> DOWNLOAD THE COMP HERE

> DOWNLOAD THE COMP HERE

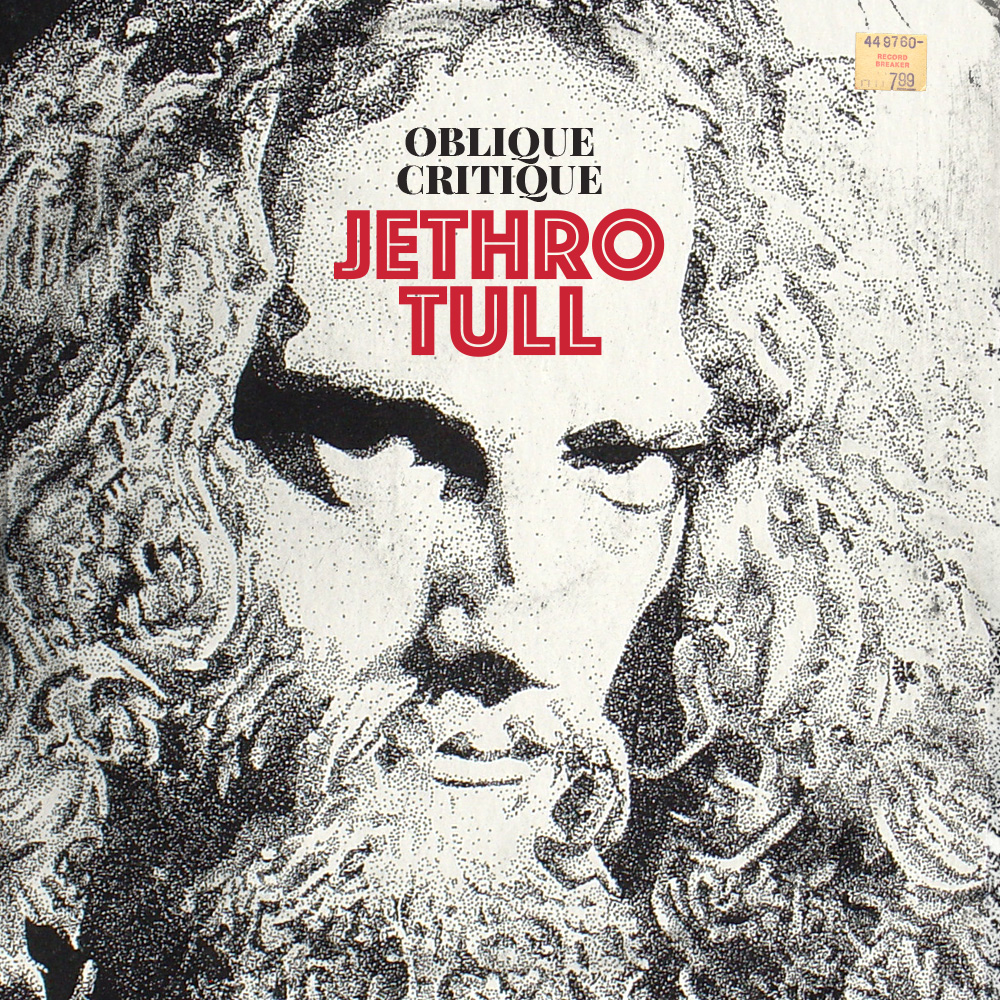

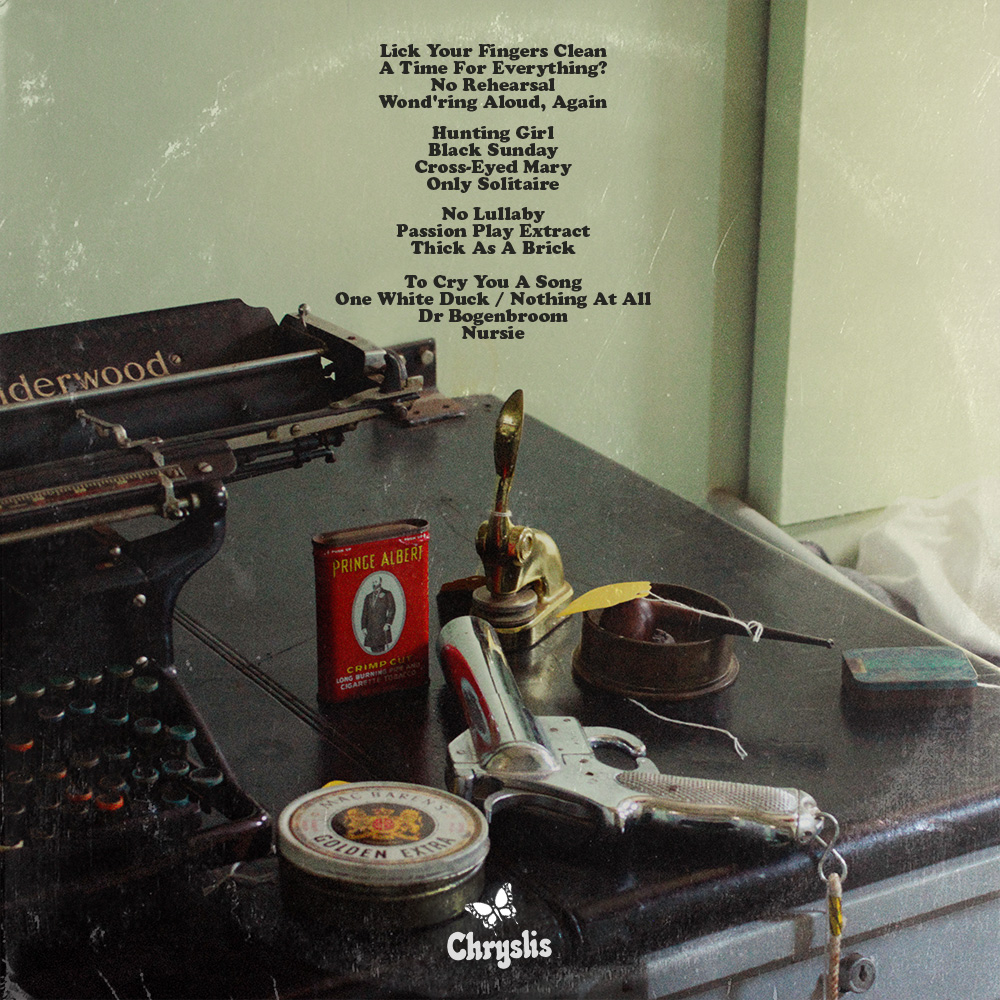

Jethro Tull has been, consistently and ardently, my favorite band for the last 30 years.

Wherever and however far I might drift — across oceans of punk, pop, prog & psychedelia, into sunken caves of dub or swampy lagoons of goth, down pulsing Krautrock channels, upended by typhoons of metal — I always tie back up with Tull.1

My conversion experience occurred in profoundly improbable circumstances. In 1988 I was in high school, peaking with hardcore punk rock fever. Amongst our rag-tag handful of like-minded misfits, Suffer, a new album by Bad Religion (back then a far lesser known band) was gathering some serious killer buzz. Finally, one kid scored it from an older brother and brought it in for me to gym class. I promptly inserted the home recorded tape into my AIWA walkman.

Now, if you recall, the key feature of mid-period Walkmen was “auto reverse” functionality allowing you to play either side of the tape without physically reversing the cassette. Pressing play, then, I entered a singular, un-repeatable fantasia where basically, for about maybe 15 seconds, I thought some random snippet of what turned out to be Jethro Tull was the new Bad Religion. And fucking loving it. A little perplexing, surely, but yea, fucking loving it. Soon enough I regained my bearings and flipped over to the other side, promptly losing myself in the masterwork that was Suffer.2

But in those disorienting seconds the sonic allure of Jethro Tull took hold. Then and there, I managed to grok a concentrated dose of their jam — those sizzling, off-kilter riffs, improbable melodies, all cinched up tight by the singular rough velvet timbre of Ian Anderson’s voice. And the whole flute thing. So, even as I remained the doctrinaire punk, the spell and the die were cast.3

My enthusiasm for Tull has often struck others as a bit incongruous, given my other musical pleasures and predilections. Over the years, one cat or another has asked me to put together a representative mix of their tunes. While these requests are rooted, I’m sure, in genuine open curiosity, I always detect a flash of a skeptical edge, a pointed demand to justify Tull’s place in my celestial hierarchy. So, in recognition of their 50th year, and my three decades of devoted fan-hood, it feels like high time I take my own measure of their radness.

On Jethro Tull’s “greatest hits” there is a mighty and widely shared consensus. The songs collected on the 1976 best-of LP’s M.U. The Best of Jethro Tull, with the exception of one fan-rewarding rarity, are canonical, enduring FM rock radio staples. However Tull’s stature as classic rock powerhouse draws selectively from a deeply weird, idiosyncratic body of work.4

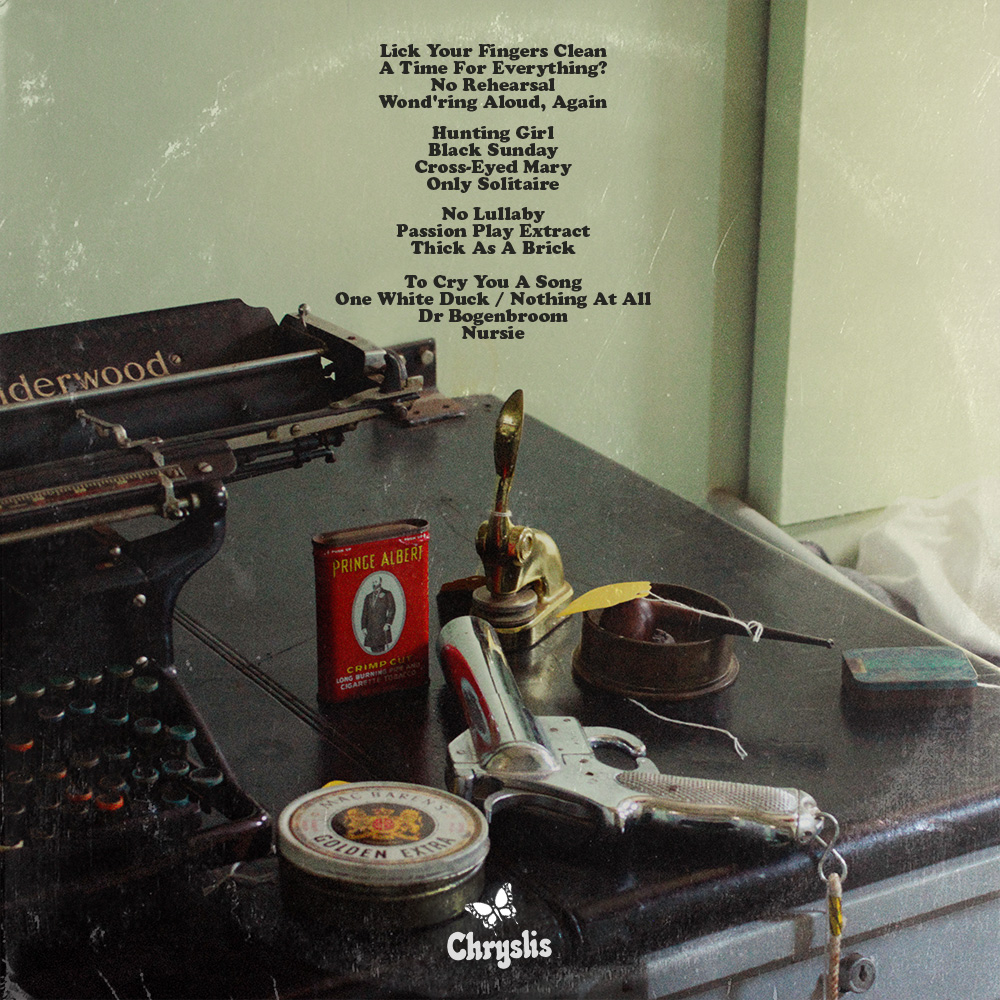

This particular selection of tunes, first and foremost, is my own rendering of Jethro Tull’s singular sensibility — drawing at times on key rarities, alternate recordings, live performances, and deep album cuts. This is not showboating fan service or willful obscurantism. Rather, it is an effort to make a a broader case for Tull as an absolutely killer psychedelic rock band of particular interest to those inclined (like the reputation enjoyed, let’s say, by Van Der Graf Generator). All the songs are in some way fundamental to the band’s identity, while also being top-grade left-of-the-dial rock and roll.

For me Jethro Tull’s classic period is comprised of four rather distinct phases which flow and feather into one other at the edges.5 By around 1969 Anderson had established nearly complete aesthetic control of the band. He was still working within and inside recognized rock forms, but songs were beginning to be yanked into distinctive shapes (A Time For Everything?, To Cry You A Song, Dr Bogenbroom) or stretched out into ambitious suites (Wondering Aloud, Again). All the while, though, riffs remained the anchor and engine of the songs.6

With 1971’s Aqualung, Anderson’s titanic talent, personal passions and quirks (and, frankly, ego) had utterly subsumed the band. Here begin his alchemical experiments with various ratios of rock, English folk, classical, and Elizabethan music. Lyrically he also sets off alone for parts unknown, with his mix of religious allegory, detailed character sketches, verbal dexterity, general inscrutability, and no small dose of Python-esque humor. This era simultaneously produced their biggest popular successes, fiercest critical drubbings, and acres of stunning, exhilarating and challenging music (Cross-Eyed Mary,7 Lick Your Fingers Clean, No Rehearsal)

Around this time Tull had also cemented its reputation as a crushingly stellar live act (No Lullaby, Passion Play Extract, Thick As A Brick). Impeccable, muscular musicianship, rollercoaster set-lists, all wildly energized by Anderson’s legendary showmanship – a galvanizing, whirling, one-footed, flute brandishing, cod-pieced dervish.

Tull’s massive sales and live success had the additional benefit of inoculating the band, and especially Anderson, against any permanent scarring from what was a turbulent and tumultuous period of peak fame, popularity and exposure. By the mid 70’s Anderson was purposely withdrawing from the show-biz hullaballoo, spending more and more time in various countrysides. In 1978 he bought and moved to an estate out by the Outer Hebrides in remote Scotland. A growing interest in folklore, fantasy tales and British rural traditions began to profoundly shape Anderson’s writing (Hunting Girl). This rural sensibility culminated in a trilogy of folk rock records with which Tull closed out the decade.

This period, much beloved by fans, was memorialized by the double LP live album Bursting Out and came to an abrupt and tragic end with the death in 1979 of Tull’s bassist John Glascock. Disbanding the band indefinitely, Anderson began work on a solo record which reflected his bourgeoning interest in synthesizers.

Anderson’s label Chrysalis insisted that the record be credited to the band, thus forcibly inaugurating Jethro Tull’s quirky electronic folk era. Although it yielded some choice sides (Black Sunday) and arguably led to one last classic album, 1982’s Broadsword and the Beast,8 this new tack remained divisive among fans, critically thrashed, and profoundly out of sync with general audiences. Anderson mined this sound for one more record with rapidly diminishing returns.9

Meanwhile, all along, weaving and braiding through these wild knotty morphings was Anderson’s steady, almost devotional, composition of exquisite acoustic guitar songs (Only Solitaire, One White Duck / Nothing At All, Nursie). Regularly deployed on every album, taken together they comprise an alternate songbook of consistently remarkable beauty and craft.

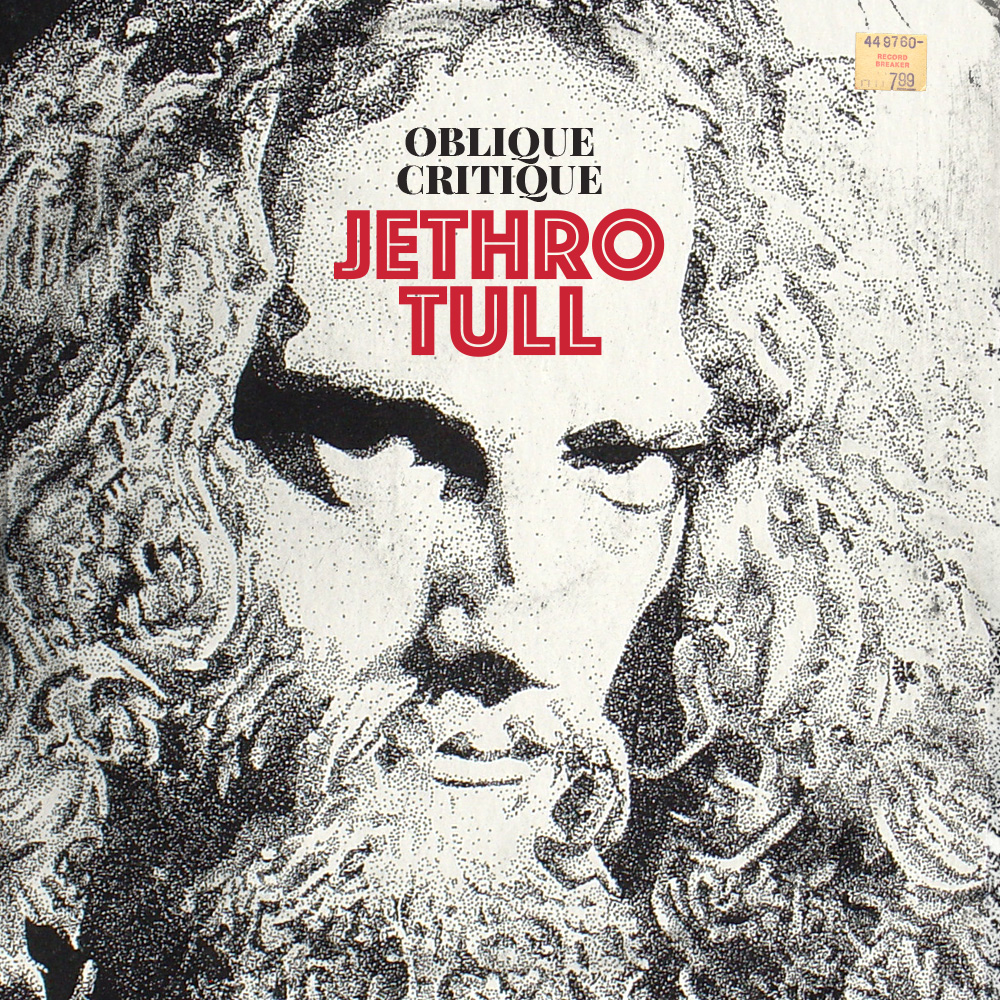

The title Oblique Critique is a reversal of “Critique Oblique,” the title of a segment of 1972’s single song-length record A Passion Play. Besides being an apt title, it’s fitting that it’s taken from a record that is nothing less than Tull apotheosis – Majestic, exhilarating, wildly ambitious, overthought, dead serious, ostentatiously clever, in patches profoundly silly, passionately beloved by fans (except by those that passionately dislike it), reviled by the rock “intelligencia,” and utterly impenetrable to the uninitiated. And of course, stateside, it went to #1 on the charts.

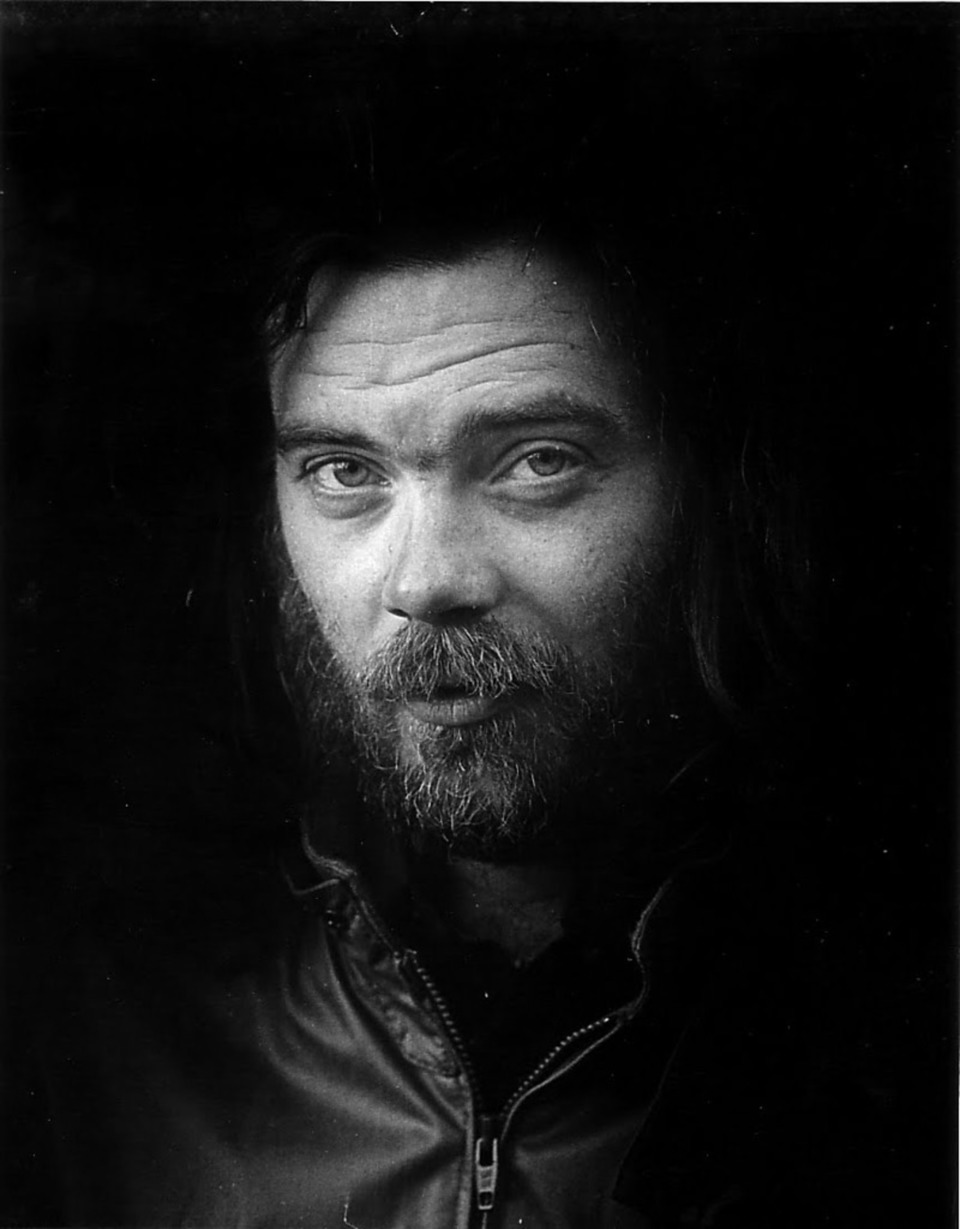

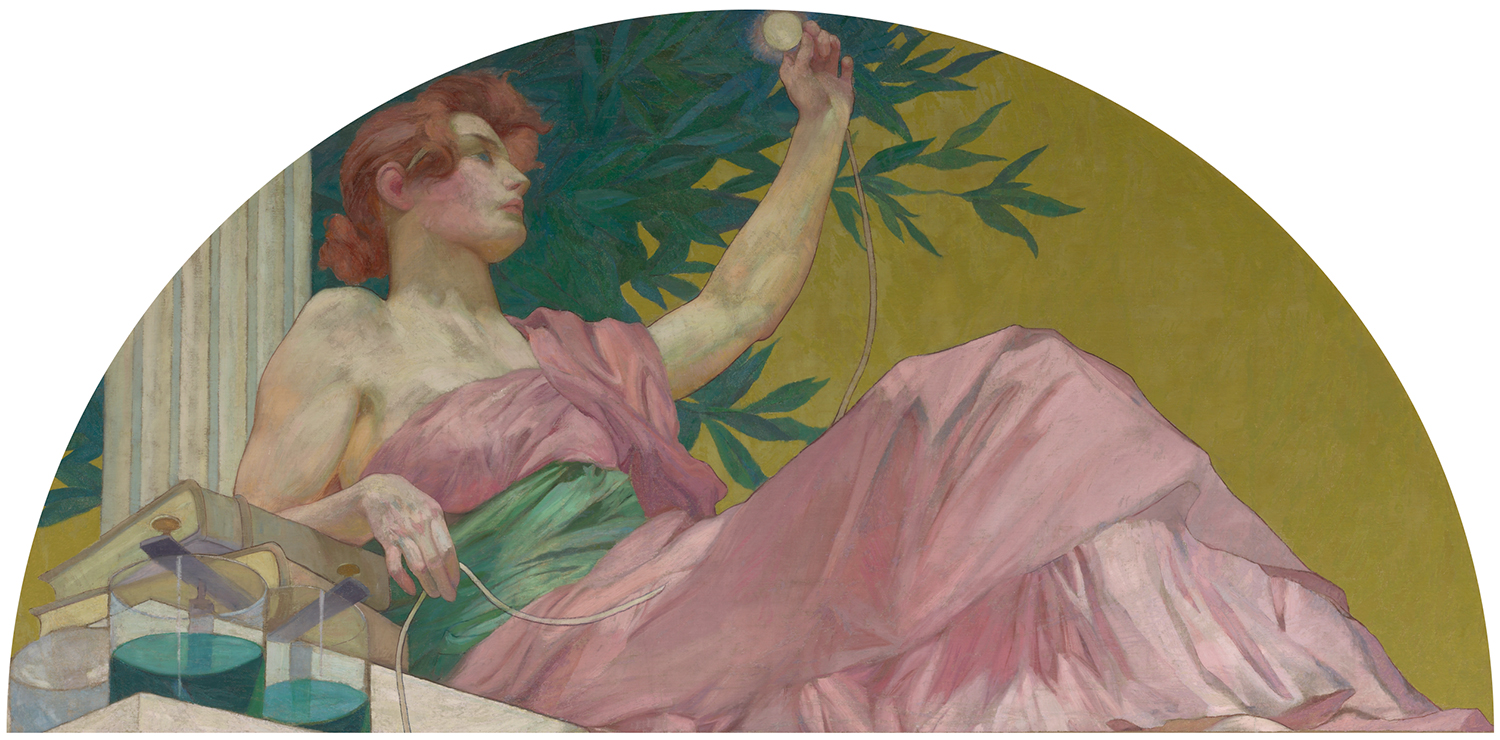

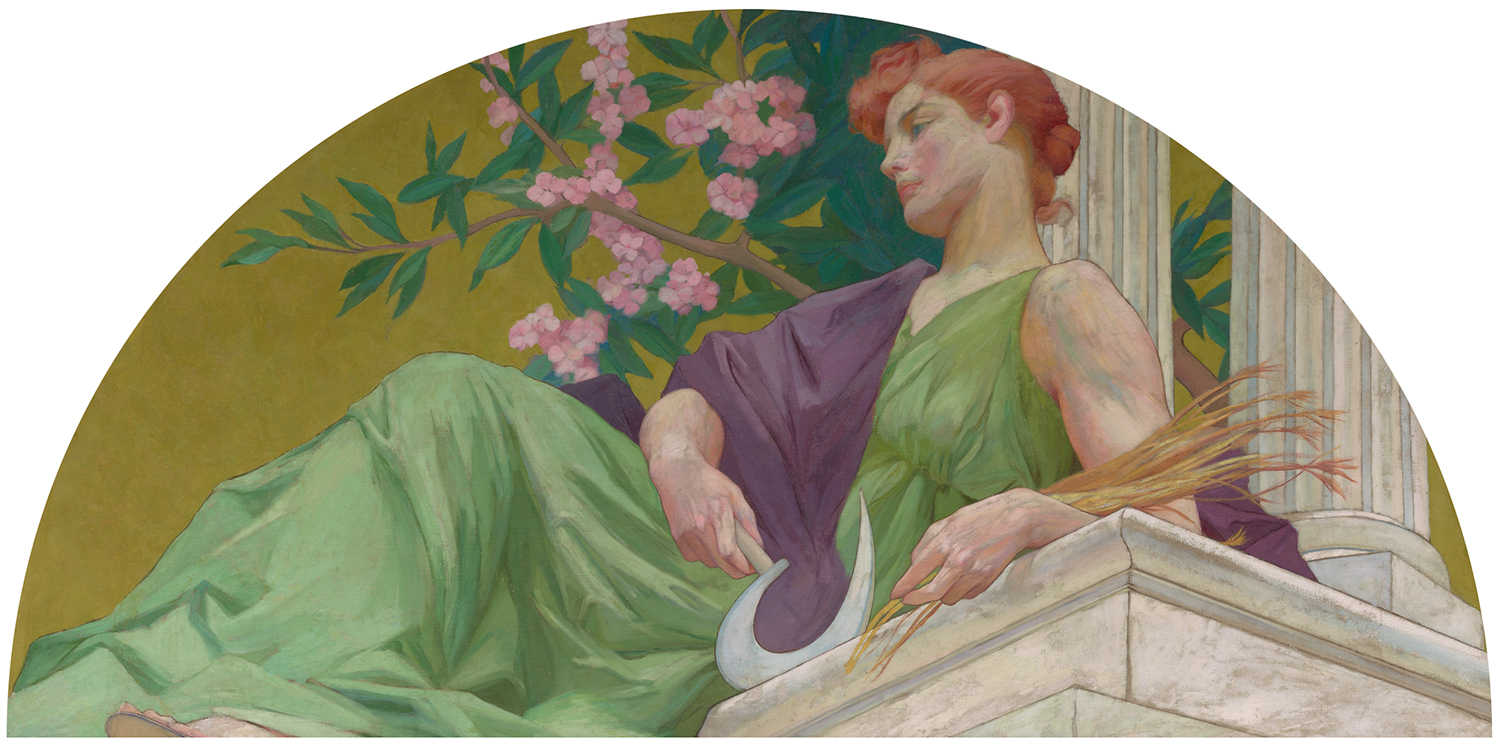

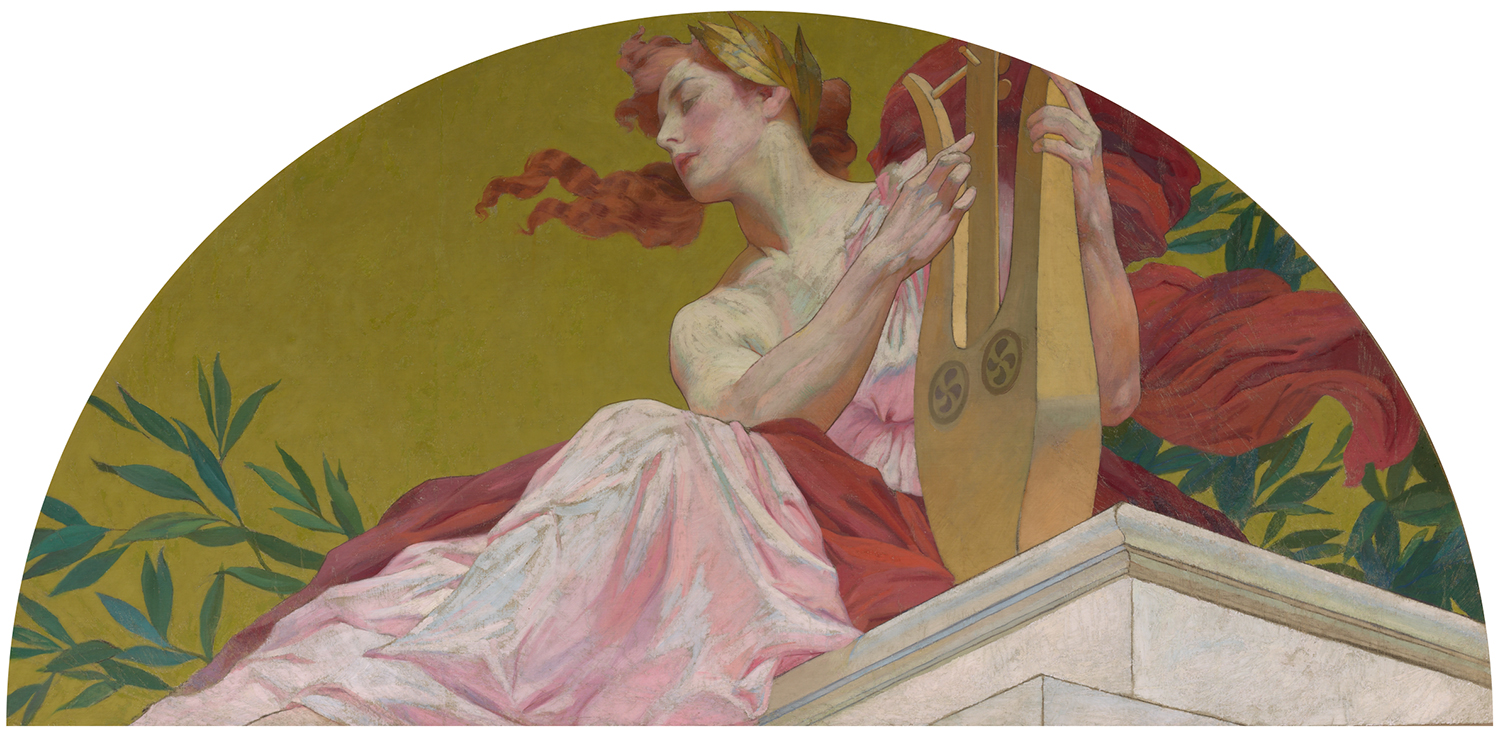

Front cover art by Rebecca Caviness

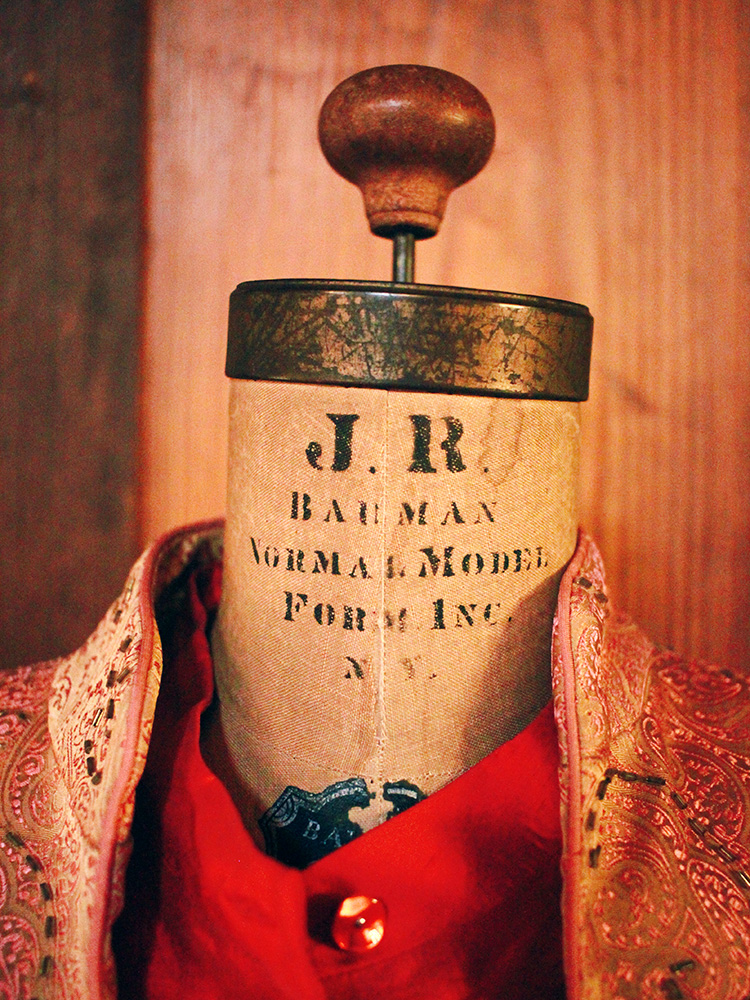

Back cover photo by Dan Shepelavy

> DOWNLOAD THE COMP HERE

Some notes, for those inclined…

1 An island which I imagine to be very much like the the actual Scottish island of Skye, home to the Strathaird Estate which Tull’s Ian Anderson bought and moved to in 1978. Scottish mountaineer William Hutchison Murray described the island as “sixty miles long, but what might be its breadth is beyond the ingenuity of man to state.” There Anderson began his storied adventures in commercial salmon fishing. I always imaged its verdant rolling lands to be patrolled by colonies of Anderson’s beloved Bengal cats — a totally bad-ass domestic house cat developed to look like leopards or tigers.

2 thereby establishing my second favorite band of all time – Bad Religion. The Jethro Tull/Bad Religion connection gets even more uncanny. Prior to Suffer, Bad Religion had released its infamous sophomore LP, Into the Unknown. In bewildering contrast to their rough hardcore debut the new record was a reverb drenched, organ swirled, heady psych record that had, as some critics pointed out, more in common with Hawkwind than any known punk reference points (If that sounds pretty amazing it’s because it is. Into the Unknown is an ace record.) It caused a mighty kerfuffle, helped precipitate the bands’ breakup, and was largely disowned after it’s release and hostile reception. In an later interview Bad Religion’s singer Greg Graffin explained that while he was still immersed in the hardcore scene he had developed an powerful affection for Tull and felt compelled to write a set of like-minded songs. He felt it was the most punk rock thing he could do.

3 1988 was a pretty exciting time to have been introduced to Tull. The year prior had seen the release of Crest of A Knave, seen as something of a comeback after 1984’s listless Under Wraps. Knave’s lead single, the (honestly) atrocious “Steel Monkey,” famously and improbably won the inaugural Heavy Metal Grammy award that year, beating out the third band in my high school era holy trinity: Metallica)

Crest of A Knave was also the first record made after Anderson’s battle with a significant throat infection that permanently cleaved off the upper registers of his voice. Although he has gamely and often deftly adjusted his new material and live arrangements to compensate, the music has dimmed overall a bit as a result.

What was seismic in 1988 was the release of the massive 5LP box set 20 Years of Jethro Tull. One of the best fan-focused box sets ever released it featured over four hours of largely unreleased material. Fragments of legendarily scrapped albums, enough rare B-sides to turn their parent records into double LP’s, revelatory studio outtakes and alternate versions — with one stroke it presented a massive and fascinating expansion of Tull’s classic oeuvre.

4 A dynamic they share with, for example, Roxy Music, who’s silky hits can be defiantly at odds with their prickly and at times aggressively odd catalog. This is in contrast, I’d argue, with other prog/glam/AOR/stadium superstars like Pink Floyd, the Who, or Yes where the “hits” and the rest of the oeuvre are much more of a piece. Incidentally, Roxy opened for Tull on their 1972 tour – with both bands at the apex of their powers it must have been astonishing.

5 I have a generally strong allergy to the blues, and as a result don’t really much rate or personally enjoy the first two Tull studio LPs. However, for blues-inclined listeners they have much to offer, not the least of which is tracking Anderson’s take on and emergence from the form. And Anderson clearly considers it a legit component of their overall legacy as he has occasionally returned to this period live.

6 In his review of 1970’s Benefit, critic Robert Christgau, by no measure a fan of the band (“I find [their] success very depressing”) allowed that Anderson “does have one undeniable gift, though — he knows how to deploy riffs.”

7 There exists an endearing bonhomie between the classic British metal scene and Tull. In 1968 Sabbath’s Tony Iommi did a split second stint as a Tull member, and remained a pal and supporter ever since. Anderson and Lemmy were longstanding and unlikely chums (Anderson titled a superb recently discovered outtake from Songs From the Wood “Old Aces Die Hard” in tribute to Lemmy.) Iron Maiden, particularity, are massive Tull fans. Their barnstorming cover of “Crosseyed Mary” is a glorious toast and fond tribute — and for me, the singular instance of a Tull cover worth listening to.

8 In putting together this compilation I was surprised that Broadsword and the Beast, an album I adore, stubbornly resisted representation. It is a tremendously entertaining record, especially in its expanded nearly double LP form, with many personal favorites (“The Clasp,” “Pussy Willow,” “Jack Frost and the Hooded Crow,” “Down At the End of Your Road”) But the songs withered and wobbled when taken out of context. Ultimately I think Broadsword is a particularly insular record, and one that makes sense only within the context of deep fandom. It is also a profoundly geeky album, with a heavy D&D vibe that may be for converts only.

9 In retrospect the run of albums 1988’s Crest of a Knave inaugurated are, under even the most charitable lights, a spotty patch. The muse stirred a bit on two largely acoustic solo records in the early ‘aughts. However, the real “comeback” would have to wait until 2012 when Anderson, now operating solo, unexpectedly released a “sequel” to 1972’s Thick as a Brick.

The only thing more absurd than the idea of a sequel to this famously obtuse prog-rock masterpiece is how decent it actually is. Anderson had assembled a virtuoso band that scrupulously recreated the distinctive sonics of 70’s era Tull and he delivered a set of songs to suit. This led in short order to Anderson’s definitive late career triumph Homo Erraticus, another sprawling throwback prog epic, this time wholly original in topics, themes and tunes. Highly recommended.

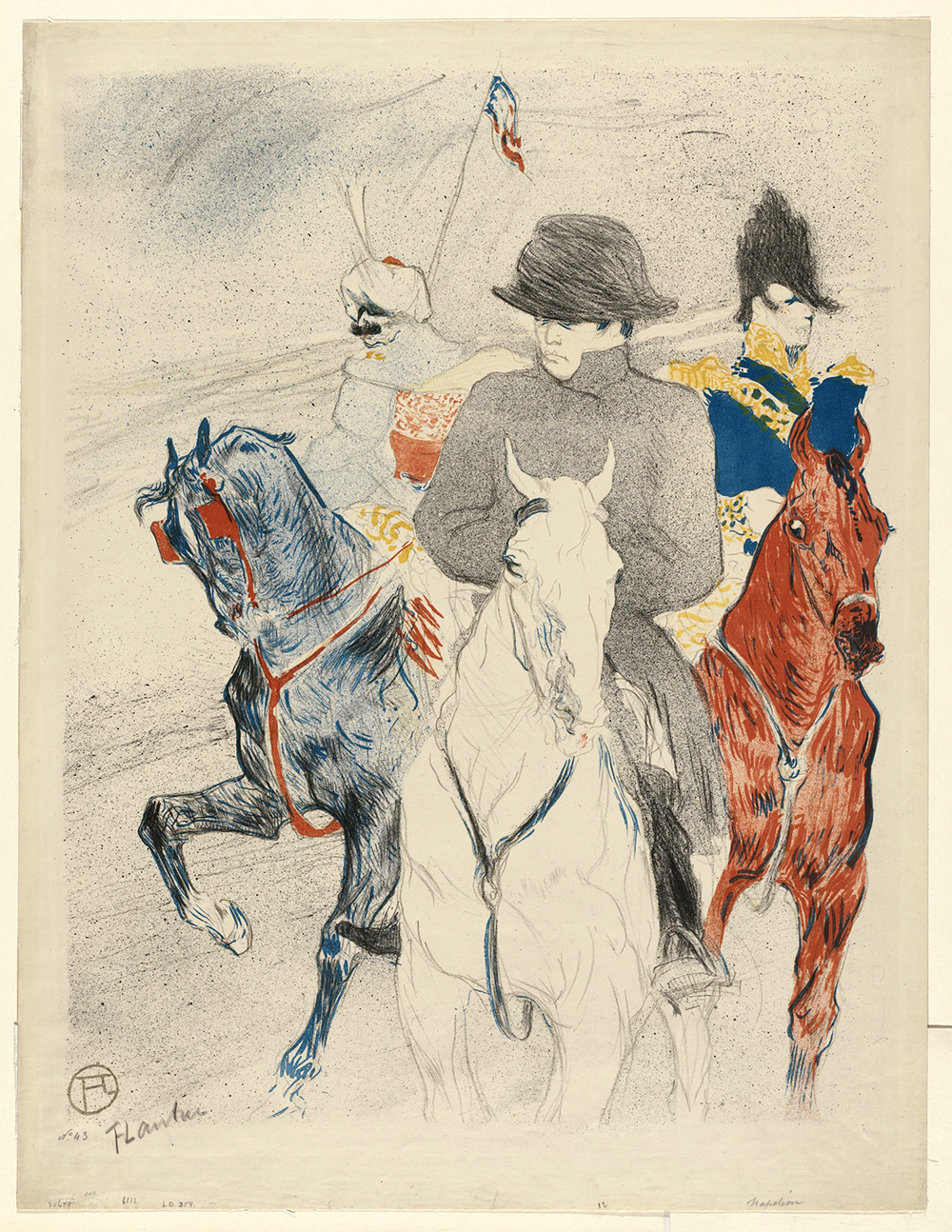

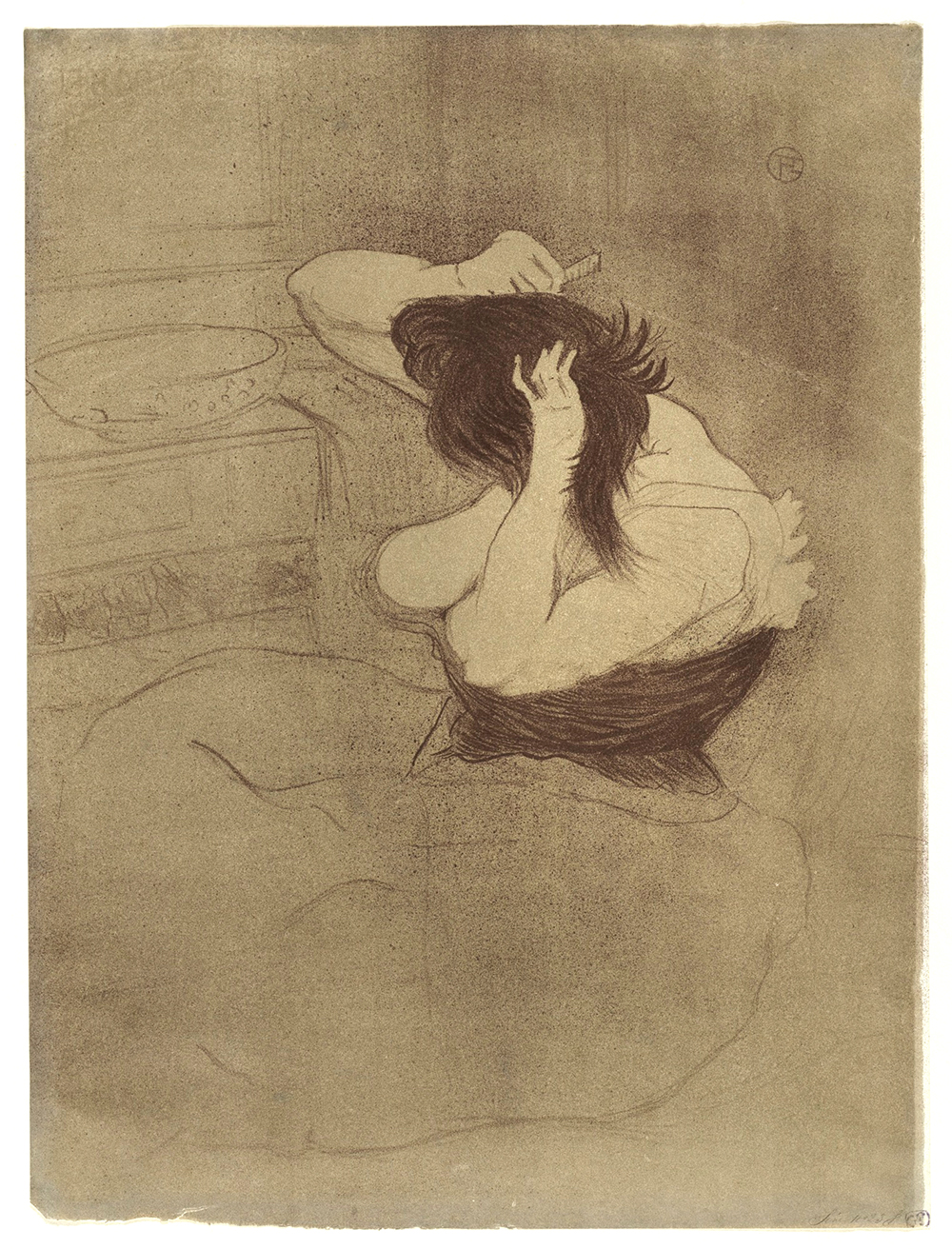

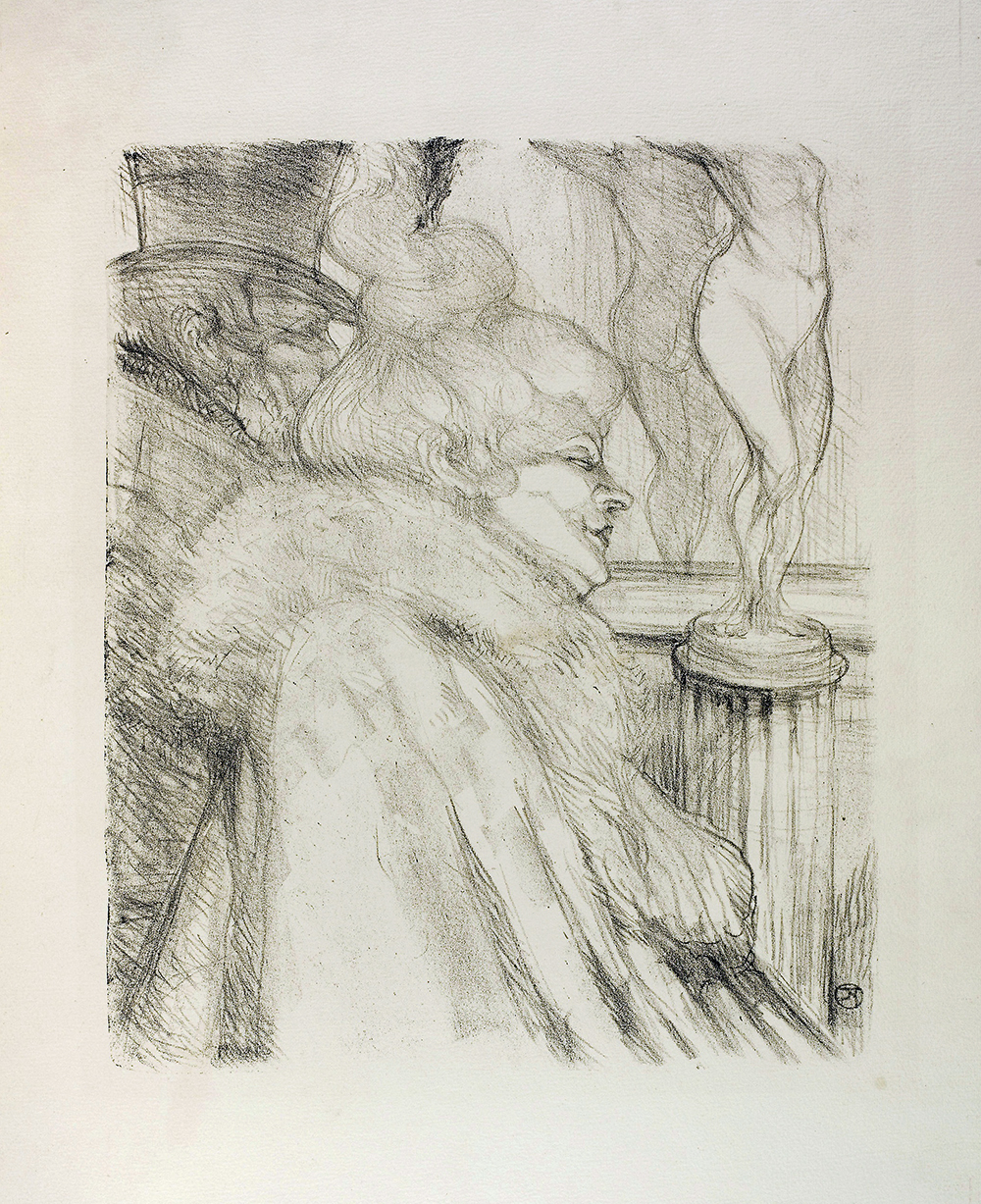

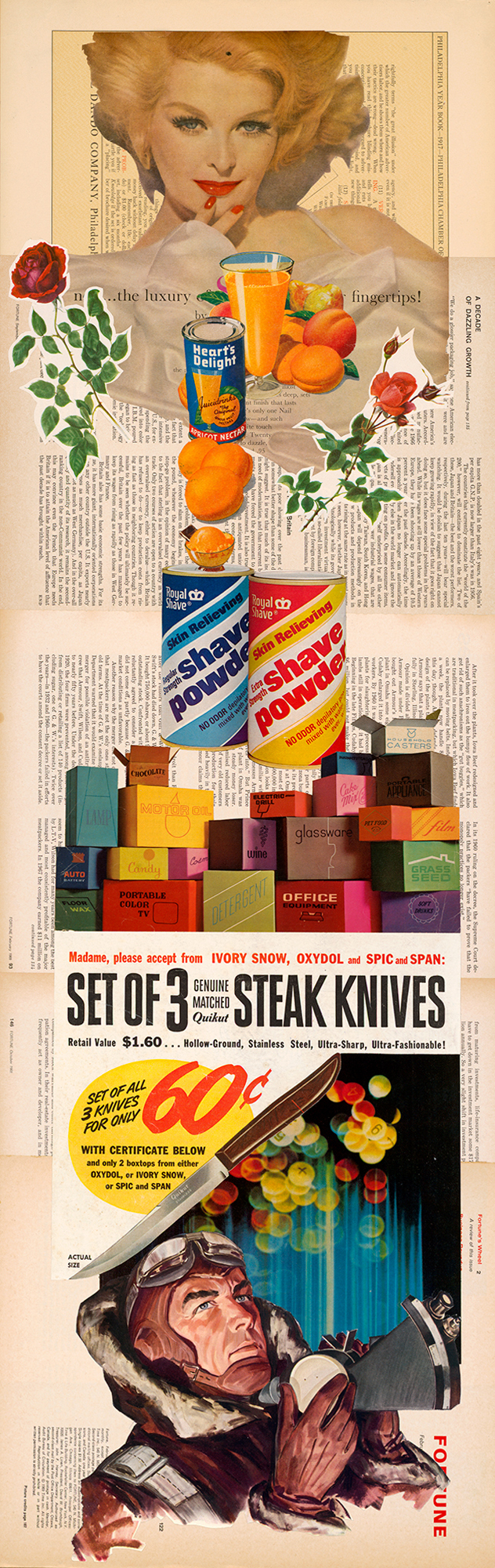

Last year I had the distinct pleasure of making these collages for the interior of HomeMakers Bar in Cincinnati. Each collage spotlights a different era – 50’s, 60’s, 70s, playfully subverting the traditional iconography of homemaking, cocktail culture, and swank entertaining. In the words of their inspired founders Julia Petiprin, Catherine Manabat, HomeMakers Bar is “a slightly retro, mostly modern cocktail bar that feels like a house party.” While I can only admire the delightful food and drink offerings virtually, I can say that the space and decor is a showstopper. It is, I think, hard to pull of something fresh in a “retro” mode and HomeMakers Bar has clearly emerged as a singular creative and culinary statement that easily transcends its original inspirations. (More interior images can be found on the portfolio page, here.)

Last year I had the distinct pleasure of making these collages for the interior of HomeMakers Bar in Cincinnati. Each collage spotlights a different era – 50’s, 60’s, 70s, playfully subverting the traditional iconography of homemaking, cocktail culture, and swank entertaining. In the words of their inspired founders Julia Petiprin, Catherine Manabat, HomeMakers Bar is “a slightly retro, mostly modern cocktail bar that feels like a house party.” While I can only admire the delightful food and drink offerings virtually, I can say that the space and decor is a showstopper. It is, I think, hard to pull of something fresh in a “retro” mode and HomeMakers Bar has clearly emerged as a singular creative and culinary statement that easily transcends its original inspirations. (More interior images can be found on the portfolio page, here.)