Always shave after a hot shower. Always begin with a hot towel. Cream. Gel. Stick with Gillette. Go with Schick. You can always trust a Remington. Williams Rose Soap, Dr. Harris Arlington Shave Stick, or Bigelow Shave Cream? Shave at night. Always rinse the blade between strokes. Pat (don’t rub!) dry. Nothing but Aqua Velva. Always finish with a splash of Witch Hazel.

One of my most cherished photographs is of my grandfather shaving while I gaze up at him intently, mimicking his gestures. Whenever I linger on it, I feel the weight of that moment – but it is a good, simple weight, an uncomplicated weight. And sometimes I feel the distinct sensation, not unlike a film reversing at great speed, of things folding in and winding back to their source.

Shaving is dense with meaning. Its result is nakedly public, its practice intensely private. It’s informed by lore, oral tradition, loyalty, filial bonds, gear, principle, aesthetics, and technique. Woven into it is the obligation to pass it down to the next generation, whether as fathers, uncles, or brothers. We do it, carefully, regularly, for ourselves, and for each other – in particular for loved ones, but more broadly for everyone we might encounter – a small adjustment on behalf of society, even civilization.

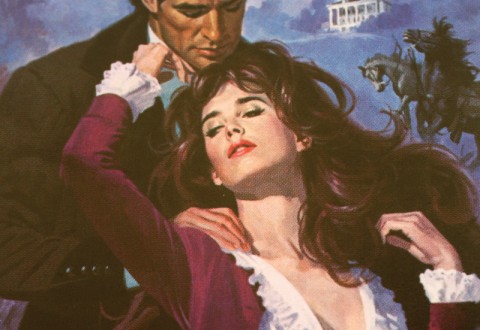

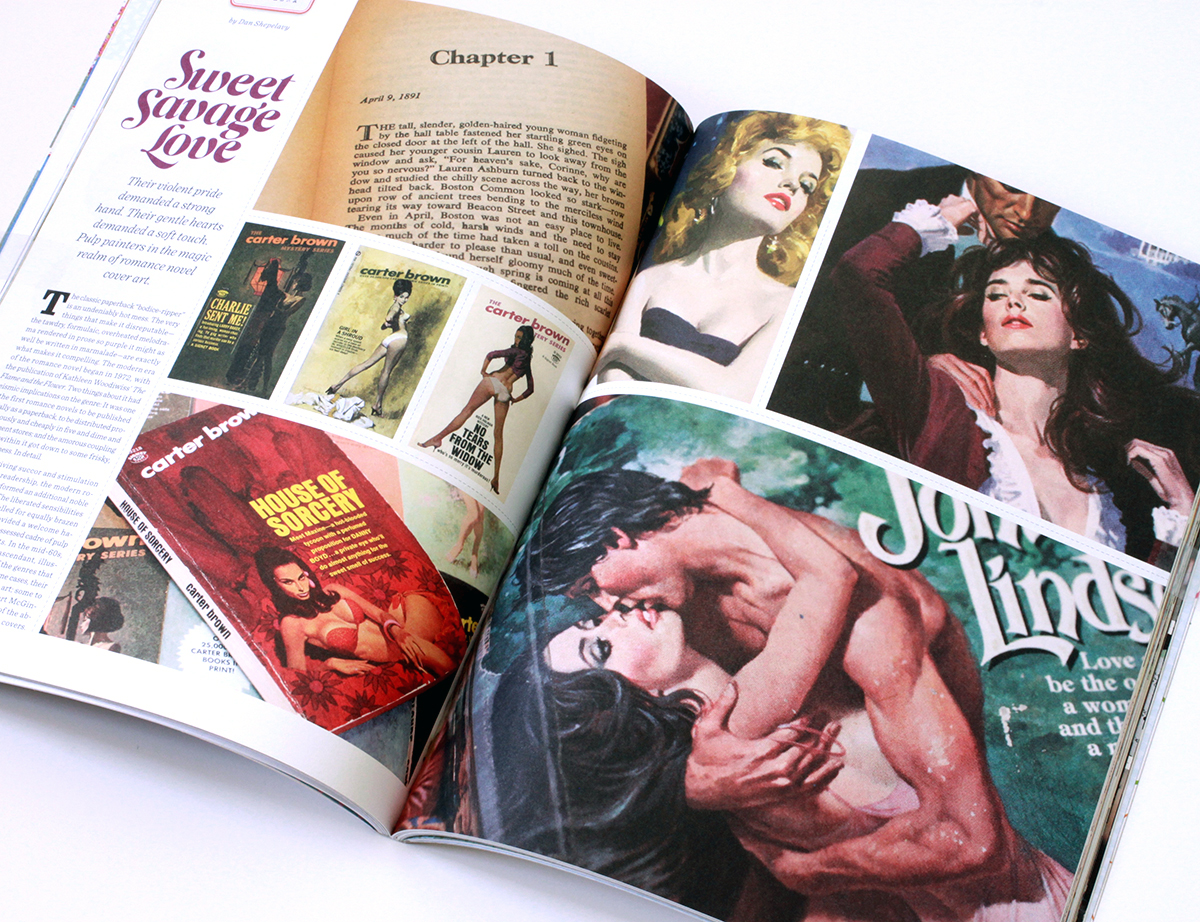

Shaving may be the most effective shorthand for masculinity itself. Take, as a particularly vivid example, the March 1965 cover of Esquire magazine. It was designed by the legendary George Lois, who, among his many gifts, showed an unerring instinct for the provocative and iconic visual metaphor. For a story on the masculinization of the American female, he slathered a thick beard of shaving cream on the fetching Virna Lisi, and in doing so created an indelible image of simple, enduring impact. It triggers uncannily primal impressions, simultaneously sexy and unsettling, brash and subtle. Lois himself recognized its power – he chose it again for the cover of his manifesto, The Big Idea.

There are four great eras of shaving, defined by the implements themselves – the straight razor, the safety razor, the electric razor, and the self contained cartridge.

The straight razor era is truly paleolithic, extending from 3000BC, with the development of copper razors by the Egyptians. Wielding and caring for a straight razor requires considerable finesse. Precise handling is crucial, with the potential for a nasty nick or gouge ever present. Maintaining the sharpness is equally difficult, requiring swiping the blade across a thick leather swatch, or strop, and at a particular angle and pressure. Whereas it was once a necessary skill, today it is the province of the rarefied expert. Its allure remains strong, however, and persists as a benchmark of the ultimate shave.

The safety razor, on the other hand, is no less than a signal achievement of the industrialized age, fulfilling the democratizing promise of mass production. It was initially invented in the 19th century by a Frenchman, Jean-Jacques Perret. In 1904, United States Patent #775,134 was granted to King C. Gillette for his version. During the first world war, Gillette cut a deal with the US military to be the exclusive supplier of this radical new convenience; by the end of the conflict, practically the entire nation had been converted to this new format.

The safety razor’s distinctive silhouette has remained basically unchanged since its invention. It is a truly beautiful thing – a thin wafer of machined metal, with a barbell shaped cutout playing a sawtooth rhythm off an a straight edge. Even its very physicality is compelling; utterly rigid while braced in the shaver, yet supple and yielding in the hand. It’s also wonderfully universal, a common unit around which springs competition and innovation, never splintering into hermetic zones of incompatibility. One’s new fangled handle will accommodate another’s new and improved blade. It’s an open source dynamic.

In scontrast, the advent of the electric shaver is no less than the big lie – a dark worm eating away at the bargain of faith we make with commercial culture. Because, while we allow ourselves to be shamelessly flattered and seduced, we expect basic satisfaction. Which is why the phrase, “Shaves as close as a blade or your money back” is a statement of purest evil. It’s simply not true. At all. And backed by a guarantee, no less. The gap between promise and performance is so great, so wide, that it should disqualify the entire enterprise. But no – since an opening fusillade of advertising during the wiz-bang atomic age, every few years some bogus technological advance is trumpeted with the same insulting result. After ineffectively pulling, thwaking and hacking away willy-nilly, you’re left with a desolate landscape of miniature prickly stumps. Feh.

Since the late ‘70s, a series of diverse, proprietary cartridge technologies have emerged, competing against one another. As with much of today’s consumer culture, there are some high points, amidst much junk and the constant whiff of cheapness and compromise.

One particular triumph was the Gillette Sensor, the first razor with twin blades individually mounted on highly responsive springs. Invented in 1990, the Sensor significantly enhanced the quality of the basic shave. It was also an genuinely well designed and handsome implement, as solid as anything you could hope for in this era of injection-mold flimsiness. Sadly, Gillette has been at a loss for a followup ever since. A series of mostly minor tweaks to the Sensor gave way to an obnoxious series of tricked out shavers – the Mach 3, the Mach 3 Turbo, and the absurd five blade Fusion, Fusion Power and Fusion Phantom.

Like Gillette, nearly the whole industry seems hostage not only to the super-sizing ethos, but to the notion that the only meaningful reference points remaining for men are an aggro mashup of x-treme sports and technology. The men’s toiletries aisle at any drugstore is a strip-mall of exploded ESPN graphics – random jagged shapes, glowing swooshes, and chrome extruded type. In the midst of this gale force dude-ness, however, a few brands stand proudly apart, buoys anchored to broader taste as well as shaving’s classic past.

The beloved Barbasol can, still a reliable mainstay in any old-school barbershop, retains its midcentury-modern look – pop color bands and pinstripes that evoke a classic barber pole along with a distant echo of the classic PanAm logo. Barbasol, a portmanteau word of “barber” and “solution,” was invented in 1919, when MIT professor Frank Shields created a shaving cream that did not need to be whipped into a lather. The brand was distinguished in the ‘40s and ‘50s by delightfully frisky ad campaigns with classic good-girl illustrations by E. Simms Campbell and Carl Setterberg, featuring fetching cutie after fetching cutie testifying to the allure of the “Barbasol” face. It grew quickly and steadily over the years until it became the leading brand of shaving cream in the United States.

The dandy at the party is surely the Clubman line by Penaud – distinguished by its filigreed label, gold, green and red color scheme and top-hatted gentleman leaning nonchalantly on his cane. Founded in France in 1810, it broke into the American market in 1920 and quickly

established itself as a connoisseur’s brand. James Bond preferred it, as did Cary Grant and Robert Mitchum. The 1970s were a brutal period for Penaud, its hold slipping under wave after wave of budget colognes and aftershaves like Aqua Velva, English Leather, Jaguar, Hai Karate, and Brut. It was sold off in 1990 and re-formulated. Happily though, the quality of the Clubman line was unaffected, and today it enjoys the same comfortable niche existence it always had with wet-shaving enthusiasts, country clubs, and classic barbershops.

To shave is to declare yourself. You step into subtle cohorts, you join proud ranks. A close trim, a clean shave, a lopping off of sideburns, ratifies your place in the middle current, the rushing mainstream. Lowering the sideburns extends a hand towards Bohemia. Growing a beard is a de rigueur passport to many subcultures – the fussy pride of young hipsters, the venerable tribe of gay “bears,” or the swarthy ranks of bikers, to name just a few. As a signifier the mustache is profoundly versatile; it can be flamboyant, hopelessly retro, or positively conservative. Just consider, simultaneously, John Waters, Tom Selleck, and Ned Flanders.

How you shave also matters. It is a powerful clue to your philosophy, your default position. To embrace gel over cream is to venerate the latest convenience or gizmo, an explicit rejection of any nostalgic sentimentally. To shave electrically is to suggest an impatience with grooming itself – a waste of time and perhaps suspiciously indulgent. The committed wet-shaver is the hardcore hobbyist, close cousin of the Ham radio buff or the garage brewer, subsumed in the minutia of the craft.

In my case, I’m primarily a Gillette Sensor man. I do own a sturdy, vintage Merkur safety razor, but so far it lays mostly dormant on the vanity. Every now and then, though, I get a straight shave at John’s Barbershop in South Philadelphia. In operation since 1932, it’s a neighborhood legend, frequented, as an old newsman put it, by “surgeons and cardsharks; musicians and moochers; politicians and pool hustlers,” as well as golden age entertainers like Jerry Vale, Joey Bishop, Jimmy Durante and Robert Goulet. While its heyday may have faded, the experience that secured its reputation continues to flourish today.

As you settle into the supple leather of a vintage Belmont chair, your face is immediately enveloped in a thick, hot, wet towel. Once your whiskers have started to soften, the barber gradually works in a machine-mixed hot cream. Then he opens the razor, anchors the hinge in his palms, and – half surgeon, half sculptor – begins.

A straight shave is a dense array of little expert gestures, pulling taught and flicking, or passing along your contours in a smooth arc. Where modern shaving makes you think of your face as an upside down egg, a straight shave makes you aware of the subtlety of its construction. The barber expertly negotiates a latticework of planes, curves, and facets.

Unlike the bantering semi-alertness of a haircut, you surrender to a straight shave. You pick up snippets of conversation here and there – neighborhood bulletins and updates, a little crime, dollops of philosophy. John is a maestro of the art of conversation, with a thoughtful familiarity with his customers, a genuinely warm appreciation of the particulars, all the while deftly blending multiple private conversations into a single public one.

Then, abruptly, it’s over. For a few seconds a sensation of rawness begins to bloom, extinguished immediately by a balm of cocoa butter, then invigorated with a bracing sting of lilac.

Text and photography by Dan Shepelavy