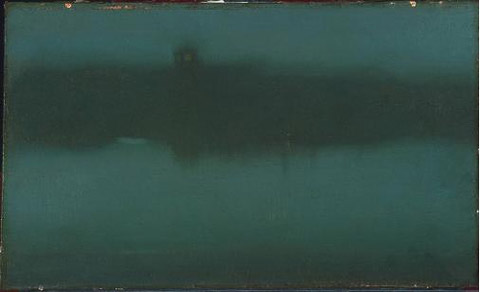

I recently took a pal to the Isabella Garder Museum in Boston. It is simply one of the most beautiful, sublime environments to take in art — it’s an indelible reminder of how central decor & architecture are to the experience of a particular artwork. That experience is especially powerful and acute in the famous “Yellow” and “Blue” rooms, where furniture, small doodles, ephemera, exquisite wallpapers, surround and mingle with masterworks by Rossetti, Sargent, Whistler and Degas.

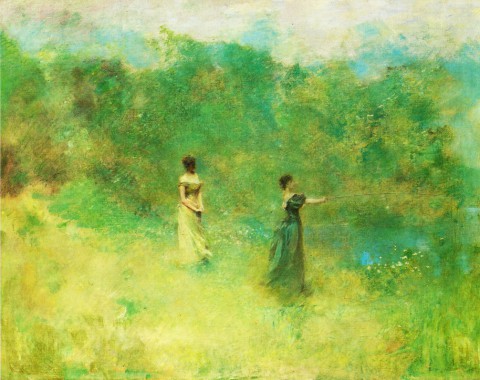

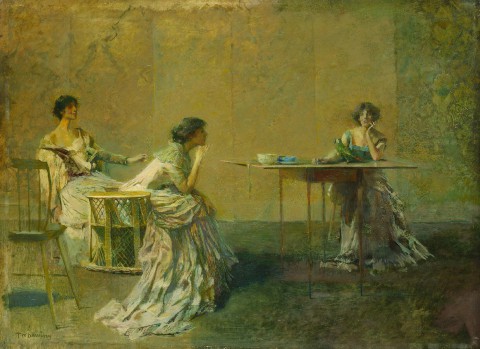

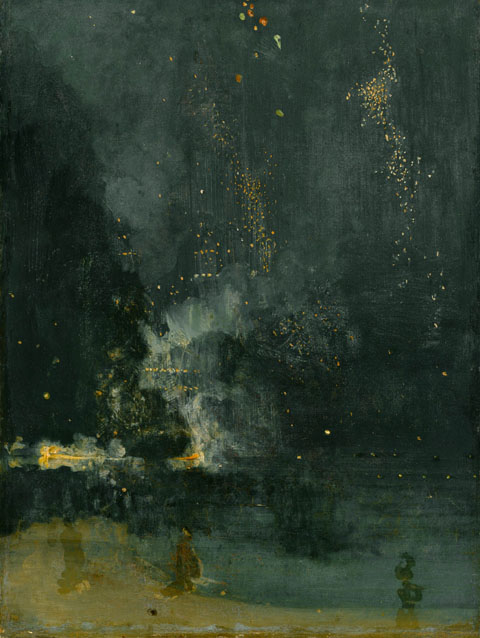

My collegue was particulary taken with a smallish, glittering portrait of a woman (above) by Thomas Wilmer Dewing. Further research hauled up a lovely cache of paintings — most stranger & more fetching than the one in the Gardner. Turns out Dewing was a tonal painter heavily influenced by James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s work, especially his famous Nocturnes (which I also dig. I wrote about them a few years back, here. There’s also one in the Yellow Room) There’s a gauzy texture to his paintings I absolutely adore & sets them well apart from the usual parade of society portraiture and pastoral vingettes. Enjoy.