…Across the province of Ontario, which I call home, Queens Highway no 17 plies for some 1000 miles through the pre-Cambrian rock of the Canadian Shield. With its east/west course deflected, where it climbs the northeast shore of Lake Superior, it appears in cartographic profile like one of those prehistoric airborne monsters which Hollywood promoted to star status in such late late show spine tinglers of the 1950s as Blood Beast From Outer Space or Beak From Beyond, and to which the fuselage design of the XB15 paid the tribute of science borrowing from art…

So begins, improbably, the narration of “The Search for Petula Clark,” one of a series of radio features the classical pianist Glenn Gould made for the CBC in the late 60’s, after his abrupt retirement from public performance. Gould’s story is often understood in terms of the standard drama of eccentric genius: young and brilliant, and yet temperamental and odd, he burned bright, was subsumed by his eccentricities, faded out, cue credits, etc. To regard Gould as the Howard Hughes of classical music may be romantic, but it obscures far more interesting motivations that led him to abandon the concert hall at the peak of his career. The radio documentaries provide not only a key to understanding Gould’s decision, but an inspiration to anyone who finds aesthetic and intellectual pleasure in the unlikeliest of places.

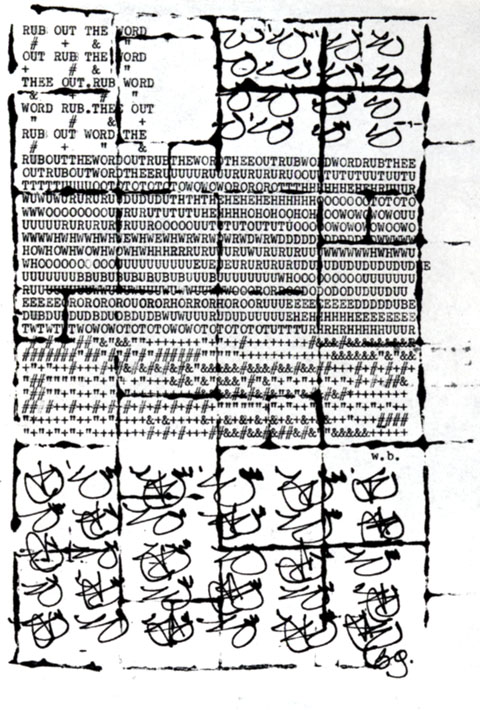

Described by Gould as “Contrapuntal Radio,” the documentaries were exquisite sonic constructions, built of precisely calibrated layers of voices and under-girded by a lattice of sound effects and musical passages. They were explicitly musical. Gould composed fugues of dialogue that cumulatively evoked notions greater than any of the individual sentiments themselves — like chords of language and thought. Each is narrated in Gould’s distinct voice–complete, rounded pronunciations of each word, formed without dropped syllables. Full word follows full word, separated by a crucial, clean, split second of silence in a quick, steady, hypnotic cadence.

Both in ambition and the complexity of construction, “The Search for Petula Clark” is probably the simplest of his radio features. However, it serves as a great precis of the main themes that animate Gould’s major radio works like “The Idea of North,” about the effects of living in solitude; “The Latecomers,” about Newfoundland; and profiles of composers Leopold Stokowski and Richard Strauss. One way or another they involve the discovery of deep aesthetic pleasures in the everyday, the fundamental character of ideas, and the mechanics of creativity.

As the “The Search for Petula Clark” continues, Gould drives through the remote regions of northern Canada, listening to the radio. As he passes from town to town, he compares naming conventions (Michipicoten, Jackfish, Terrace Bay) to describe three generations of settlers that have defined the region’s history. A passing observation of local real estate stratification unlocks the complex interplay of social standing, industry and the limits of upward mobility. As he heads once again into the wilderness, he sees the first of an array of relay antennae that pass radio signal deep into the endless stretches of the north. Utterly captivating, this is just Gould clearing his throat; acutely aware of cinematic staging, his introduction begins with an establishing aerial vantage, swoops down, passes over the landscape and under the wires, and pulls back up as the opening measures of Petula Clark’s “Sign of the Times” fade in and his ruminations begin.

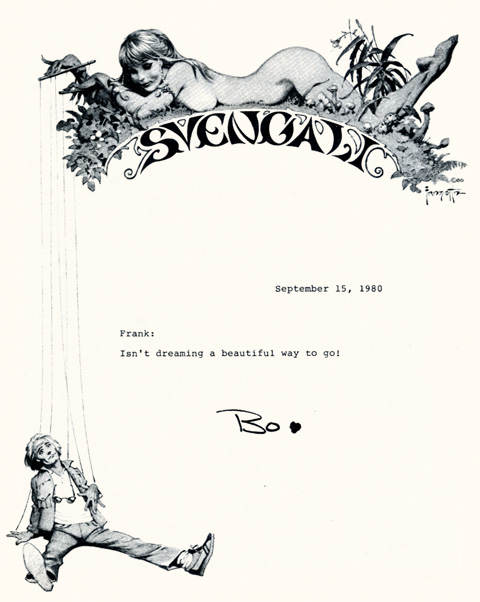

Goodness gracious, how this cat riffs! Based on a close reading of four consecutive Clark singles (“Downtown,” “Sign of the Times,” “My Love,” and “Who Am I?”), he constructs a loose, yet full-field, theory on the distinct stages of mid-century pop stardom and sketches a pocket biography of Clark. He fuses Clark’s four singles into a coherent melodramatic arc: youthful earnestness, hope, urban vitality, romantic disillusionment, culminating in the “tenor of mindless confidence and the tone of slurred articulation… the interminable mid morning coffee hour laments of all the secret sippers of suburbia”

Along the way, Gould pauses for a hilarious, brainy and impertinent digression on the Beatles. With a sophisticated, yet idiosyncratic, musical analysis, he indicts the group as hopped-up folkie barbarians, rube minstrels filling an ageless role in cooking up a good racket. Yes, yes, so far, predictable fogey fare. Then comes a lavish testimonial to the acumen of Clark’s composing partner, Tony Hatch, remembered now mostly as a cheesy 70’s TV soundtrack hack, but once a deft and felicitous pop composer and early-60’s collaborator with Scott Walker and David Bowie. (As a prescription, Gould’s vision for popular music essentially endorses the approach embodied by decadent french pop maestro Serge Gainsbourg, especially in his magnum opus “Melody Nelson”–thoughtful orchestrations, found sound, collage, spoken word passages and soap operatic drama.)

Besides their intrinsic interest, the relevance of the radio documentaries lie in their restless curiosity. Sometimes it seems as if Gould is interviewing reality itself. They are driven by a passion to illuminate the deep worth of overlooked things. Art could be anywhere; you had to tease it out, as he put it, by keeping “all the elements in a constant state of flux, interplay, nervous agitation, so that one is buoyed aloft by the structure.”

This notion serves as a manifesto of sorts for Gould. He spent his life soaking in the details of the world around him, observing, making, tuning, recording, tweaking, sketching, musing, opining, composing. To enter into Gould’s world is not to part the curtain on a reclusive eccentric. His abandonment of performance and his subsequent work are best understood as a commitment to a life of ecstatic appreciation. It’s what makes him practically a patron saint to passionate enthusiasts. Gould devoted himself to the central preoccupation of any cultural omnivore: the development of a self sustaining aesthetic universe, with consistent rules and endlessly roiling passions, full of quirks, strangeness, and charm.