Labor Day 2018, Madison, CT

Table of Contents: Culture

The pulpit beneath a carved depiction of the daily ecstasy and rapture of Mary Magdalene, The Basilica of St Maximin, Aix-en-Provence • the pulls of a small organ in the same Basilica • a standard roadside boulangerie, the A52 at Roquevaire, Aix-en-Provence • Some opulence in the Palace of Versailles • some unruly triffids spilling out in the 7th arrondissement • a mannequin on the Rue de la Fontaine au Roi • I spy you up there, above the frieze, amidst yet more opulence in the Palace of Versailles • Welcome to the opulence of the Palace of Versailles! • a folio at Les Puces • Dior Barbie • A horn of plenty amidst the opulence of the Palace of Versailles • An antique pair amongst antiques, St Maximin, Aix-en-Provence • Caryatids by Pierre Lescot in the Louvre • Marianne above the Place de la République

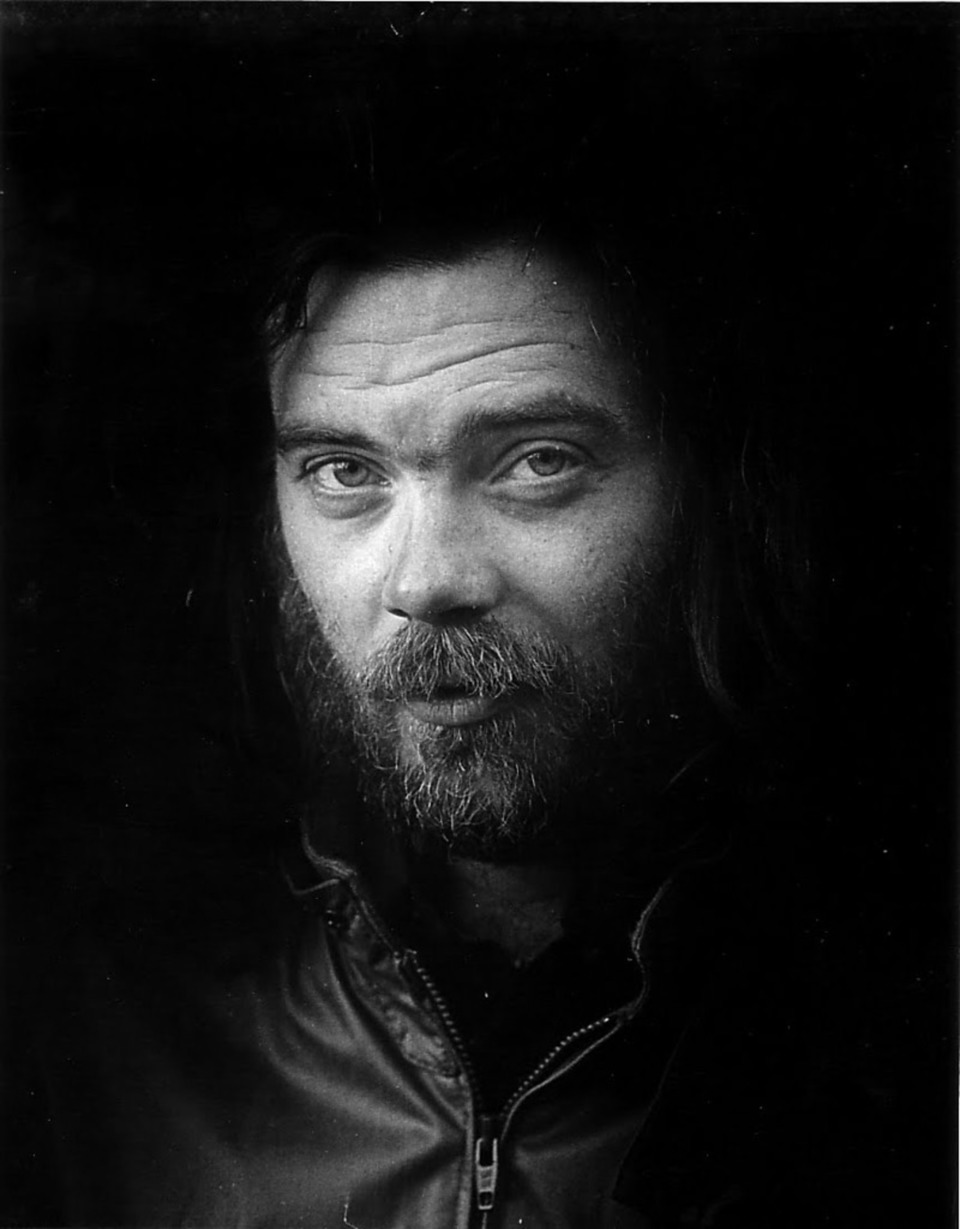

Towards the end Roky told us what it was all about — True love cast out all evil. That was, always, all along, the spell Roky was fervently and desperately casting — True love cast out all evil.

Towards the end Roky told us what it was all about — True love cast out all evil. That was, always, all along, the spell Roky was fervently and desperately casting — True love cast out all evil.

All the two headed dogs, bloody hammers, blieb alien uncreators, the wind and more were lurid carousels for our delight; they also drew off the heat and fevers from his sazzled soul. And his exquisite love songs are the tributes he paid to rock & roll for making his demons dance.

I think thinking about the physics of sadness can tell us something about the person we’re sad about, especially when we don’t know them personally. Like when Bowie died it felt like a celestial object had imploded and vanished. That feels about right. I was in the record store earlier this evening when I found out Roky died. As I took it in, I swear it felt for all the world like he physically left my body. For me Roky lived inside, wound deep and flowering in and around the bright, hot-house things and love, utter, primal, starry eyed love, the kind of love that when you see it, it’ll free you, like magic.

(bottom photo: Roky @ Underground Arts, Philadelphia on September 12th, 2017 / sitting in utter serenity like a psychedelic Totoro amidst a cyclone of sizzlin’ fuzz)

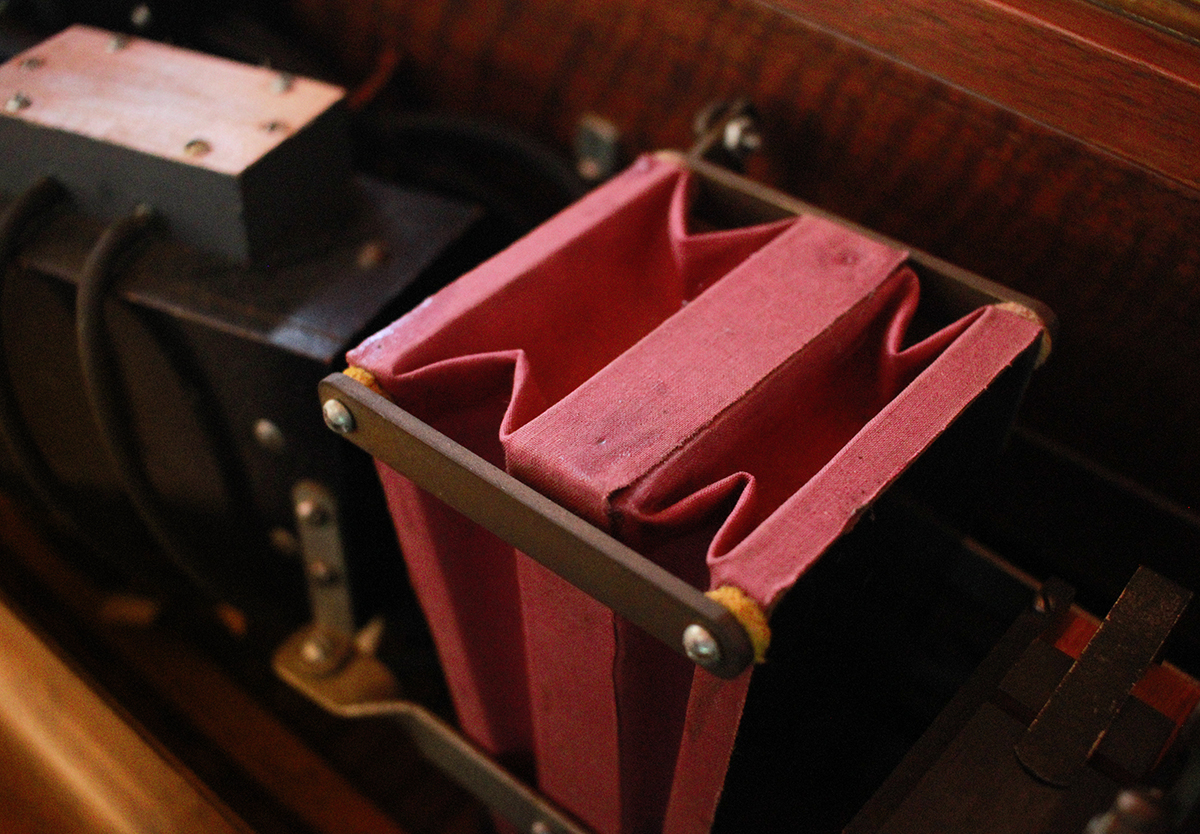

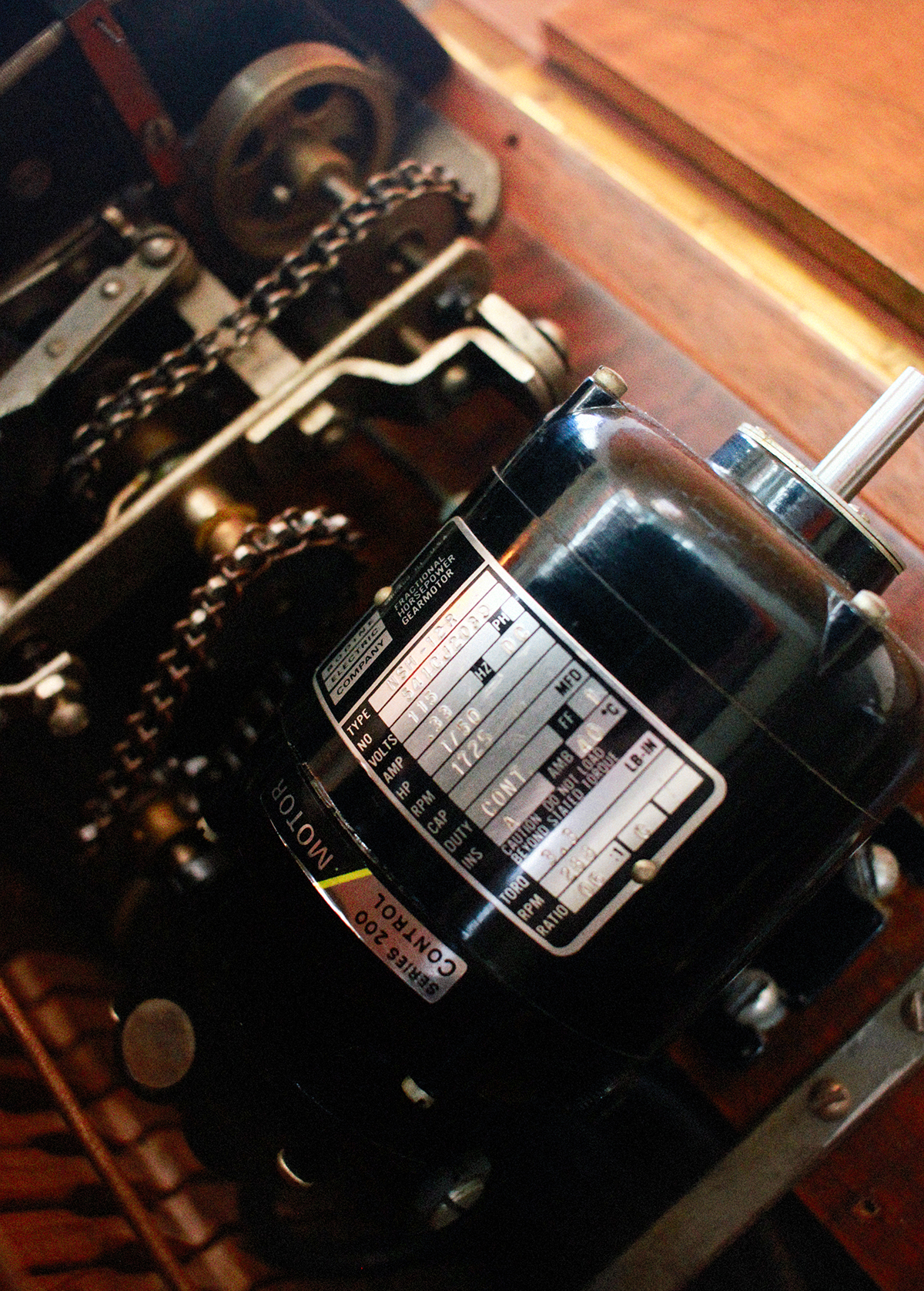

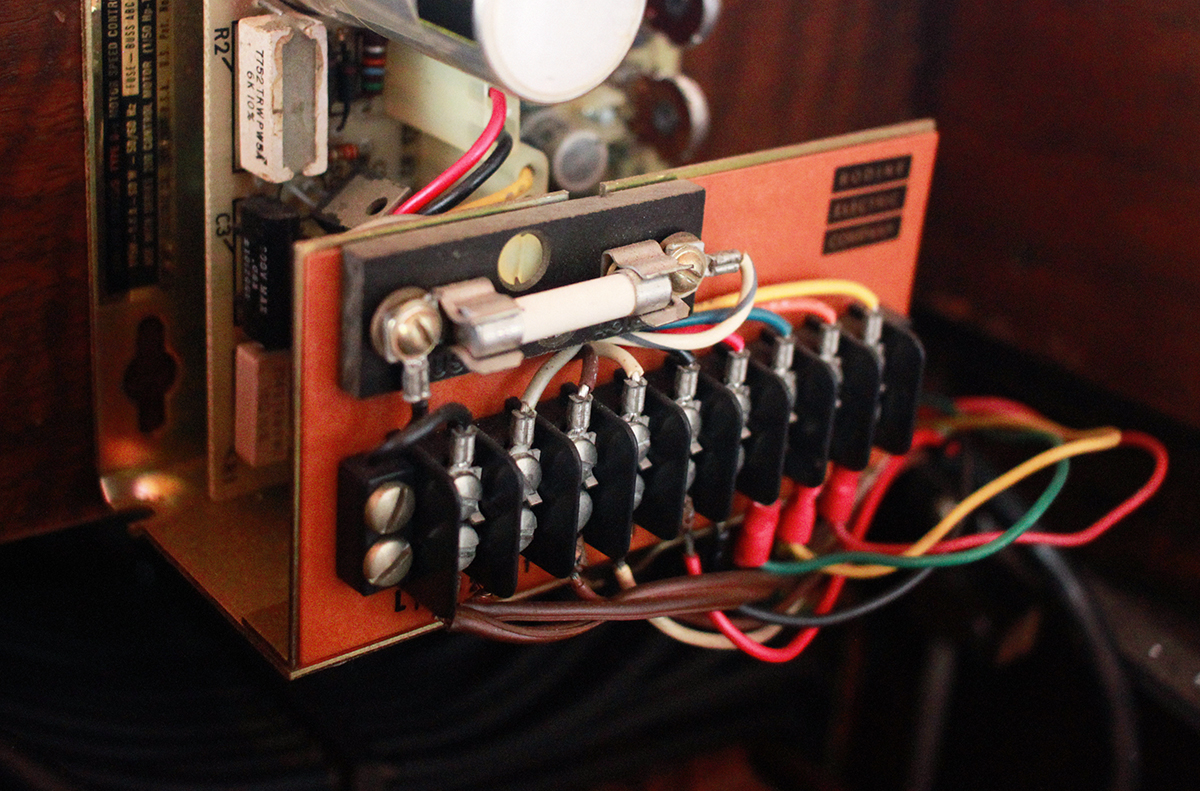

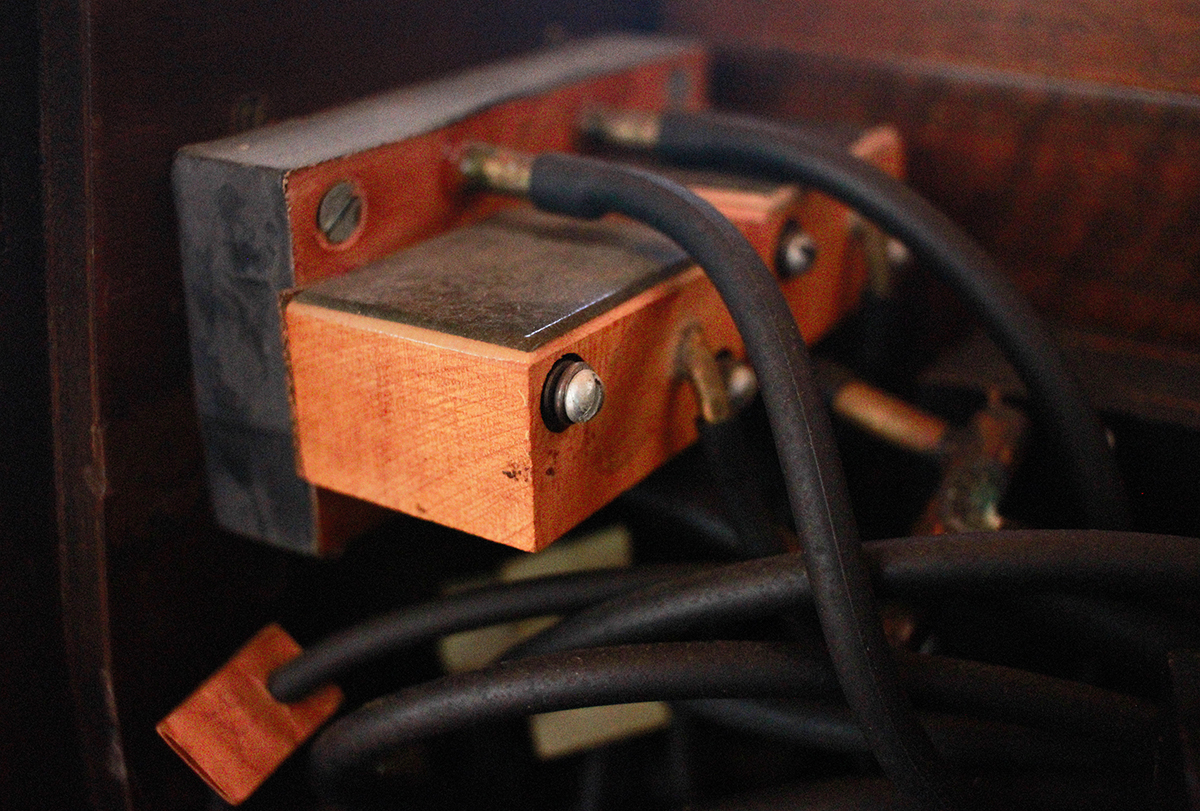

Recently I was staying in a country house in Arkville, New York, nestled in the western Catskill mountains. The house was furnished in fine, spare retail-modernist Design-Within-Reach style and, as a seemingly grand accent, featured a stately grand piano. Lovely. Easy enough to take for granted. However, my brother-in-law, a gifted musician and programmer, sensitive to things like instruments, systems and the built environment, was naturally drawn to inspect this rather grand grand piano a bit more closely. What he discovered was nothing less than an astonishment – grafted throughout the body of this Steinway piano was a massive electrical, analog, mechanical self-playing (or “reproducing”) mechanism. Just exploring the machine, with no understanding or appreciation for its functions, was incredible in itself. Exquisite construction, the combination of engineering, instrumentation and carpentry. It was also profoundly otherworldly, like actually discovering some marooned technology from an alternate steampunk version of our reality. For real.

Recently I was staying in a country house in Arkville, New York, nestled in the western Catskill mountains. The house was furnished in fine, spare retail-modernist Design-Within-Reach style and, as a seemingly grand accent, featured a stately grand piano. Lovely. Easy enough to take for granted. However, my brother-in-law, a gifted musician and programmer, sensitive to things like instruments, systems and the built environment, was naturally drawn to inspect this rather grand grand piano a bit more closely. What he discovered was nothing less than an astonishment – grafted throughout the body of this Steinway piano was a massive electrical, analog, mechanical self-playing (or “reproducing”) mechanism. Just exploring the machine, with no understanding or appreciation for its functions, was incredible in itself. Exquisite construction, the combination of engineering, instrumentation and carpentry. It was also profoundly otherworldly, like actually discovering some marooned technology from an alternate steampunk version of our reality. For real.

Reading about it later only deepened my fascination. The excerpts below, taken from two restoration companies, give a sense of the breathtaking ingenuity of these devices. Consider they debuted in 1914, only a few years after commercial electricity itself…

For anyone with even a glimmer of interest I highly recommend fully going down the rabbit hole on this technology – following the technological details of how these functioned, and how the rolls were recorded – all of it. Gobsmacking.

A full history of the system can be found here. Full restoration notes can be found here and here.

The Reproducing Player Grand Piano was the most technologically advanced form of home entertainment during the early 20th Century. Designed to reproduce a live performance, these instruments could mimic every nuance of a real pianist, giving the illusion of a true live performance in real time. These instruments would have cost as much as $3,500+ new in the 1920s, the cost of a small house. The ultimate home entertainment system of the Gatsby age, these rare pianos were built in small numbers and are quite rare today.

The Steinway & Sons Duo-Art player consists of over 8,200 moving parts… as in all standard reproducing pianos, an electric suction pump powers the playing mechanism and supplies a sufficient level of suction for the maximum loudness needed by the piano. Proprietary dynamic control devices reduce this suction level in various sophisticated ways so that a wide variety of dynamic effects is possible.

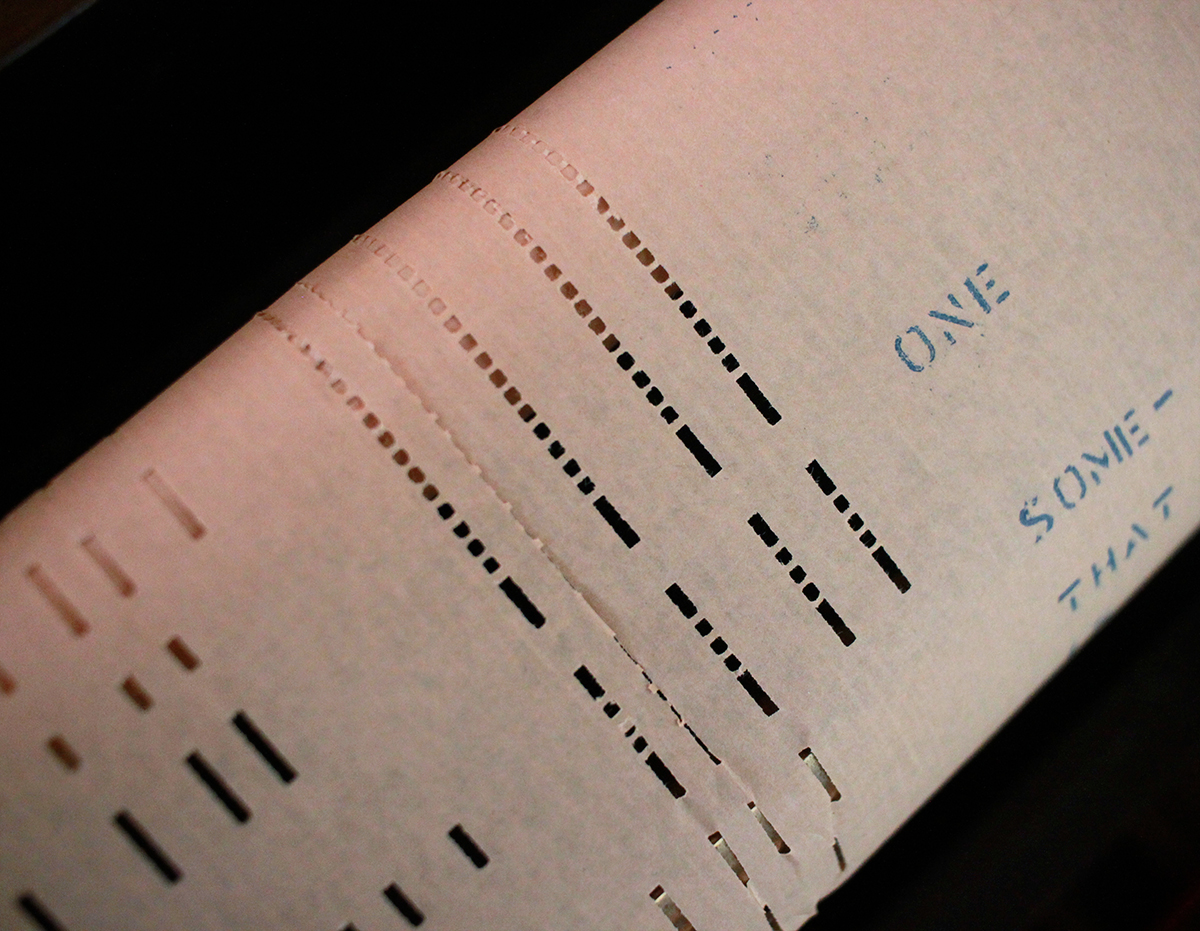

A perforated music roll passes over a tracker bar, which has holes in it connected via many small tubes to the individual note mechanisms of the instrument. At the left-hand edge of the music roll (and also at the right-hand, which is not shown), there are four special perforation positions which do not operate notes…the four dynamic coding perforations on the roll can be combined, allowing for sixteen degrees of dynamic control.

Duo-Art used a real-time perforator to produce an original roll as the artist played. Dynamics were not recorded automatically but were created on the roll as the artist played, by two dials and their associated mechanisms, controlled by the recording producer, who sat to the left and slightly behind the pianist.

Under the keys of the recording piano was a series of electrical contacts which ran through a cable to a separate room, where the rather noisy perforating machine was housed.

Once an Aeolian Duo-Art information original roll had been perforated, the roll was then copied to a much longer stencil roll, on thicker paper, which was then used to produce several copies for editing purposes, known as trials… Lastly, the final trial was approved and signed by the pianist, and became a pattern, to be used as a proofing copy in the manufacture of the roll for commercial sale.

To be great, to be a man of genius, to be famous, to be much loved and much hated; to be much praised and much dispraised; to have a passion for creation and passion for women; to be descended from one of the oldest French families; to be abnormal and inhuman; to have sardonic humor and intense presence of mind; to adore nights more than days—to adore and to detest immensely; to squander much of one’s substance in riotous living, to have a terribly direct eye and as direct a force of hand; to be capable of painting certain things which have never yet existed for us on the canvas; to be angry with his material, as his brutal instincts seize hold on him; these, chosen at random, are certain of the distinguishing qualities of Lautrec.

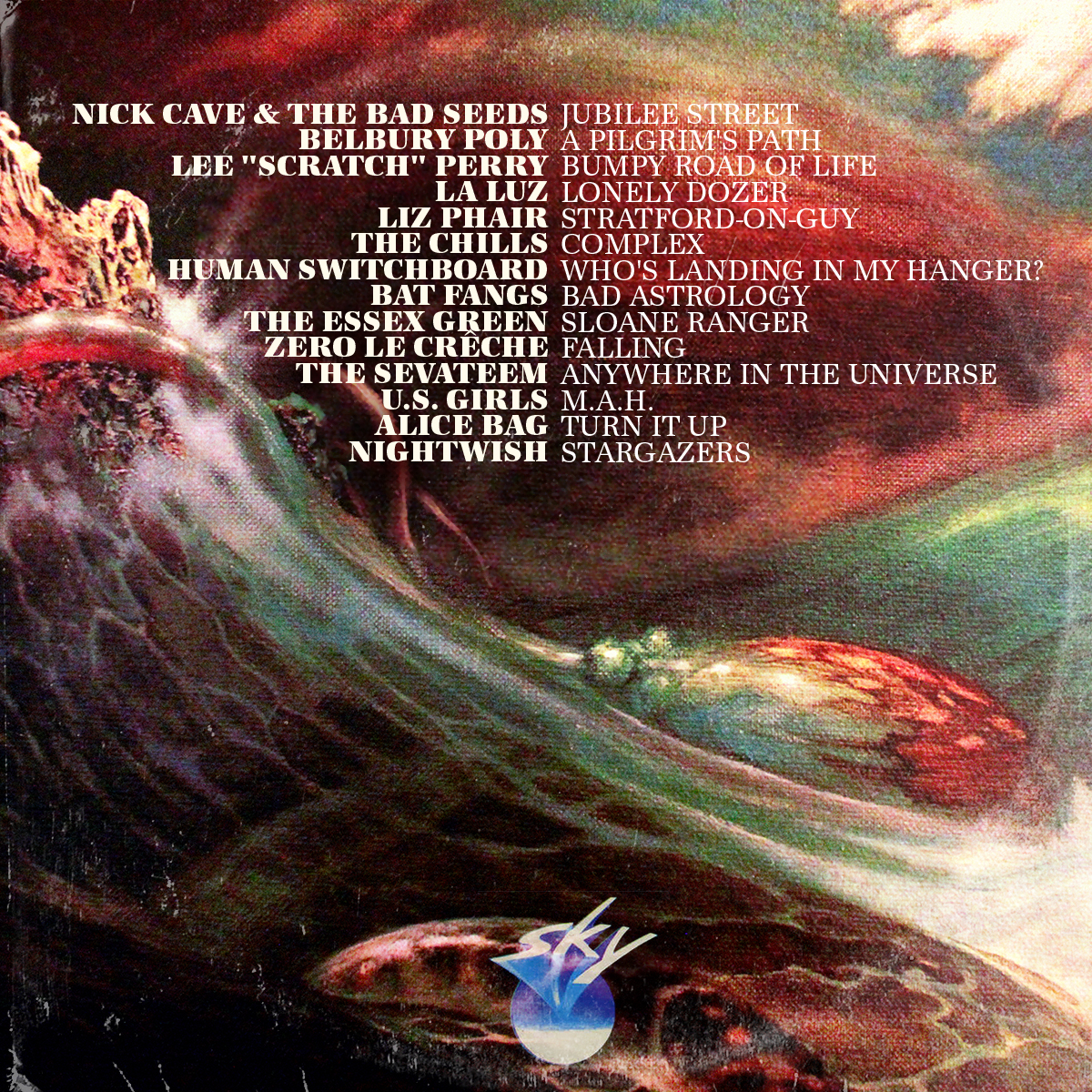

There was a moment, live, as the first half of “Jubilee Street” was rounding the bend that the music suddenly lurched, as if unexpectedly struck with a great force. The band rumbled, then just — detonated; Nick Cave stood, stock still, seemingly absorbing the full force of the blast behind him. Then — he cracked, lengthwise, like a thunderclap. “LOOK AT ME NOW / I’M TRANSFORMING, I’M VIBRATING, I’M GLOWING / LOOK AT ME NOW.” For the rest of the night Nick Cave kept scraping the clouds.

There was a moment, live, as the first half of “Jubilee Street” was rounding the bend that the music suddenly lurched, as if unexpectedly struck with a great force. The band rumbled, then just — detonated; Nick Cave stood, stock still, seemingly absorbing the full force of the blast behind him. Then — he cracked, lengthwise, like a thunderclap. “LOOK AT ME NOW / I’M TRANSFORMING, I’M VIBRATING, I’M GLOWING / LOOK AT ME NOW.” For the rest of the night Nick Cave kept scraping the clouds.

Remember the way the locks, switches and gizmos worked in Aeon Flux? Inscrutable components, switches, and dials would click, whirr, latch, and trip in improbable combinations until the lock gave way, blossoming open like a mechanical flower. Belbury Poly’s groovy puzzle-box collage instrumentals worked on me the same way – BBC library grooves, spooky Hammer film soundtrack flourishes, tinkling harpsichord, hazy bits of stoned dialog, click, whirr, clank, trip, click, release, besotted. High Church of Geek ambient.

Dunno ’bout you but my theory is that Lee Scratch Perry’s Black Album is, in fact, the latest in the series of mysterious dark Monoliths left scattered across the universe by forgotten extraterrestrials lost forever to the hazy mists of galactic time.

Musically, Philadelphia is generally pretty lush, but surf-wise it’s a parched, horizon blurring desert. It was fortuitous then, that live, California’s La Luz were short a keyboardist, because guitarist Shana Cleveland just flat tore up — shredding, barreling, spraying gnarly surf leads all over every tune. A mirage on fire, a mirage dressed in fetching matching sailor suits, on fire, to be precise. It was awesome. On the Bandcamp page for this year’s Floating Features, one “Ingwit” sought to congratulate La Luz “for somehow managing to take the heat shimmer on a long stretch of summer blacktop and press it onto vinyl.” I’m with Ingwit – well put, and well done ladies. \shaka/

My enthusiasm for Liz Phair used to run from the beginning of the song “Supernova” to the end, peaking with “Your kisses are as wicked as an F-16. And you fuck like a volcano, and you’re everything to me.” Maximum hella romantic! “Stratford-on-guy” randomly unspooled one afternoon from the depths of my electric phone and I was totally mesmerized. What a weird, gorgeous fever dream. I immediately played it a few more times in a row, hungry for its hypnotic incantations. “It took an hour, maybe a day. But once I really listened the noise just fell away.” Nice then, that this little epiphany coincided with this years’ 30th anniversary of Exile in Guyville releases. I guess I’m finally far enough from Guyville to dig the exile.

The recently revivified Chills have been a deeply welcome gift these past few years. On his new record Snowbound, Martin Phillips finally leaves behind his legendary cache of demos and sketches he’s mined for nearly four decades. The new, freshly written songs are largely a collective atonement – grappling and reconciling with years of travails, addiction, sundered relationships and shredded dreams. “Complex,” while rooted in those themes, utterly transcends them, emerging as one of best songs in an already storied songbook. A giant tune, a world in miniature, a new wave roller-coster inside a snow globe. Literally literally.

It took a while, but I finally fully grok and groove the jittery, grimy white heat rhythms of mid 70s New York City punk and their sonic cousins in likeminded boroughs. Human Switchboard’s Who’s Landing In My Hanger LP was a crate-digging score based on a recollected shard of a positive review from an old Trouser Press record guide. What a blast! NYC by way of Cleveland like the Dead Boys, it’s all glorious fan-fic takes on Deborah Harry and Lou Reed stylings, Modern Lovers primitivism and Television’s ramshackle ambition.

The first fang is is for all the rad bell-bottomed boogie bands led by badass lasses this year: Lucifer, Death Valley Girls, Ruby the Hatchet – non of whom, however, could match the bite of fang two – Betsy Wright. Wright took a break from being Mary Timony’s swashbuckling wing-woman in Ex Hex to grand marshal the 28 minute hesher parade that is the Bat Fangs LP. One of their t-shirts depicts a screaming bat with three yellow eyes, ears pointed like spikes, surrounded by concentric bands of melting neon. Every song on this record sounds just like that bat looks. Live — goodness gracious — Wright is a sneering, kicking, grinning, soloing, guitar-pointing total fucking rock monster. She also has a supremely boss collection of catsuits, boy’s small-town athletic shirts, and vintage metal T’s. Between the chops and the flair Wright might be the foxiest performer I have ever seen on stage, ever. When we need someone to represent *rock-n-roll* to aliens, send Betsy Wright.

In 2002, on Halloween, the Essex Green played a CMJ Music Marathon showcase at CBGBs dressed as the Royal Tenenbaums. Their autumnal reunion this year was a welcome occasion for this aging hipster to revisit a time when everything about that sentence was still fresh (or simply existed.) And I never tire of their erudite preppy boho fixations (“Slone Ranger” indeed) nor the burr in Sasha Bell’s voice.

With the release of Silhouettes and Statues Goth rock finally has gotten its archeological exhumation — the results of which are as dense and indispensable as the full Nuggets box set was for garage rock. Released in mid-2017, it’s taken me the better part of a year to explore its murky depths. Treasures and pick-ups abound, (amid swaths of utter muck – nothing rots like bad Goth) Zero Le Creche’s glammy-boomy obscurity “Last Year’s Wife” led down a hidey hole to the wonderful Psychedelic Furs/Bauhaus (right? right.) mashup of “Falling” which dominated the front half of this year’s groovin’.

This year the Sevateem self released Caves, a 16-track indie-electronic pop album inspired by an iconic classic Doctor Who episode from the early 80s. In “Anywhere In The Universe” the Doctor’s companion wonders why he never takes her anywhere nice. (The rationale for the spareness of description, of course, is that even plainspoken it will either engender waves of high geek appreciation, or remain as profoundly un-compelling as the manner in which its been described. Care for a Jelly baby? )

When I first tuned in Meg Remy’s US Girls were a profoundly insular affair, jerry-rigged transistor-kit transmissions of girl-group glitch outs. But recently she’s pointed her antenna towards the outside world, moving from secret wavelengths to broadcast frequencies. Her sound has filled out, shaped by wily and pop savvy comrades with some seriously deep chops. Live, touring behind her astonishing In a Poem Unlimited, I kept thinking of, honestly, Bowie. Bowie the avant grade pied piper, moving from station to station, seducing listeners into his jangled, cut up art along danceable grooves and modern love. Remy’s weird is going pro.

Alice Bag’s reemergence has been absolutely exhilarating. Bag was a major dynamo in the early LA punk rock scene, fronting the band the Bags, appearing as the Alice Bag Band in the seminal Decline of Western Civilization documentary, running wild in the streets with accomplices like Belinda Go-Go, Patricia Morrison and Pleasant Gehman (go google ’em all). She later worked for many years as a teacher, while remaining politically engaged as a Chicana and feminist activist. In 2016 she released her first solo record (and first LP ever, considering the Bags never released more than a few singles) and it was a total knockout — a swaggering blend of snarling punk, brassy girl group and Mexican folk. The record was personally and socially political – a bracing reminder how essential and genuinely inspirational punk could and can be. This year she released Blueprint, a another equally urgent and beautifully arranged salvo. Live, the double barreled opening of Bag’s classic “Babylonian Gorgon” into the new “Turn it Up” was seismic — raw, snarling righteous punk bliss as urgent, and more necessary, than ever.

Ok – straight up – The last track will be of limited or little interest to some, perhaps many. I thought it would be of limited interest to me, to wit — Finnish, operatic, power metal. Again — Finnish, operatic, power metal. Perhaps the phrase repels? For me it beckoned – strictly at first, as a curiosity. Encountering a passing reference to this curious amalgam I was led, as all quests for the essence of Finnish, operatic, power metal do, into the realm of Nightwish. First I read, amused; then I listened and was — utterly delighted (that is, while listening I experienced a high degree of gratification and pleasure.) It was gloriously absurd, but breathtaking in the scope of its foolhardy earnest bat-shit-ness. I immediately ordered their 1998 album Oceanborn, roundly considered definitive. While I waited for it to arrive I did experience a spasm of second guessing, a shuddering sense of “Surely not seriously.” One spin through Oceanborn’s rainbow laser glitter symphonies and I was even more delighted – that is, experiencing even higher degrees of gratification and pleasure. I could go on, and on, and many do, the earth over (Vice Magazine even prepared a thorough guide to the world of Nightwish, should you, um, wish.) Then I saw them live. Fucking lords of Asgard they were astonishing!! 6 magnificent Vikings by way of Marvel ‘s Jack Kirby or Branagh’s Thor — a chimera of Iron Maiden, Meatloaf and Brünnhilde fronted by a legit Valkyrie named Floor Jansen! Every song sounded like 20 technicolor rockets red-glare, even before they actually fired 20 technicolor rockets from the stage. Again. And again. A Ragnarock of delight, gratification and pleasure.

DOWNLOAD THE COMP HERE.

BONUS COMPILATION: This year also marks the 10th year of consecutive yearly mixes. As such, I’m commemorating this anniversary with a special compilation featuring a track from each year. Unlike the main mixes, which mix new, live and discovered music of the past year, each track here was released in the year it represents. Enjoy, cheers, etc.

DOWNLOAD HERE.

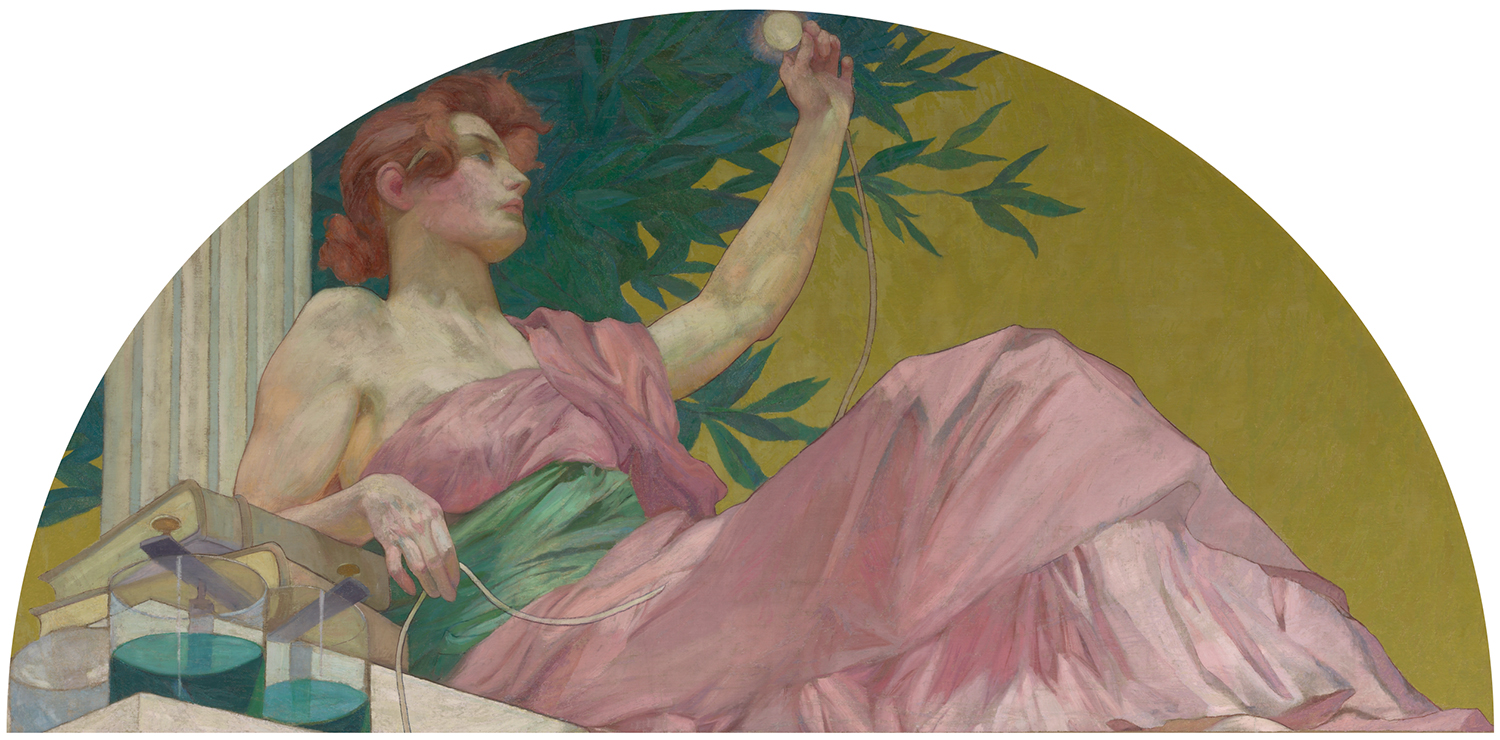

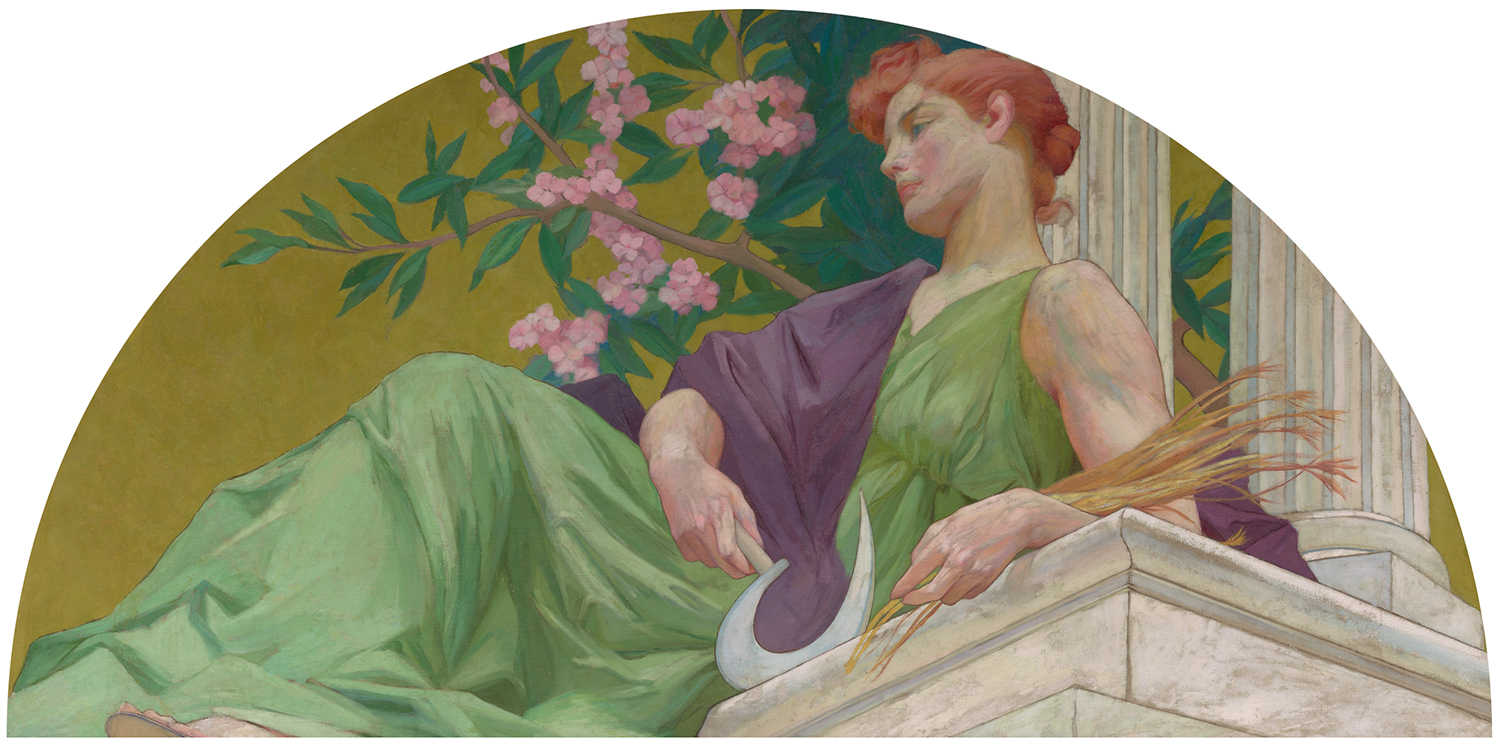

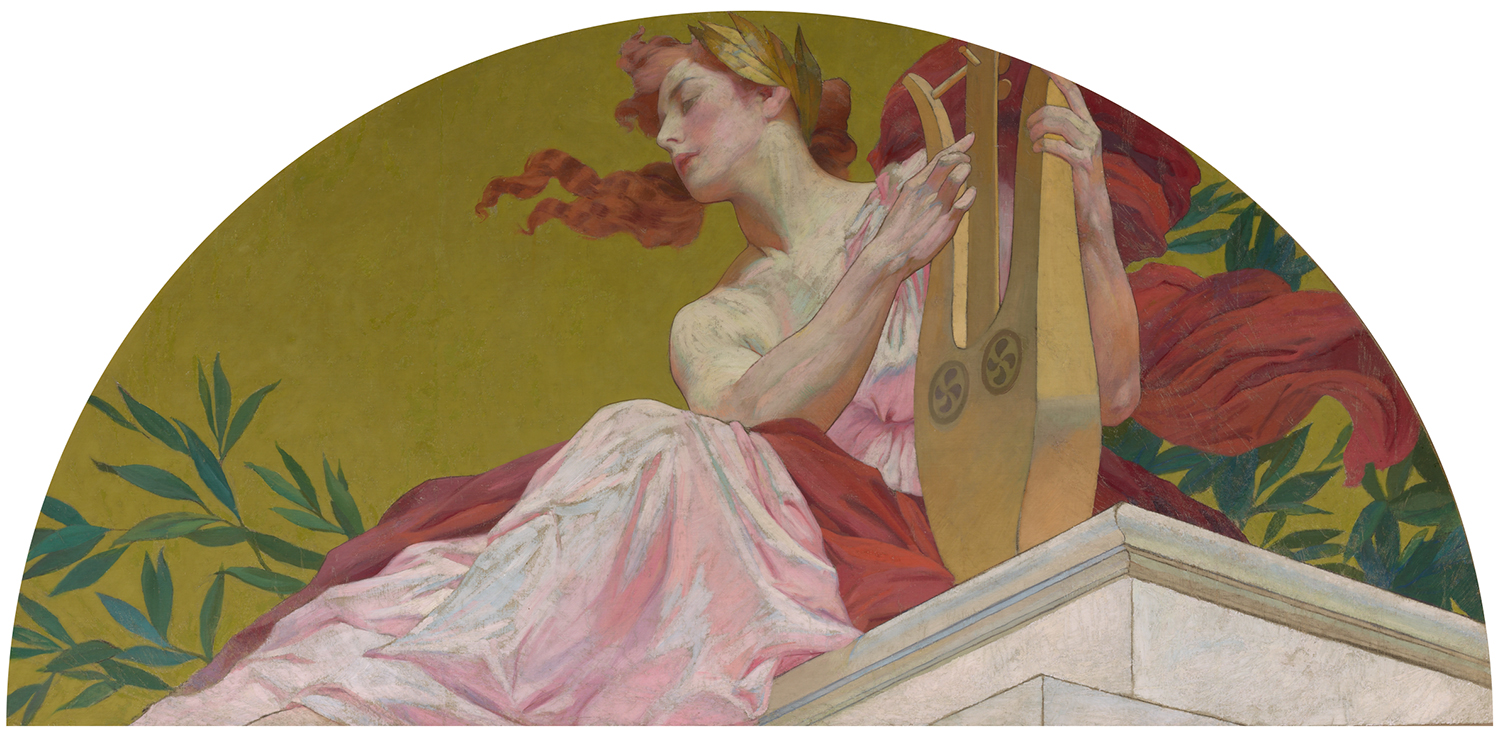

On a recent trip to the Yale University Art Gallery I was struck by these lunettes installed in a series high above the moulding of a gallery of 19th century American paintings.

On a recent trip to the Yale University Art Gallery I was struck by these lunettes installed in a series high above the moulding of a gallery of 19th century American paintings.

Painted by by Harry Siddons Mowbray they were commissioned as part of a large decorative scheme for the New York mansion of railroad tycoon Collis Potter Huntington. Six of the muses are traditional, while Mowbray invented three new ones — Painting, Agriculture and Science and Electricity.

At first thier cumulative effect was somewhat disorienting – they’re mounted so high that they sit nearly past the terminal angle of the neck. I had to bend backwards to take them in fully. Once I could focus though, I was mesmerized. What a presence each possessed, enhanced by their slightly exaggerated perspectives. And what vivid style — watery and fluid coloring held taught by graphic contours — a gorgeous hybrid evoking academic painting, vintage advertising illustration, social realist propaganda and heroic comics. Make my muses Mowbray’s!

More information here. From the top: Muse of Electricity, Muse of Painting, Muse of Agriculture, Muse of Music, Muse of Lyric Poetry, Muse of Tragedy, Muse of Comedy, Muse of Astronomy.

> DOWNLOAD THE COMP HERE

> DOWNLOAD THE COMP HERE

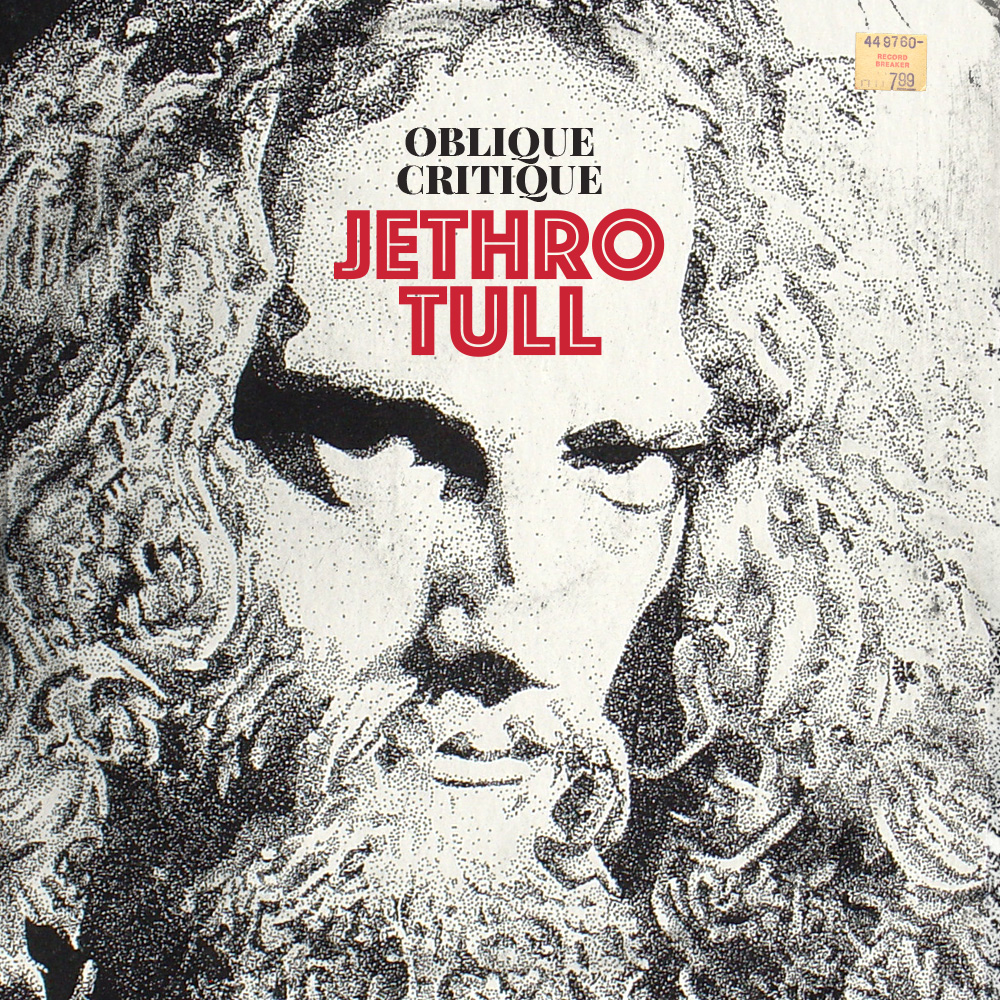

Jethro Tull has been, consistently and ardently, my favorite band for the last 30 years.

Wherever and however far I might drift — across oceans of punk, pop, prog & psychedelia, into sunken caves of dub or swampy lagoons of goth, down pulsing Krautrock channels, upended by typhoons of metal — I always tie back up with Tull.1

My conversion experience occurred in profoundly improbable circumstances. In 1988 I was in high school, peaking with hardcore punk rock fever. Amongst our rag-tag handful of like-minded misfits, Suffer, a new album by Bad Religion (back then a far lesser known band) was gathering some serious killer buzz. Finally, one kid scored it from an older brother and brought it in for me to gym class. I promptly inserted the home recorded tape into my AIWA walkman.

Now, if you recall, the key feature of mid-period Walkmen was “auto reverse” functionality allowing you to play either side of the tape without physically reversing the cassette. Pressing play, then, I entered a singular, un-repeatable fantasia where basically, for about maybe 15 seconds, I thought some random snippet of what turned out to be Jethro Tull was the new Bad Religion. And fucking loving it. A little perplexing, surely, but yea, fucking loving it. Soon enough I regained my bearings and flipped over to the other side, promptly losing myself in the masterwork that was Suffer.2

But in those disorienting seconds the sonic allure of Jethro Tull took hold. Then and there, I managed to grok a concentrated dose of their jam — those sizzling, off-kilter riffs, improbable melodies, all cinched up tight by the singular rough velvet timbre of Ian Anderson’s voice. And the whole flute thing. So, even as I remained the doctrinaire punk, the spell and the die were cast.3

My enthusiasm for Tull has often struck others as a bit incongruous, given my other musical pleasures and predilections. Over the years, one cat or another has asked me to put together a representative mix of their tunes. While these requests are rooted, I’m sure, in genuine open curiosity, I always detect a flash of a skeptical edge, a pointed demand to justify Tull’s place in my celestial hierarchy. So, in recognition of their 50th year, and my three decades of devoted fan-hood, it feels like high time I take my own measure of their radness.

On Jethro Tull’s “greatest hits” there is a mighty and widely shared consensus. The songs collected on the 1976 best-of LP’s M.U. The Best of Jethro Tull, with the exception of one fan-rewarding rarity, are canonical, enduring FM rock radio staples. However Tull’s stature as classic rock powerhouse draws selectively from a deeply weird, idiosyncratic body of work.4

This particular selection of tunes, first and foremost, is my own rendering of Jethro Tull’s singular sensibility — drawing at times on key rarities, alternate recordings, live performances, and deep album cuts. This is not showboating fan service or willful obscurantism. Rather, it is an effort to make a a broader case for Tull as an absolutely killer psychedelic rock band of particular interest to those inclined (like the reputation enjoyed, let’s say, by Van Der Graf Generator). All the songs are in some way fundamental to the band’s identity, while also being top-grade left-of-the-dial rock and roll.

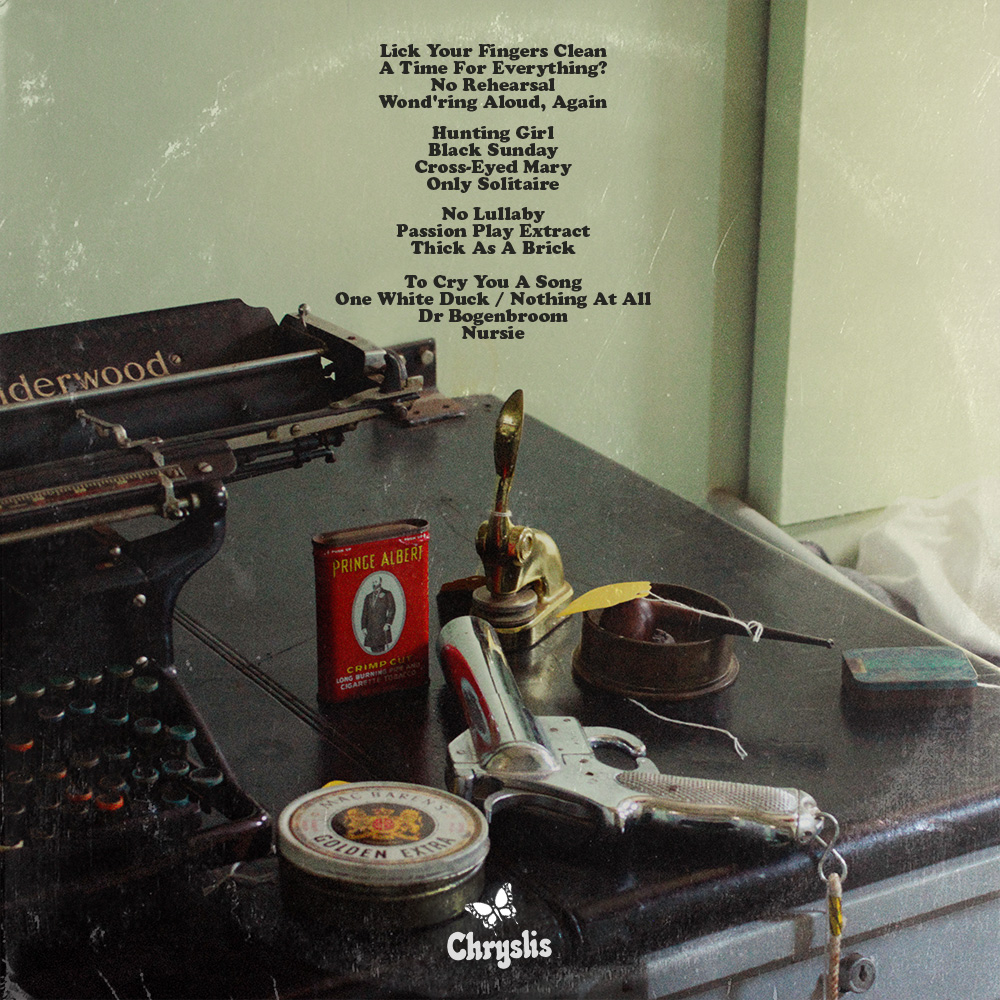

For me Jethro Tull’s classic period is comprised of four rather distinct phases which flow and feather into one other at the edges.5 By around 1969 Anderson had established nearly complete aesthetic control of the band. He was still working within and inside recognized rock forms, but songs were beginning to be yanked into distinctive shapes (A Time For Everything?, To Cry You A Song, Dr Bogenbroom) or stretched out into ambitious suites (Wondering Aloud, Again). All the while, though, riffs remained the anchor and engine of the songs.6

With 1971’s Aqualung, Anderson’s titanic talent, personal passions and quirks (and, frankly, ego) had utterly subsumed the band. Here begin his alchemical experiments with various ratios of rock, English folk, classical, and Elizabethan music. Lyrically he also sets off alone for parts unknown, with his mix of religious allegory, detailed character sketches, verbal dexterity, general inscrutability, and no small dose of Python-esque humor. This era simultaneously produced their biggest popular successes, fiercest critical drubbings, and acres of stunning, exhilarating and challenging music (Cross-Eyed Mary,7 Lick Your Fingers Clean, No Rehearsal)

Around this time Tull had also cemented its reputation as a crushingly stellar live act (No Lullaby, Passion Play Extract, Thick As A Brick). Impeccable, muscular musicianship, rollercoaster set-lists, all wildly energized by Anderson’s legendary showmanship – a galvanizing, whirling, one-footed, flute brandishing, cod-pieced dervish.

Tull’s massive sales and live success had the additional benefit of inoculating the band, and especially Anderson, against any permanent scarring from what was a turbulent and tumultuous period of peak fame, popularity and exposure. By the mid 70’s Anderson was purposely withdrawing from the show-biz hullaballoo, spending more and more time in various countrysides. In 1978 he bought and moved to an estate out by the Outer Hebrides in remote Scotland. A growing interest in folklore, fantasy tales and British rural traditions began to profoundly shape Anderson’s writing (Hunting Girl). This rural sensibility culminated in a trilogy of folk rock records with which Tull closed out the decade.

This period, much beloved by fans, was memorialized by the double LP live album Bursting Out and came to an abrupt and tragic end with the death in 1979 of Tull’s bassist John Glascock. Disbanding the band indefinitely, Anderson began work on a solo record which reflected his bourgeoning interest in synthesizers.

Anderson’s label Chrysalis insisted that the record be credited to the band, thus forcibly inaugurating Jethro Tull’s quirky electronic folk era. Although it yielded some choice sides (Black Sunday) and arguably led to one last classic album, 1982’s Broadsword and the Beast,8 this new tack remained divisive among fans, critically thrashed, and profoundly out of sync with general audiences. Anderson mined this sound for one more record with rapidly diminishing returns.9

Meanwhile, all along, weaving and braiding through these wild knotty morphings was Anderson’s steady, almost devotional, composition of exquisite acoustic guitar songs (Only Solitaire, One White Duck / Nothing At All, Nursie). Regularly deployed on every album, taken together they comprise an alternate songbook of consistently remarkable beauty and craft.

The title Oblique Critique is a reversal of “Critique Oblique,” the title of a segment of 1972’s single song-length record A Passion Play. Besides being an apt title, it’s fitting that it’s taken from a record that is nothing less than Tull apotheosis – Majestic, exhilarating, wildly ambitious, overthought, dead serious, ostentatiously clever, in patches profoundly silly, passionately beloved by fans (except by those that passionately dislike it), reviled by the rock “intelligencia,” and utterly impenetrable to the uninitiated. And of course, stateside, it went to #1 on the charts.

Front cover art by Rebecca Caviness

Back cover photo by Dan Shepelavy

> DOWNLOAD THE COMP HERE

Some notes, for those inclined…

1 An island which I imagine to be very much like the the actual Scottish island of Skye, home to the Strathaird Estate which Tull’s Ian Anderson bought and moved to in 1978. Scottish mountaineer William Hutchison Murray described the island as “sixty miles long, but what might be its breadth is beyond the ingenuity of man to state.” There Anderson began his storied adventures in commercial salmon fishing. I always imaged its verdant rolling lands to be patrolled by colonies of Anderson’s beloved Bengal cats — a totally bad-ass domestic house cat developed to look like leopards or tigers.

2 thereby establishing my second favorite band of all time – Bad Religion. The Jethro Tull/Bad Religion connection gets even more uncanny. Prior to Suffer, Bad Religion had released its infamous sophomore LP, Into the Unknown. In bewildering contrast to their rough hardcore debut the new record was a reverb drenched, organ swirled, heady psych record that had, as some critics pointed out, more in common with Hawkwind than any known punk reference points (If that sounds pretty amazing it’s because it is. Into the Unknown is an ace record.) It caused a mighty kerfuffle, helped precipitate the bands’ breakup, and was largely disowned after it’s release and hostile reception. In an later interview Bad Religion’s singer Greg Graffin explained that while he was still immersed in the hardcore scene he had developed an powerful affection for Tull and felt compelled to write a set of like-minded songs. He felt it was the most punk rock thing he could do.

3 1988 was a pretty exciting time to have been introduced to Tull. The year prior had seen the release of Crest of A Knave, seen as something of a comeback after 1984’s listless Under Wraps. Knave’s lead single, the (honestly) atrocious “Steel Monkey,” famously and improbably won the inaugural Heavy Metal Grammy award that year, beating out the third band in my high school era holy trinity: Metallica)

Crest of A Knave was also the first record made after Anderson’s battle with a significant throat infection that permanently cleaved off the upper registers of his voice. Although he has gamely and often deftly adjusted his new material and live arrangements to compensate, the music has dimmed overall a bit as a result.

What was seismic in 1988 was the release of the massive 5LP box set 20 Years of Jethro Tull. One of the best fan-focused box sets ever released it featured over four hours of largely unreleased material. Fragments of legendarily scrapped albums, enough rare B-sides to turn their parent records into double LP’s, revelatory studio outtakes and alternate versions — with one stroke it presented a massive and fascinating expansion of Tull’s classic oeuvre.

4 A dynamic they share with, for example, Roxy Music, who’s silky hits can be defiantly at odds with their prickly and at times aggressively odd catalog. This is in contrast, I’d argue, with other prog/glam/AOR/stadium superstars like Pink Floyd, the Who, or Yes where the “hits” and the rest of the oeuvre are much more of a piece. Incidentally, Roxy opened for Tull on their 1972 tour – with both bands at the apex of their powers it must have been astonishing.

5 I have a generally strong allergy to the blues, and as a result don’t really much rate or personally enjoy the first two Tull studio LPs. However, for blues-inclined listeners they have much to offer, not the least of which is tracking Anderson’s take on and emergence from the form. And Anderson clearly considers it a legit component of their overall legacy as he has occasionally returned to this period live.

6 In his review of 1970’s Benefit, critic Robert Christgau, by no measure a fan of the band (“I find [their] success very depressing”) allowed that Anderson “does have one undeniable gift, though — he knows how to deploy riffs.”

7 There exists an endearing bonhomie between the classic British metal scene and Tull. In 1968 Sabbath’s Tony Iommi did a split second stint as a Tull member, and remained a pal and supporter ever since. Anderson and Lemmy were longstanding and unlikely chums (Anderson titled a superb recently discovered outtake from Songs From the Wood “Old Aces Die Hard” in tribute to Lemmy.) Iron Maiden, particularity, are massive Tull fans. Their barnstorming cover of “Crosseyed Mary” is a glorious toast and fond tribute — and for me, the singular instance of a Tull cover worth listening to.

8 In putting together this compilation I was surprised that Broadsword and the Beast, an album I adore, stubbornly resisted representation. It is a tremendously entertaining record, especially in its expanded nearly double LP form, with many personal favorites (“The Clasp,” “Pussy Willow,” “Jack Frost and the Hooded Crow,” “Down At the End of Your Road”) But the songs withered and wobbled when taken out of context. Ultimately I think Broadsword is a particularly insular record, and one that makes sense only within the context of deep fandom. It is also a profoundly geeky album, with a heavy D&D vibe that may be for converts only.

9 In retrospect the run of albums 1988’s Crest of a Knave inaugurated are, under even the most charitable lights, a spotty patch. The muse stirred a bit on two largely acoustic solo records in the early ‘aughts. However, the real “comeback” would have to wait until 2012 when Anderson, now operating solo, unexpectedly released a “sequel” to 1972’s Thick as a Brick.

The only thing more absurd than the idea of a sequel to this famously obtuse prog-rock masterpiece is how decent it actually is. Anderson had assembled a virtuoso band that scrupulously recreated the distinctive sonics of 70’s era Tull and he delivered a set of songs to suit. This led in short order to Anderson’s definitive late career triumph Homo Erraticus, another sprawling throwback prog epic, this time wholly original in topics, themes and tunes. Highly recommended.

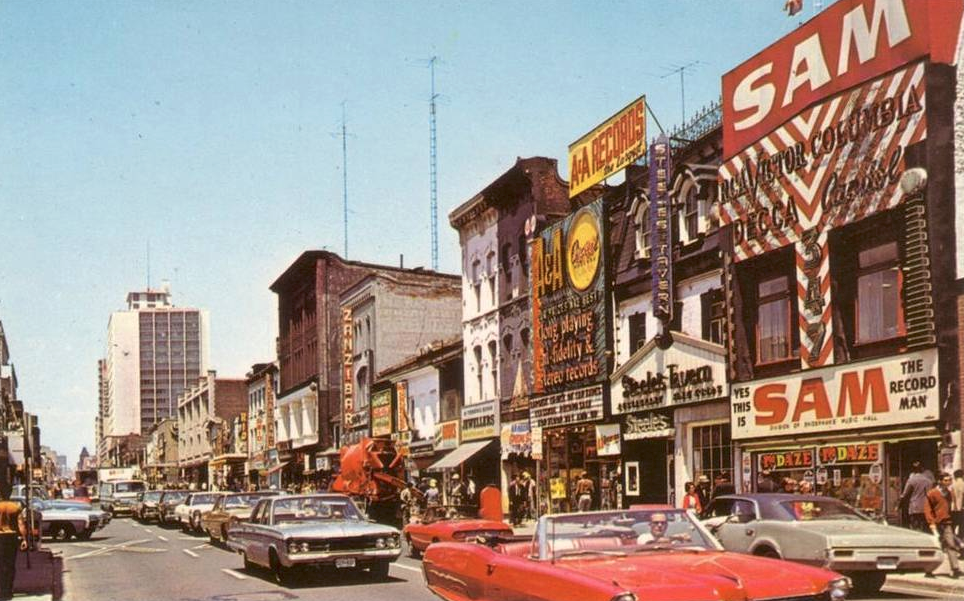

On a recent unexpected layover in Toronto I happened to see, hoisted high, high above a gloomy black glass office building in Dundas Square, this wonderful sign. Double barreled neon flashing records proclaiming, twice, that YES, THIS IS SAM, THE RECORD MAN! YES, THIS IS SAM, THE RECORD MAN! Wonderful! Wonderful! A little research revealed the legacy of a one proud Canadian record store chain – a blaring hybrid of Crazy Eddie and Tower Records. Sigh.

On a recent unexpected layover in Toronto I happened to see, hoisted high, high above a gloomy black glass office building in Dundas Square, this wonderful sign. Double barreled neon flashing records proclaiming, twice, that YES, THIS IS SAM, THE RECORD MAN! YES, THIS IS SAM, THE RECORD MAN! Wonderful! Wonderful! A little research revealed the legacy of a one proud Canadian record store chain – a blaring hybrid of Crazy Eddie and Tower Records. Sigh.

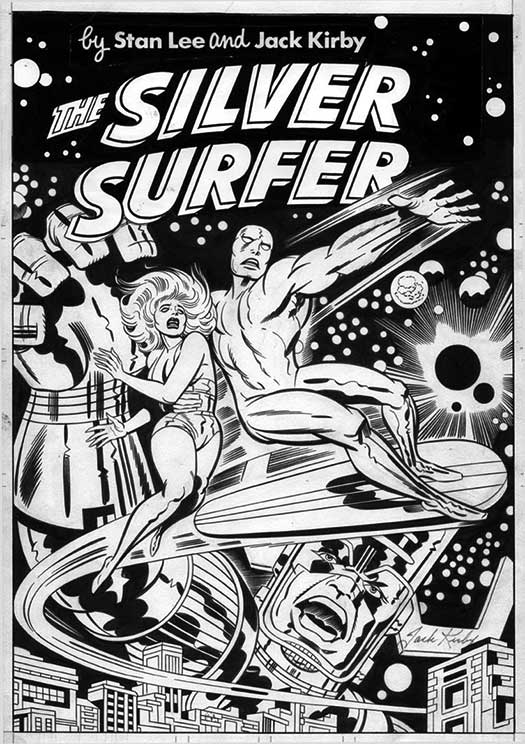

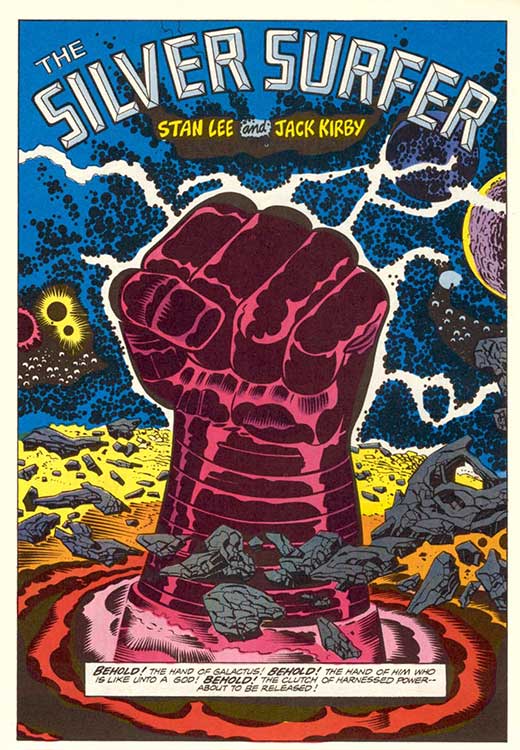

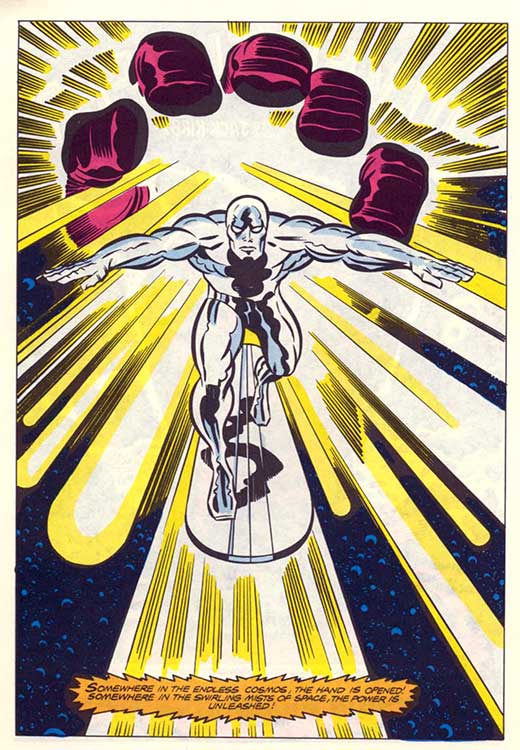

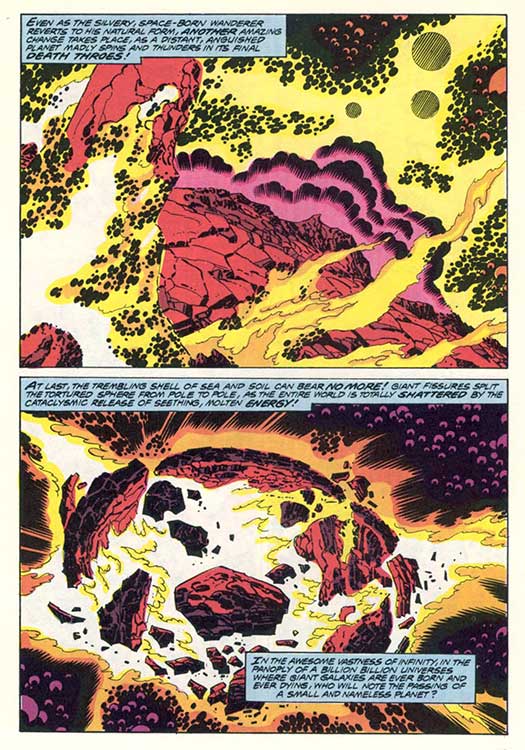

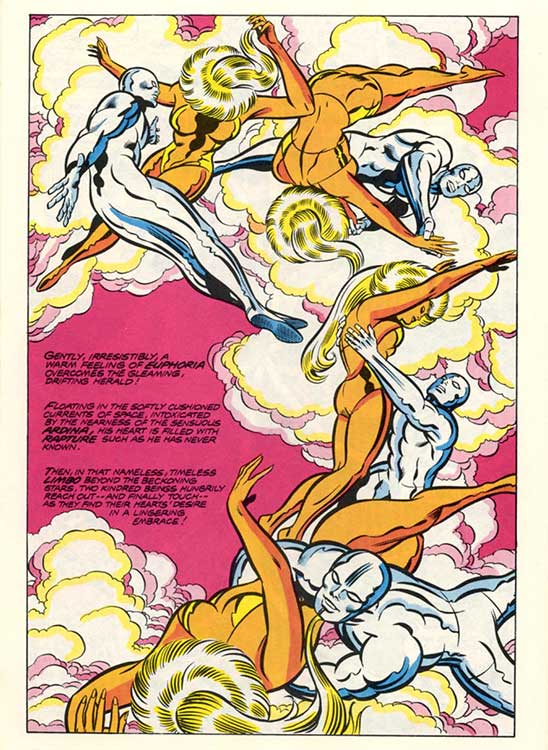

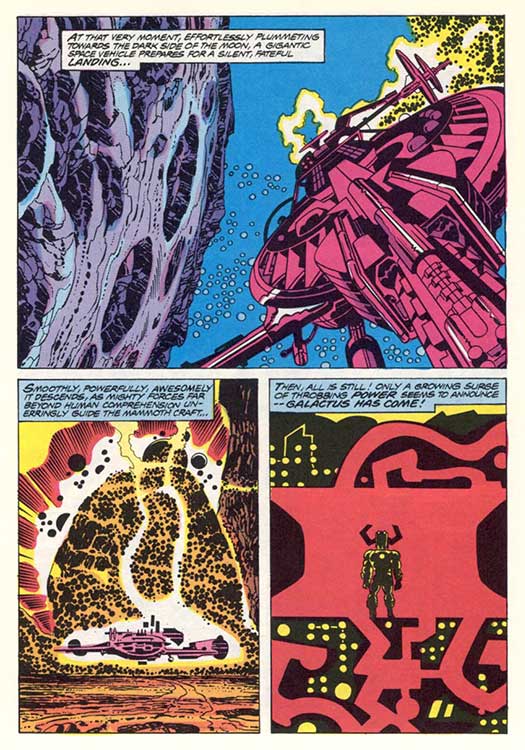

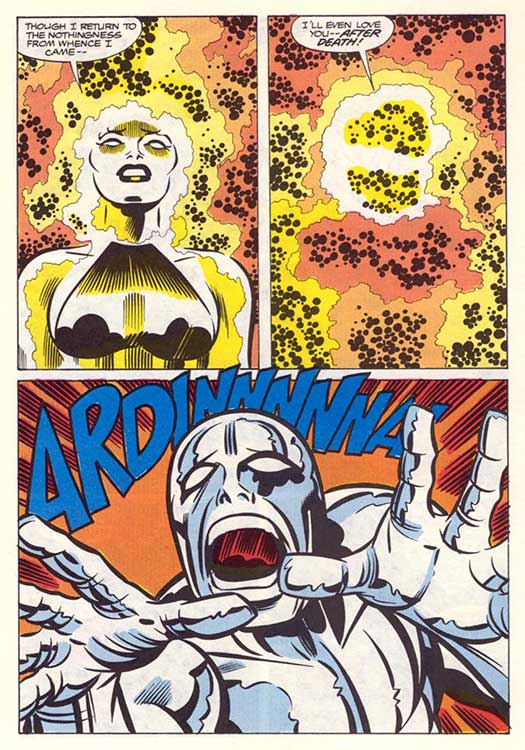

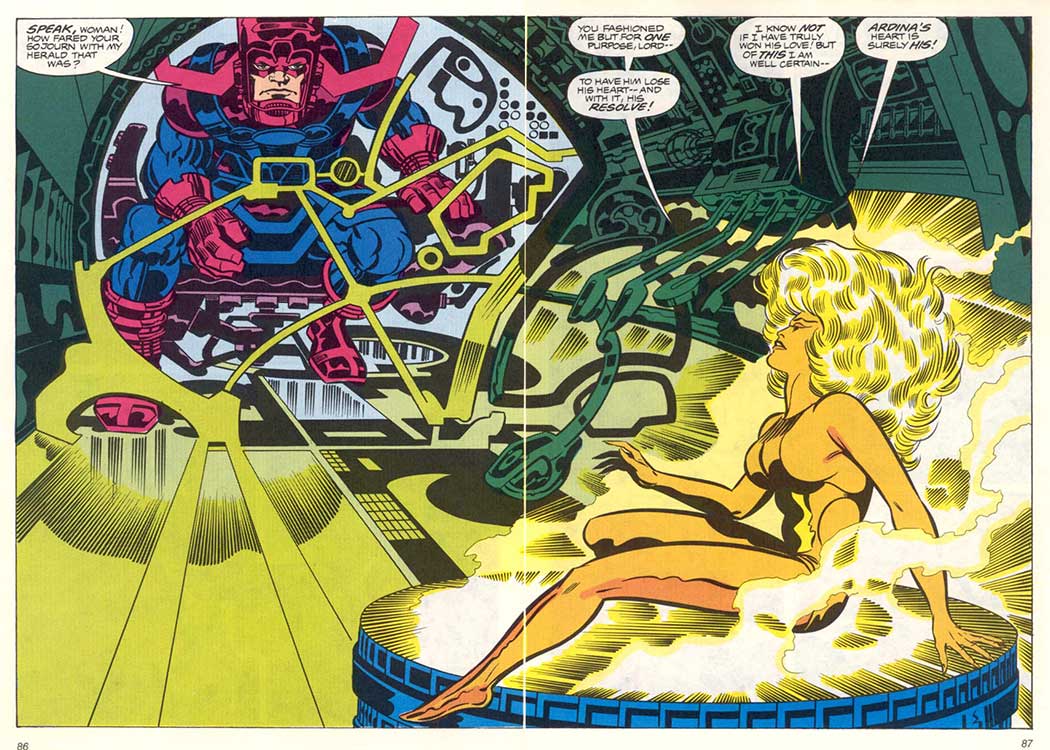

Behold! The hand of Jack Kirby! Behold! The hand of him who is like unto a god! Behold! The clutch of harnessed power — about to be released! Somewhere in the endless cosmos, the hand is opened! Somewhere in the swirling mists of space the power is unleashed! In the awesome vastness of infinity, in the panoply of a billion billion universes, where giant galaxies are ever born and ever dying, who will note the passing of a small and nameless planet? Behold! The hand of Jack Kirby!

(Selected panels from The Silver Surfer: The Ultimate Cosmic Experience, a 1978 prestige format one-off by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Absentmindedly pulled this off the shelf the other day and promptly lost my socks. Track this masterwork down, arguably Marvel’s first “graphic novel” and prepare to lose your socks, bub! — knocked clean off by the cosmic hand of Jack Kirby! Behold!)

Just virtually hanging this classic swatch of snotty amazingness on the virtual wall of my virtual blog. Virtually. Poster by Barney Bubbles the endlessly delightful design imp behind classic Hawkwind and Stiff Records. Check his monograph Reasons to Be Cheerful if you can score it.

While reading Charles Spencer’s lavishly illustrated biography of Leon Bakst and his design work for the Ballets Russes I came across his arresting manifesto for the vivid power of color. Looking at these intoxicating renderings and drawings the mind boggles at the lushness of the spectacle this must have been. Lush and lost. More on Bakst in an earlier post, here.

I have often noticed that in each colour of the prism there exists a gradation which sometimes expresses frankness and chastity, sometimes sensuality and even bestiality, sometimes pride, sometimes despair. This can be felt and given over to the public by the effect one makes of the various shadings.

That is what I tried to do in Schéhérazade. Against a lugubrious green I put a blue full of despair, paradoxical as it may seem. There are reds which are triumphal and there are reds which assassinate.There is a blue which can be the colour of a St. Madeleine, and there is a blue of a Messalina.

The painter who knows how to make use of this, the director of the orchestra who can with one movement of his baton put all this in motion, without crossing them, who can let flow the thousand tones from the end of his stick, without making a mistake, can draw from the spectator the exact emotion which he wants them to feel.

Omens. It’s hard not to look for omens these days. Last year began black, pulled through the vacuum of Bowie’s passing and slouched, heavy & low, towards November, when Leonard Cohen’s cloak crumpled to the Death Star floor.

But, as Leonard Nimoy reminds us, the cosmic ballet goes on, and this year began bright and blazing. Cherry Glazzer shot across the January sky like a crackling, wildly erratic comet. There are craftier salvos on the delightful Apocalipstick, sure, but “Trash People” is where it’s at — 19 year old Clementine Creevy’s neon ode to wearing old undies, fueled by Ramen, aiming for the stars. My room smelled like an ashtray once too.

Another portent of radness was Roky Erickson’s gobsmacking live performance this September — sitting in utter serenity like a psychedelic Totoro amidst a cyclone of sizzlin’ fuzz. He opened with the one song I dearly hoped to hear — “Sputnik” — a gift echoed in shows by Al Stewart, who kicked off his Year of the Cat retrospective with “Sirens of Titan” and King Crimson, who opened their stunning reprise of seldom heard 70’s material with a full dress parade of “Lark’s Tongue in Aspic” Old heads were generous this year, and fierce.

The glammy, psychotronic and exquisitely addled Death Valley Girls opened for Roky and were a total gas.

The continued activity by stalwart members of LA’s 80’s punk heyday continues to be a source of profound pleasure and surprise. TSOL and Dream Syndicate released tremendous records this year, both bracingly modern but rooted in beloved earlier classics like Beneath the Shadows and Days of Wine and Roses. Even by those lights, though, the new record by legendary LA paisley punks the Last is something else entirely — tearing, snarling, breathtakingly melodic, gorgeously arranged, Danger is a full-on, definitive SoCal punk rock classic. (It says something about the obscurity of this achievement that its existence eluded even this super-fan for almost four years; it says something about the stature of this achievement that the record cover is graced with art by Raymond Pettibon.)

I don’t know about you, but my goth fever shows no signs of breaking. This year I was in full swoon for the Sisters of Mercy — proudly 30 years late to this midnight movie. But clearly these dark currents still run deep — one of the most accomplished and moving records I heard this year was the Demonstration by LA’s enigmatic Drab Majesty. Sonically built from readymade darkwave parts, it is a triumph of bracing melodrama and strikingly original songs.

Ladytron’s Helen Marnie’s ongoing project to morph indie electronica into stadium scale dance pop continues to yield irresistible, shimmering, sexy concoctions.

Whiteout Conditions, The New Pornographer’s second exploration of the creative potential of the arrpegiated synthesizer was marred only by the absence of Dan Bejar’s leavening weirdness. With Destroyer’s “In The Morning” here following the stomping “Colosseum,” they are fittingly re-united.

One of the enduring joys of crate digging is stumbling across seminal bands that somehow eluded your attention. Take the masterful Chameleons, for example, who happened to be standing right next to the Psychedelic Furs, Modern English and Bauhaus this whole time.

But then the obscurities can be pretty fucking exhilarating too — like encountering “Worlds in Collision” by Talking Head bassist and ex-Modern Lover Jerry Harrison. A needle in a haystack find, this throbbing, hypnotic rumble was a beautiful oddity I returned to over and over this year.

Un autocollant sur la couverture du premier album éponyme des Limiñanas en 2010 disait: “Nouvelle musique pop française pour le prochain millénaire”. La pop classique parisienne, la psychologie californienne, le garage / surf rock, Serge Gainsbourg et Ennio Morricone étaient alors les points de référence, et ils le restent sur Malamore. C’est une pièce d’ambiance – haut sur la répétition, fuzz et sitar – et leur plus sombre, plus dense pourtant, qui sonnent bien plus Velvet Underground & Nico que Françoise Hardy.

Total time: 51 minutes. Download the comp here.

[ ALSO, below: I finally re-created and re-posted the first in this series from 2008. It was a corker of a year for music and the mix remains one of my favorites. Check it out here! ]

Mr. Rossetti has been known for many years as a painter of exceptional powers, who, for reasons best known to himself, has shrunk from publicly exhibiting his pictures, and from allowing anything like a popular estimate to be formed of their qualities. He belongs, or is said to belong, to the so—called Pre~Raphaelite school, a school which is generally considered to exhibit much genius for colour, and great indifference to perspective. It would be unfair to judge the painter by the glimpses we have had of his works, or by the photographs which are sold of the principal paintings judged by the photographs, he is an artist who conceives unpleasantly, and draws ill.

Like Mr. Simeon Solomon, however, with whom he seems to have many points in common, he is distinctively a colourist, and of his capabilities in colour we cannot speak, though we should guess that they are great; for if there is any good quality by which his poems are specially marked, it is a great sensitiveness to hues and tints as conveyed in poetic epithet. These qualities, which impress the casual spectator of the photographs from his pictures, are to be found abundantly among his verses.

There is the same thinness and transparence of design, the same combination of the simple and the grotesque, the same morbid deviation from healthy forms of life, the same sense of weary, wasting, yet exquisite sensuality; nothing virile, nothing tender, nothing completely sane; a superfluity of extreme sensibility, of delight in beautiful forms, hues, and tints, and a deep seated indifference to all agitating forces and agencies, all tumultuous griefs and sorrows, all the thunderous stress of life, and all the straining storm of speculation.

Mr. Morris is often pure, fresh, and wholesome as his own great model; Mr, Swinburne startles us more than once by some fine flash of insight; but the mind of Mr. Rossetti is like a glassy mere, broken only by the dive of some water—bird or the hum of winged insects, and brooded over by an atmosphere of insufferable closeness, with a light blue sky above it, sultry depths mirrored within it, and a surface so thickly sown with water~lilies that it retains its glassy smoothness even in the strongest wind. Judged relatively to his poetic associates, Mr. Rossetti must be pronounced inferior to either. He cannot tell a pleasant story like Mr. Morris, nor forge alliterative thunderbolts like Mr. Swinburne. It must be conceded, nevertheless, that he is neither so glibly imitative as the one, nor so transcendentally superficial as the other.

We at once recognize as his own property such passages as this:

I looked up

And saw where a brown—shouldered harlot leaned

Half-through a tavern window thick with vine.

Some man had come behind her in the room

And caught her by her arms, and she had turned

With that coarse empty laugh on him, as now

He munched her neck with kisses, while the vine

crawled in her back.Or this: —

As I stooped, her own lips rising there

Bubbled with brimming kisses at my mouth.Or this: —

Have seen your lifted silken skirt

Advertise dainties through the dirt!Or this: —

What more prize than love to impel thee,

Grip and lip my limbs as I tell thee!Passages like these are the common stock of the walking gentlemen of the fleshly school. We cannot forbear expressing our wonder, by the way, at the kind of women whom it seems the unhappy lot of these gentlemen to encounter. We have lived as long in the world as they have, but never yet came across persons of the other sex who conduct themselves in the manner described. Females who bite, scratch, scream, bubble, munch, sweat. writhe, twist, wriggle, foam, and in a general way slaver over their lovers, must surely possess some extraordinary qualities to counteract their otherwise most offensive mode of conducting themselves. It appears, however, on examination, that their poet—lovers conduct themselves in a similar manner. They, too, bite, scratch, scream, bubble, munch, sweat, writhe, twist, wriggle, foam, and slaver, in a style frightful to hear of. Let us hope that it is only their fun, and that they don’t mean half they say. At times, in reading such books as this, one cannot help wishing that things had remained for ever in the asexual state described in Mr. Darwin‘s great chapter on Palingenesis. We get very weary of this protracted hankering after a person of the other sex; it seems meat, drink, thought, sinew, religion for the fleshy school.

Robert Williams Buchanan onDante Gabriel Rossetti

Contemporary Review, October 1871.