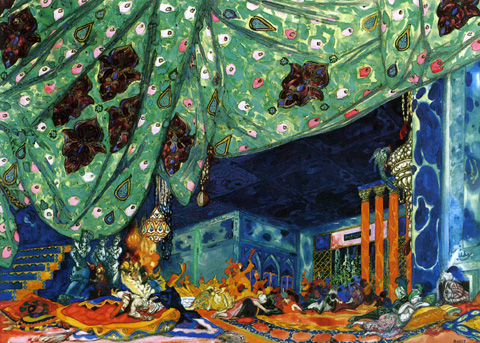

8. Updike was an unaffected and perceptive enthusiast of the visual arts. Unsurprisingly, his writing on art is beautifully descriptive, insightful and free of larded cant. In his review of the Wyeth’s Helga paintings he observes that the roughly painted swathes of hatched backgrounds, while surely evocative of the high art abstractions of Franz Kline, are just as suggestive of the background techniques of the great commercial magazine illustrators like Al Parker and Jon Whitcomb. He goes on to suggests that Wyeth’s close comfort with the illustrative tradition helps account for his critical ostracism. Updike, an enthusiast of the American vernacular, is rightly untroubled by the inevitable promiscuous interplay between commercial and fine art.

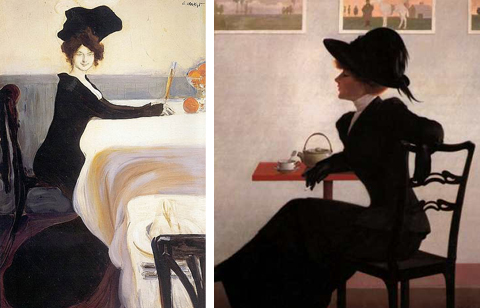

9. Last year the National Endowment for the Humanities invited Updike to present the Jefferson Lecture, the government’s highest humanities honor. Updike’s lecture was entitled “The Clarity of Things: What Is American about American Art.” It is well, well worth reading. He concludes, fundamentally, that ” The American artist, first born into a continent without museums and art schools, took Nature as his only instructor, and things as his principle study. [He developed] a bias toward the empirical, toward the evidential object in the numinous fullness of its being” Updike builds to that conclusion with a nimble and catholic survey of 200 years of American art, and weaves this common tread to bind together earnest Copley, creamy Sargent and stern Sheeler, arch Warhol and jazzy Pollack. We are all, realists, really.

10. A last convergence. Wyeth often worked in egg tempera, which involves hand-grinding dry powdered pigments into egg yolk. As I was thinking about the exacting preparation and application, it struck me that it served as an unusually apt metaphor for Updike’s prose – Sharp, rich specific details suspended in a flowing medium which quickly hardens, fixing the scene in enameled perpetuity.

(a note: These ruminations are heavily indebted to Lawrence Weschler’s convergences – essays that explore connections and resonances between disparate images or ideas. His amazing and beautifully designed collection, Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences, can be bought here.)