Saw this, reminded me of that. (Falling Dog by Malcolm Bucknall, 1994, Bonaparte Crossing the Alps by the Great Saint Bernard Pass, Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse after Jacques-Louis David, 1807)

Table of Contents: Art

Saw this, reminded me of that. (Falling Dog by Malcolm Bucknall, 1994, Bonaparte Crossing the Alps by the Great Saint Bernard Pass, Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse after Jacques-Louis David, 1807)

So, I imagine a gizmo consisting of a sheet of heavy paper underneath four pens – red, blue, yellow, and black – held in a lattice of yarns and pulleys that lead to a net of exquisitely sensitive rubber pads. The rubber pads line the inside of a wide brimmed cloth hat. The hat is on my daughter’s head, she is on her bed, holding her stuffed manta ray and riffing on her general enthusiasm for fish, mermaids, aquatic dinosaurs, etc… the pulses of her noggin are picked up by the rubber pads and transmitted down the yarn, tugging and pulling the pens across the paper and rendering a scene that looks exactly like this print by Baltimore illustrator Jaime Zollars.

Recent sketchbook page (bottom painting by Martin Kippenberger, a “dandyish, articulate, prodigiously prolific artist who loved controversy and confrontation and combined irreverence with a passion for art,” accordinding to this, here.)

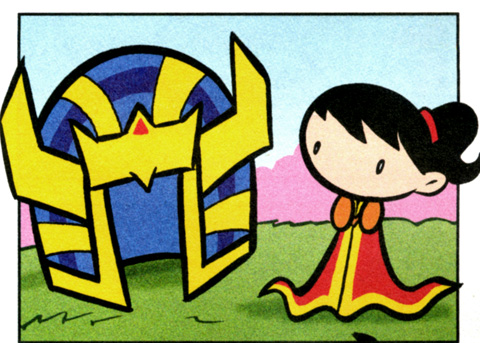

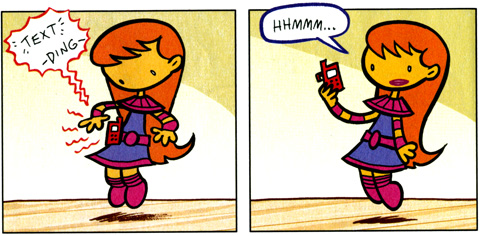

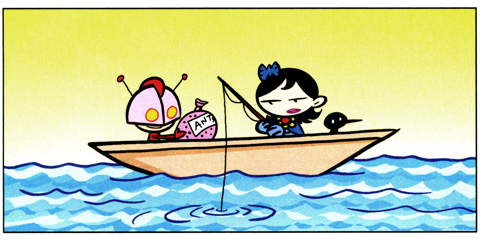

My daughter and I are both over the moon for Tiny Titans, DC Comics’ toddler takedown of their side-kick league. The graphic style is a note perfect blend of Jack Kirby’s blocky Biff! Bang! Pow! style and the emotive power and cuteness of Peanuts. The storytelling is a savvy remix of the source material – all the villains are reconfigured as hapless authority figures, all the adult superheroes as parents and guardians. The stories themselves are frothy little capers that squeakers will dig, with an additional level of meta commentary on the main DC universe for the nerds.

Master illustrator Frank Frazetta’s stationary design for addlepatted sun children Bo and John Derek’s movie production company, Svengali. I was going to leave the commentary at that, but I was riding my bike this afternoon, and the Walkman offered up Sheena, by Trader Horne, a long forgotten British psych-folk outfit. Hardly a stanza had passed when I realized the song was a tone poem to the idea of Bo Derek. I share it here, below, for your pleasure:

Sheena, Trader Horn:

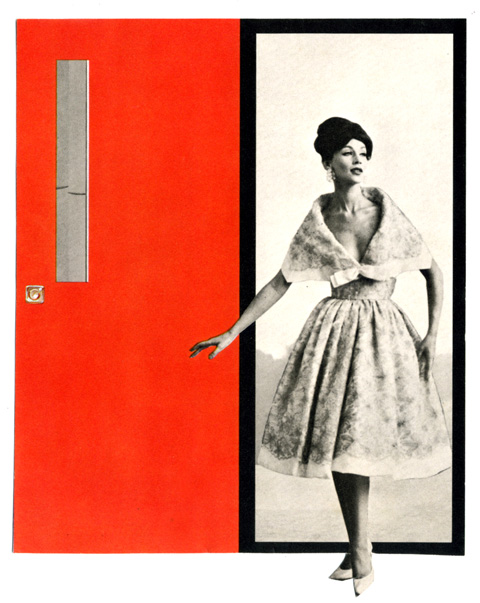

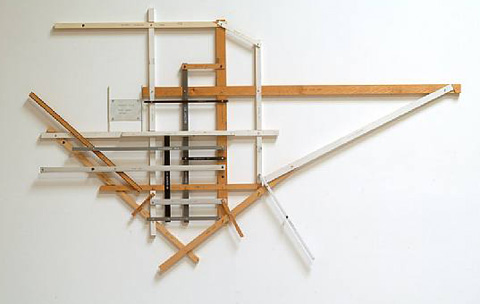

From the clipping files, a fab piece of found constructivism, courtesy of a late 50’s ad for a door manufacturer.

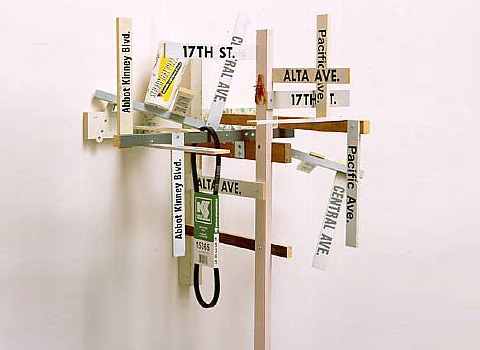

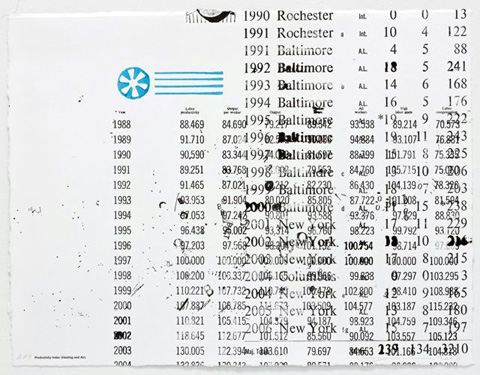

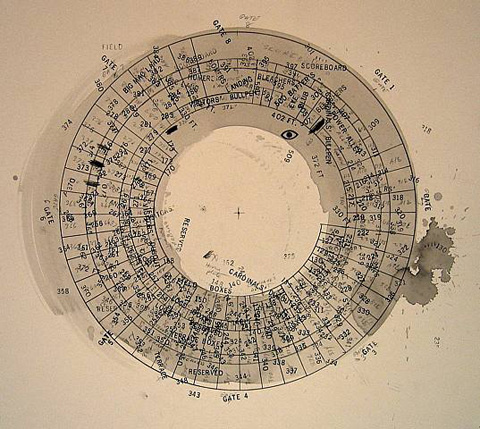

Inert and broken rulers measuring only their own lengths, street signs so densely clustered they tie the very idea of place into a thick knot, stadium diagrams and timetables rotated and overprinted until they blur into unparsable eddies of information… at the heart of Greg Colson’s work lies a desire to scramble, smear, or re-frame the established order of things meant to communicate a sense of order. That all the work still emanates a steady signal of pure information imbues it with a bracing clarity, while the degree to which familiar information is scrambled accounts for it’s fascinating power. I discovered Colson’s work in a remaindered copy of Giuseppe Panza: Memories of a Collector. Panza was a fervent enthusiast of post WWII modern art and among the earliest collectors of Rauchenburg, Rothko, Kline, and Lichtenstein (and a foundational donor to the Los Angeles Contemporary Art Museum). The book abounds in seminal and lesser known works by the greats (his Franz Kline collection is definitive) as well as top shelf lesser known artists, like Colson. Huge score, still in print, available here.

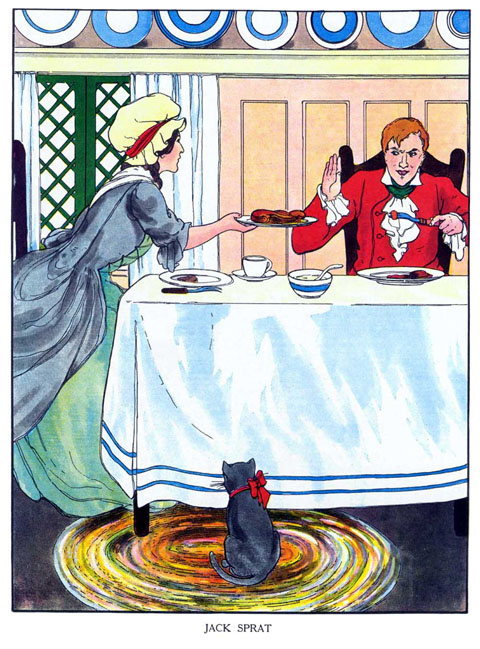

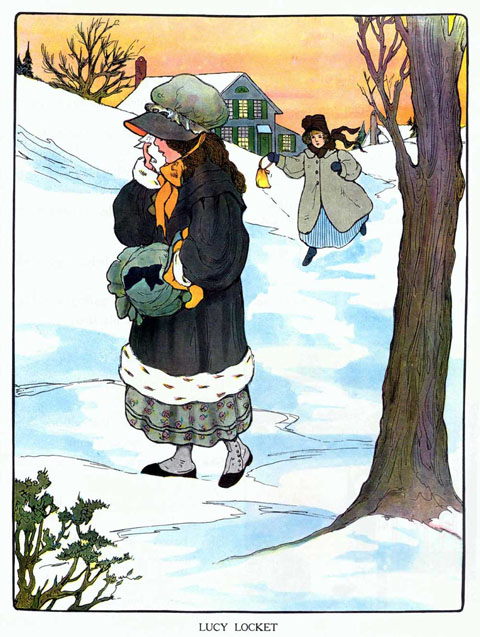

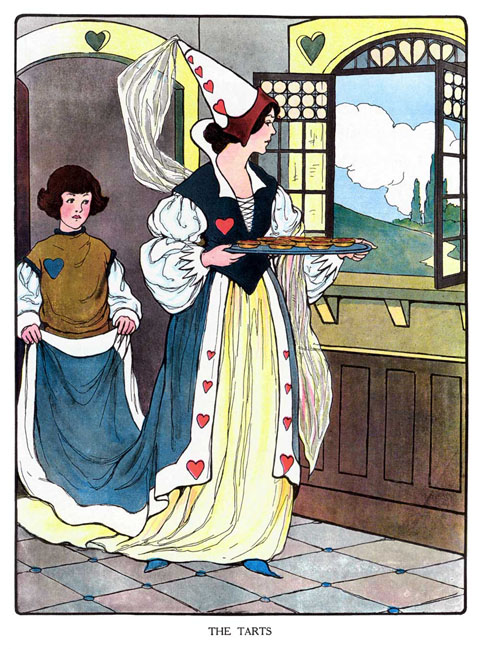

Edward Hopper, Summertime, 1943

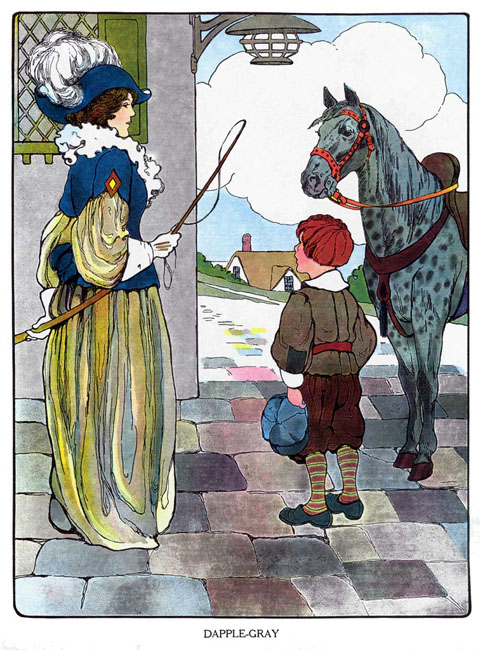

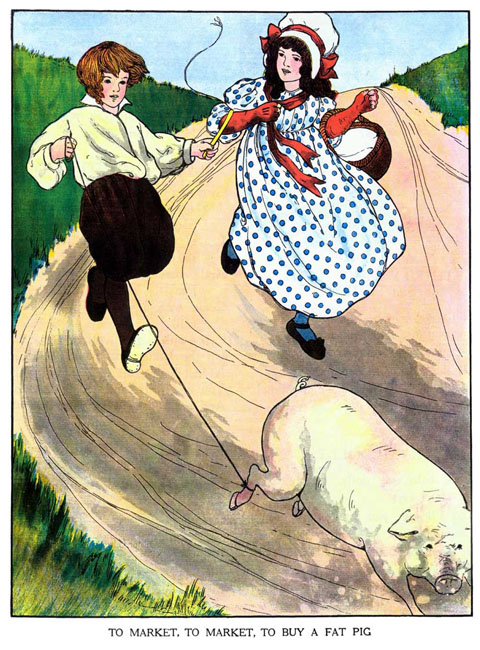

At this point, I read to my daughter from The Real Mother Goose mostly as an excuse to pour over the illustrations by Blanche Fisher Wright. Elegant and utterly charming, they sit shoulder to shoulder with the work of the great turn-of-the-century illustrators like Edward Penfield and Jesse Wilcox Smith (Philly’s own, Smith, born in Mt. Airy, studied at PAFA under Thomas Eakins and Howard Pyle at the Brandywine School) But what really captivates me about her work is the degree to which, stylistically, they recall the work of Art Nouveau http://www.health-canada-pharmacy.com masters like Alphons Mucha. They share the regal faces, flowing outlines, graphic crispness and posterlike composition. What transforms them into bewitching illustrations is her wonderful animating sense of gesture and flair for scene staging. Given her skill and achievement, her complete anonymity is surprising. Other than a few basic illustration credits, no biographical information exists online. She is absent from Walt Reed’s comprehensive Illustrator in America survey. Although The Real Mother Goose remains in print and easily available, Blanche Fisher Wright, at least for now, seems a near to complete mystery.

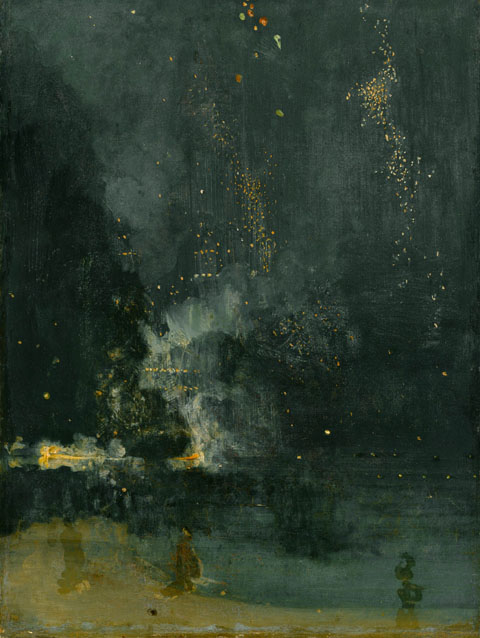

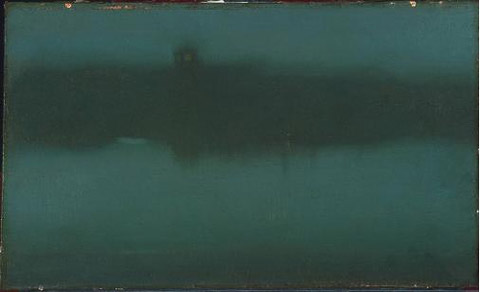

I love the dynamics of things caught in the balance between representation and abstraction – the way recognition, whether visual or melodic, phases in and out of focus. It’s why I’m so taken with the series of Nocturnes by James McNeill Whistler. Painted from memory, composed as “impressions,” they function as little ambient pocket movies, with details and forms taking shape and then submerging again as your attention wanders.

Cool cat, too, this Whistler, fervently devoted to beauty, art for it’s own sake, lusty bohemianism, etc., and produced a beautiful, quirky and singular body of work. Prescient as well – his linkages of art to music, representation to abstraction, and incorporation of chance and accident where strikingly modern. Furthermore, his cranky confidence in the value of his work in the face of critical dismissal led to one of the great kerfuffles of art history. Whistler sued the critic John Ruskin for remarking, upon seeing Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, “I have seen, and heard, much of cockney impudence before now; but never expected a coxcomb to ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face” (Coxcomb! there’s one to remember – a conceited, foolish dandy or pretentious fop. Its synonyms are equally wonderful – popinjay and jackanapes.) More on the trial here.

Above: Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1874), Nocturne Grey and Gold Snow, Nocturne: Grey and Gold – Westminster Bridge (1871), Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremorne Lights (1872), Nocturne (1875)

It took me a while to get past the sheer masterfulness of the technique to grok the lasting point of Eric Zener’s paintings. It’s the idea of water as a medium for human experience. It reduces us, isolates us, dwarfs us so profoundly that it coaxes from us our most fundamental expressions. To surrender to water is to shed complexity. Splashing, floating, leaping, submerging, basking, even walking along the ocean shore, are dense, but utterly basic, experiences. It’s that same kind of surrender that transforms this tightly focused series of paintings into something much more human and universal. Oh, and the technique is ridiculous. (On exhibit at Gallery Henoch, New York City, until May 9th.)

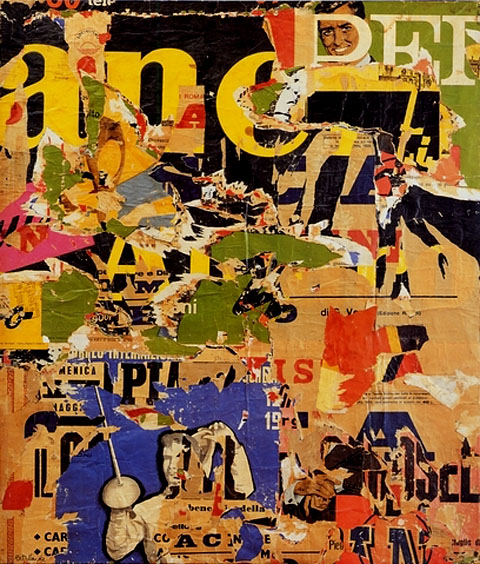

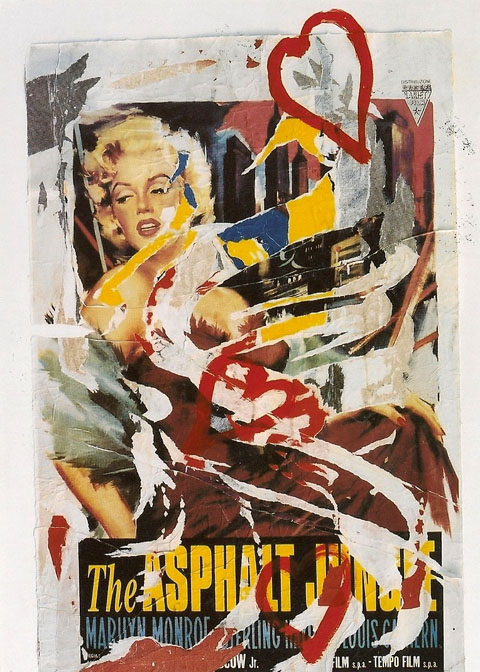

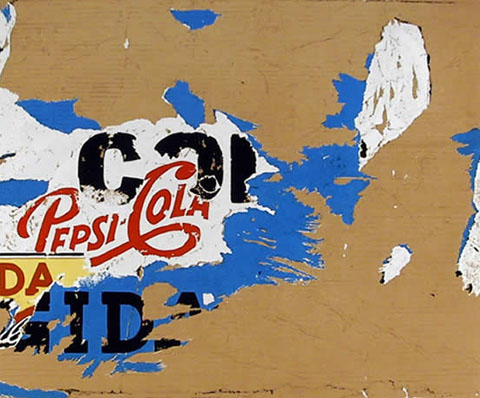

As with most great pop art, the pleasures of Mimmo Rotella’s decollages are simple ones – expressive technique, flashy subjects, and a lusty joie de vive. Rotella tore away at lurid, glamorous and melodramatic Italian ads and movie posters, ripping and chemically dissolving them into something essential. In each case what is revealed is a burst of pure expression: shards of glamour, rough tapestries of melodrama, and blurts of type. Although critical appreciations of his work are often barnacled with pomo foolishness, they lead to fascinating places. He was a member of a European variant of Pop art called Nouveau Réalisme, which was founded in Paris by Yves Klein. Related philosophically and aesthetically to the Dada and Fluxus movements, it will certainly be a subject of further research… (By the way, what is it with all the Italians around here lately? Boldini, Disco Volante, now Rotella, an upcoming post on Virna Lisi…)

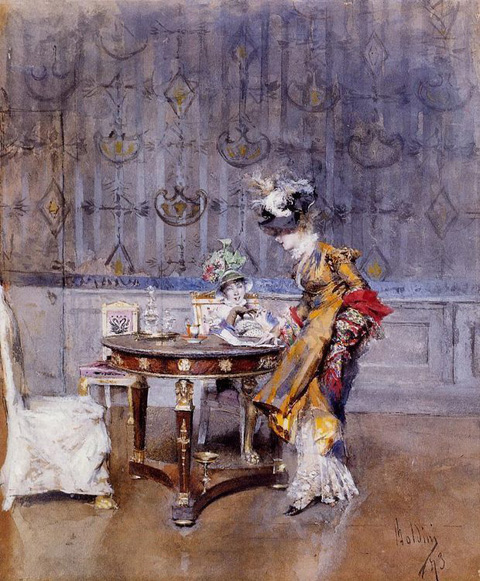

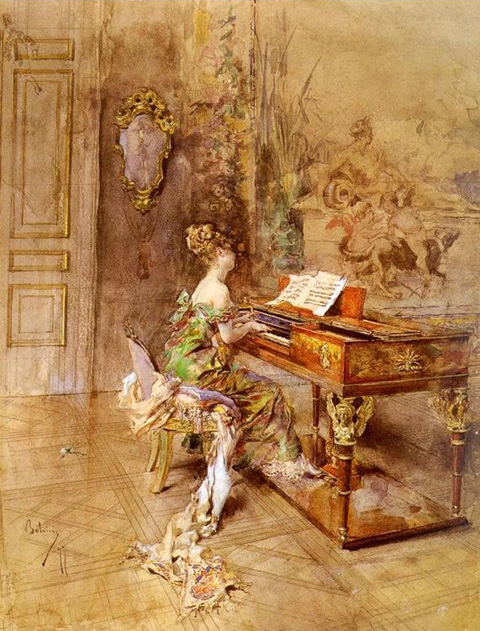

What is initially arresting about these works by Giovanni Boldini is their rococo opulence. It’s as your eye lingers, however, that they become truly riveting. Roiling between specificity and gesture, they seem to be continually resolving themselves. Details emerge, register, then dissolve – each drawing seems to come into focus as your eye roves over it, never quite developing the same way twice. Interesting cat, Boldini – friend of Sargent and Degas, he painted dazzling society portraits, fetching nudes, courtly vignettes, all rendered in a expressive, bold style. Despite some ridiculous confections, most of his work is a pleasure, decadent and masterful.

It casts a spell…. It is a cliche to claim to be held in thrall by powerful work. I don’t know though… I should really not groove on these paintings by Kristine Moran … they are messy, lurid, and emit a spoiled oily decadence. But yet they mesmerize. Utterly arresting, they are caught in a torrid balance between conjuring a real space and depicting a dervish of psychological http://www.mindanews.com/buy-inderal/ spatter. The thick palpable smear of the brush strokes, the extreme saturation of the colors, the Technocolor palettes… it’s like Douglas Sirk’s head exploded… Research on her older work (which takes a bit of googling) yields paintings and drawings rooted in conceptual architecture and the surreal covers of old sci-fi paperbacks. More of her work here and after the jump.

Holy cow… these landscape photographs by Kim Keever seem to indicate she is in possession of a pen sized version of the Genesis Device, the terraforming rocket fired off in Star Trek II: Wrath of Khan. The best ones evoke the the grandeur of Hudson River School painter Frederic Edwin Church’s work… Actually, these are staged in an aquarium, which for me, as an amateur aquarist, makes them even more impressive. (hat tip andrew sullivan.)

1. Andrew Wyeth and John Updike seemed to have a preternatural communion with the fundamentals of their art. Updike apparently brokered a separate and special understanding with the English language. Wyeth seemingly could will individual bristles to do his bidding in a brutally unforgiving medium awash with chance and accident.

2. Both were, fundamentally, sophisticated traditionalists. Neither flinched from the progressive edge of their art. In fact both, for the sheer love of craft, frequently experimented beyond the comfortable boundaries of their mastered style. As a result they were able to continually infuse their renderings with a freshness and modernity that kept their work free of a willfully grumpy stodginess.

3. Their aesthetic sensibilities were rooted in the landscape of rural Pennsylvania. In my own noggin, there is a direct and immediate shortcut from Updike’s descriptions of the sandstone farmhouse he grew up in Plowville to any number of Wyeth’s paintings.

4. Oddly, Updike initially set out to be an artist and graphic illustrator. He attended The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art in London. It was in there and then that E.B. White offered him a position at The New Yorker, setting him on the path to becoming John Updike.

5. Wyeth, it seems, could easily have been an invention of Updike’s. His frail, sickly boyhood could have been inspired by a mix of Updike’s own rural upbringing and with his youthful artistic aspirations. Wyeth’s father, the legendary and formidable illustrator NC Wyeth, embodied pure and lusty storytelling, as well as the heady days of classic newspaper and magazine illustration that Updike so clearly adores. Wyeth’s long, determined dedication to an unwavering artistic vision as the fads and movements of the art world swirl around him make of him a Rabbit Angstrom like barometer, taking the measure of a changing culture. Even the ill fated Helga escapade feel more palpable as a fictional gambit. As Updike puts it in the beginning of his review of the Helga exhibit, “What do you do with the girl next door?” With that one sentence he hauls the entire affair under the purview of his great obsessions. The secret studio sittings, the bracingly lusty implications of the poses, the vectors of adultery and faithfulness, the complex role of Wyeth’s wife, it all feels of a piece with Updike’s milieu. To think what Updike would havr done with the evocative contradictions and elegiac beauty of the scene depicted in one of Wyeth’s last paintings… The sleek, cream and burgundy wood interior of the artist’s private plane, a woman in a immaculate, white, elegant coat staring through the window down at a gritty farmhouse, a tiny toy miniature of the world that Wyeth spent a lifetime mapping in exquisite and painstaking expressive detail.

6. Both men were targets for a certain smarty pants critical set. In the long view, arguments about the “merit” of representational realist vs. abstract art seems rather, um, “academic” and has everything to do with personal aesthetic and ideological affinities and toss-all to do with any external objective measure. Both had their trouser cuffs perpetually nipped by hipster accusations of a certain snobbishness and squareness. Measured against the accumulated bodies of work, how small and prune-faced the given griefs seem!

7. That said, both reputations accumulated scuffs and dings. Wyeth stumbled badly in the gauche hype he whipped up for the Helga paintings, needlessly overshadowing what was simply a worthy addition to his oeuvre. As for Updike, while his essays and the occasional short stories remained sharp and well turned, in his latter years he slipped from the height of his craft. Reviews settled into a predictable, dispiriting series of polite, genial soufflés that inflated what was in essence a consistent three letter critical verdict: “meh.”

8. Updike was an unaffected and perceptive enthusiast of the visual arts. Unsurprisingly, his writing on art is beautifully descriptive, insightful and free of larded cant. In his review of the Wyeth’s Helga paintings he observes that the roughly painted swathes of hatched backgrounds, while surely evocative of the high art abstractions of Franz Kline, are just as suggestive of the background techniques of the great commercial magazine illustrators like Al Parker and Jon Whitcomb. He goes on to suggests that Wyeth’s close comfort with the illustrative tradition helps account for his critical ostracism. Updike, an enthusiast of the American vernacular, is rightly untroubled by the inevitable promiscuous interplay between commercial and fine art.

9. Last year the National Endowment for the Humanities invited Updike to present the Jefferson Lecture, the government’s highest humanities honor. Updike’s lecture was entitled “The Clarity of Things: What Is American about American Art.” It is well, well worth reading. He concludes, fundamentally, that ” The American artist, first born into a continent without museums and art schools, took Nature as his only instructor, and things as his principle study. [He developed] a bias toward the empirical, toward the evidential object in the numinous fullness of its being” Updike builds to that conclusion with a nimble and catholic survey of 200 years of American art, and weaves this common tread to bind together earnest Copley, creamy Sargent and stern Sheeler, arch Warhol and jazzy Pollack. We are all, realists, really.

10. A last convergence. Wyeth often worked in egg tempera, which involves hand-grinding dry powdered pigments into egg yolk. As I was thinking about the exacting preparation and application, it struck me that it served as an unusually apt metaphor for Updike’s prose – Sharp, rich specific details suspended in a flowing medium which quickly hardens, fixing the scene in enameled perpetuity.

(a note: These ruminations are heavily indebted to Lawrence Weschler’s convergences – essays that explore connections and resonances between disparate images or ideas. His amazing and beautifully designed collection, Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences, can be bought here.)

Matt Bednarik, photographer and erstwhile agency associate, has a new show up focusing on his recent trip to Japan. Matt’s work is, as I’ve mentioned before, cerebral and rigorous with a wonderful warm undertow… and it’s at Bus Stop boutique, so art can be happily enjoyed in the context of stylish women’s shoes. Huzzah!

UPDATE: Due to heavy advertising, I regrettably missed the opening. Word is awesome on all fronts. Can’t wait.