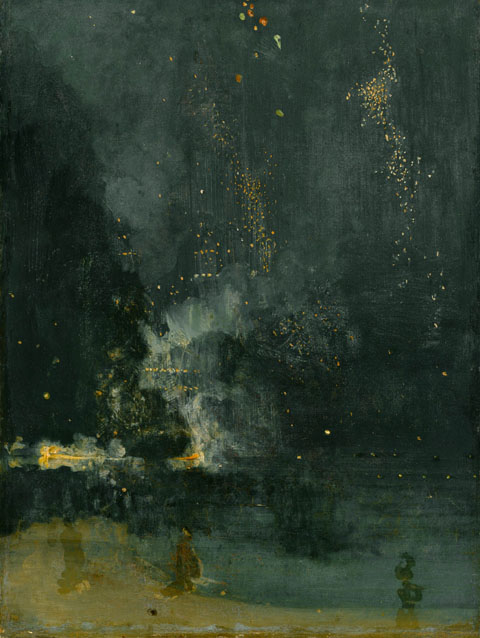

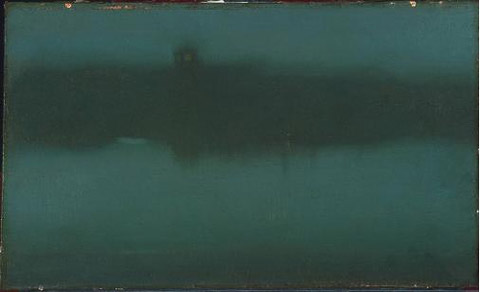

I love the dynamics of things caught in the balance between representation and abstraction – the way recognition, whether visual or melodic, phases in and out of focus. It’s why I’m so taken with the series of Nocturnes by James McNeill Whistler. Painted from memory, composed as “impressions,” they function as little ambient pocket movies, with details and forms taking shape and then submerging again as your attention wanders.

Cool cat, too, this Whistler, fervently devoted to beauty, art for it’s own sake, lusty bohemianism, etc., and produced a beautiful, quirky and singular body of work. Prescient as well – his linkages of art to music, representation to abstraction, and incorporation of chance and accident where strikingly modern. Furthermore, his cranky confidence in the value of his work in the face of critical dismissal led to one of the great kerfuffles of art history. Whistler sued the critic John Ruskin for remarking, upon seeing Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, “I have seen, and heard, much of cockney impudence before now; but never expected a coxcomb to ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face” (Coxcomb! there’s one to remember – a conceited, foolish dandy or pretentious fop. Its synonyms are equally wonderful – popinjay and jackanapes.) More on the trial here.

Above: Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1874), Nocturne Grey and Gold Snow, Nocturne: Grey and Gold – Westminster Bridge (1871), Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremorne Lights (1872), Nocturne (1875)